Projects like DMIC propelled by SPV model may have the potential not only for funds mismanagement but also to create land speculation and social conflicts.

The infrastructure sector has been presented to be a key driver for the Indian economy. Responsible for propelling India’s overall development, the sector enjoys intense focus from the government as well as international financial institutions, bilateral agencies and private investors for initiating policies that would ensure time bound creation of world class infrastructure in the country. It would also boost manufacturing, employment generation and higher economic growth rates.

Some of the major infrastructure projects in the country comprise industrial corridors, smart cities including urban infrastructure such as water and sewerage systems, transport, metro systems, solid waste management, traffic management, digital infrastructure and urban housing. These are closely linked with national projects for power generation and transmission, roads and highways called Bharatmala Pariyojana, shipping and port modernisation, and coastal industrialisation projects named Sagarmala Programme, power and energy projects, civil aviation, logistics sector and housing for all.

In 2018-19 financial year, the Government of India had allocated Rs.5.97 lakh crore (USD 92.22 billion) to provide a massive boost to the infrastructure sector. This included allocations to railways, household level electrification scheme, green energy corridor, telecom infrastructure, metro rail systems, highway projects, among others. Similar announcements have been made in 2019-20 financial year with an allocation of Rs.4.56 lakh crore (USD 63.20 billion) for the sector. Rs.38,637.46 crore (USD 5.36 billion) have been allotted to communication and Rs.83,015.97 (USD 11.51 billion) towards road transport and highway, and investments in piped water supply to be provided to all households in 500 cities[1].

For mega infrastructure programmes like industrial corridors and Smart Cities Mission, it has been further emphasised that the need of the hour is to fill the infrastructure investment gap by financing from private investment – institutions dedicated for infrastructure financing like National Infrastructure Investment Bank (NIIB) and also global institutions like Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and New Development Bank (erstwhile BRICS Bank), focused more on sustainable development projects and infrastructure projects[2]. Various public financing options and marker based mechanisms have been proposed to raise finances for infrastructure projects.

Industrial corridors in India

An industrial corridor is generally defined as a set of linear projects designed for an area to promote infrastructure and industrial development. Its broad objectives include creating areas for urban, manufacturing or other industry clusters. Industrial corridors are planned in such a way that there are arterial links like a highway or railway line that receives feeder roads or railway tracks.

The Government of India has envisaged five industrial and economic corridors: Delhi-Mumbai Industrial Corridor (DMIC), Bengaluru-Mumbai Economic Corridor (BMEC), Chennai-Bengaluru Industrial Corridor (CBIC), Amritsar-Kolkata Industrial Corridor (AKIC) and Visakhapatnam-Chennai Industrial Corridor (VCIC), which is a part of the longer East Coast Economic Corridor (ECEC).

Delhi-Mumbai Industrial Corridor (DMIC)

DMIC has been envisaged as one of the largest infrastructure projects being implemented in India, along with Smart Cities Mission, Bharatmala and Sagarmala – both in financial as well as geographical terms. The project is expected to transform India into a global manufacturing and logistics hub with planned urban centres and manufacturing facilities. The initial financing for DMIC is estimated to be around USD 100 billion and, geographically, it would have influence areas spread across six states in the country, alongside a freight corridor including projects such as investment regions, industrial areas, logistics hubs, airports and urban centres. Each state has a nodal agency to coordinate the project implementation under DMIC. Special purpose vehicles (SPVs), which are limited liability companies under the Companies Act, 2013, have been formed at different levels to implement the plans through public private partnership (PPP) projects. Though initial financing for DMIC has come from the public sources, it is expected that a majority of it – around USD 90 billion – would come from private investors in the form of share capital, equity investment as well as through sale of land parcels. The other source of funds would be through PPP projects as well as investments by development finance institutions like the World Bank, Asian Development Bank (ADB) and others.

However, there are critical concerns that appear to not having been addressed, while proposing these lofty plans. They include the impacts of large scale land acquisition on local communities and their agriculture based livelihoods, resulting in displacement and violation of their resettlement rights, loss of ecological spaces and stress on water resources. Decision-making processes, wider public consultations and considering the opinions shared, role of people’s representatives and local governments as well as the increased push for profit making for domestic and international investors are other vital concerns left unaddressed.

In 2007, DMIC was announced as the first industrial corridor project in the country by the Government of India. The project was launched after an agreement was signed between the Government of India and the Government of Japan in 2006. The Delhi Mumbai Industrial Corridor Development Corporation (DMICDC) was formed in 2008 for developing and implementing the project.

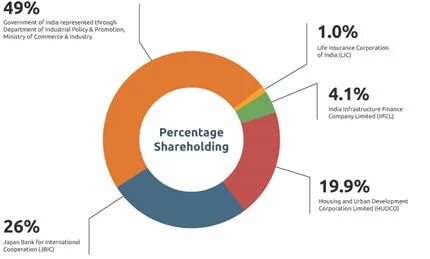

The equity shareholders in the company are Government of India (49 per cent), through the Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion (DIPP), Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC) (26 per cent) and financial institutions such as Housing and Urban Development Corporation (HUDCO) (19.9 per cent), India Infrastructure Finance Company Limited (IIFCL) (4.1 per cent) and Life Insurance Corporation (LIC) (1.0 per cent).[3]

The Government of Japan had also announced financial support for the project for an amount of USD 4.5 billion in the first phase for the projects with Japanese participation.[4]

The project influence area run through six states – Uttar Pradesh, Haryana, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat and Maharashtra. The project runs along the Western Dedicated Freight Corridor (WDFC) of the railways and looks to utilise the high speed and capacity connectivity provided by DFC to reduce logistics costs.[5] A strip of 150 km to 200 km has been selected on both the sides of WDFC to be developed as industrial corridor. It would also develop feeder rail/ road connectivity to hinterland/ markets and select ports along the western coast.[6]

As part of the implementation work under DMIC, 24 special investment nodes – 13 investment areas and 11 investment regions – have been identified under the project across the six project states. An investment region would have a minimum area of over 200 square kilometres (20,000 hectares), while an industrial area would have a minimum area of over 100 sq km (10,000 ha). As part of Phase-1, eight urban-industrial nodes in the states have been taken up for implementation work.[7]

Projects under DMIC

The following table gives the details of the investment/ industrial regions that are being developed under Phase-1 in DMIC:[8]

|

Sr. No. |

Name of the Node |

State |

Area (in Sq km) |

|

1. |

Dadri-Noida-Ghaziabad Investment Region |

Uttar Pradesh |

210 |

|

2. |

Manesar-Bawal Investment Region |

Haryana |

402 |

|

3. |

Khushkhera-Bhiwadi-Neemrana Investment Region |

Rajasthan |

160 |

|

4. |

Pithampur-Dhar-Mhow Investment Region |

Madhya Pradesh |

372 |

|

5. |

Ahmedabad-Dholera Investment Region |

Gujarat |

920 |

|

6. |

Shendra Bidkin Investment Region |

Maharashtra |

84 |

|

7. |

Dighi Port Industrial Area |

Maharashtra |

253 |

|

8. |

Jodhpur Pali Marwar Industrial Area |

Rajasthan |

155 |

Among the above, construction related activities have begun at Dholera Special Inverstment Region, Shendra Bidkin Industrial Area, Integrated Industrial Township Project at Greater Noida and Integrated Industrial Township Project at Ujjain.

In each state, a nodal agency has been appointed, which is responsible for coordinating the work on various projects as well as approvals, clearances, monitoring, commissioning and financing arrangements for the projects among others. The state nodal agencies are as follows:

|

Sr. No. |

State |

Nodal Agency |

|

1. |

Haryana |

Haryana State Industrial and Infrastructure Development Corporation |

|

2. |

Uttar Pradesh |

Greater Noida Industrial Development Authority |

|

3. |

Rajasthan |

Bureau of Investment Promotion |

|

4. |

Madhya Pradesh |

Trade and Investment Facilitation Corporation Limited |

|

5. |

Gujarat |

Gujarat Infrastructure Development Board |

|

6. |

Maharashtra |

Maharashtra Industrial Development Corporation |

Project implementation status

The annual report notes that these projects are in various stages of implementation – from the project approval, formation of SPVs and land acquisition to undertaking the construction work. For instance, in Uttar Pradesh the works for Integrated Industrial Township Project at Greater Noida have begun. An SPV named ‘DMIC Integrated Industrial Township Greater Noida Limited’ has been registered and an area of 747.5 acres transferred to it. Shapoorji Pallonji Group has been awarded a contract worth Rs.426 crore for construction works while Siemens has got another contract worth Rs.121 crore for developing internal power infrastructure works. Works related to transmission network has been awarded to Uttar Pradesh Power Transmission Corporation Limited for Rs.156 crore.

For the Global City Project in Haryana, an SPV, ‘DMIC Haryana Global City Project Limited’ was formed. The master plan for the project has been approved and the land is in possession of the state government. However, in April 2019, the state government said that it had terminated the joint venture agreement and the project would be implemented by the Haryana State Industrial and Infrastructure Development Corporation (HSIIDC) on its own.

In Rajasthan, the Ministry of Civil Aviation has granted site clearance for a greenfield international airport. The Airports Authority of India (AAI) is finalising the detailed project report and environmental clearance from the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MOEF&CC) is under process.

In Madhya Pradesh, to implement Integrated Industrial Township Vikram Udyogpuri Project in Ujjain, an SPV named ‘DMIC Integrated Industrial Township Vikram Udyogpuri Limited’ has been formed. The state government has transferred 1,100 acres to the SPV for the project and Subhash Projects and Marketing Limited (SPML) has been awarded contract for various infrastructure works.

In Maharashtra, for Shendra Bidkin Industrial Area, an SPV, ‘Aurangabad Industrial Township Limited’, has been formed. The Maharashtra government has transferred to the SPV 8.39 sq km for Shendra Industrial Area and 13.76 sq km for Bidkin Industrial Area. For Shendra Industrial Area, the Cabinet Committee on Economic Affairs (CCEA) has approved tender packages amounting to Rs.1,533 crore for various contracts that have been awarded to private companies such as Shapoorji Pallonji, Patil Construction and Infrastructure Limited, Honeywell and Passavant Energy. For Bidkin Industrial Area, the CCEA has approved tender packages worth Rs.6,414 crore. Under the approved tender packages, L&T has been awarded the contract for constructing roads and underground utilities and KEC appointed for ICT Master System Integrator (MSI) works. Hyosung Group of Korea has been allotted an industrial plot measuring 100 acres for setting up a ‘Spandex’ manufacturing unit.

In Gujarat, for Dholera Special Investment Region (DSIR), an SPV, ‘Dholera Industrial City Development Limited’, has been formed. The Gujarat government has transferred 30.27 sq km of land to the SPV and matching equity amounting to Rs.1,745.54 crore has been released by National Industrial Corridor Development and Implementation Trust (NICDIT). The CCEA has approved tender packages worth Rs.2,784.82 crore for various infrastructure works. L&T has been selected to implement roads and services contract, sewage treatment plant (STP) and central effluent treatment plant (CETP). Cube Construction Engineering Limited has been awarded building contract and SPML the water treatment plant (WTP) contract.

The India International Convention and Expo Centre Project has been approved by the central government at a cost of Rs.25,703 crore. A fully government owned company, India International Convention and Exhibition Centre Limited, has been registered to implement the project. Land measuring around 89 ha has been transferred on lease to the company for the project. L&T has been appointed as engineering, procurement, construction (EPC) contractor for constructing the trunk infrastructure. Korea International Exhibition Centre and eSang Networks Company Limited (KINEXIN) has been appointed as the operator for the convention and exhibition centre. IDBI Capital Markets and Securities Limited has been appointed as the financial advisor for raising loans for IICC. BSES Rajdhani Power Limited will supply bulk power to IICC. A term loan of Rs.2,150 crore is being finalised by the State Bank of India to IICC. DMRC has been appointed EPC contractor for metro link to IICC via Airport Line Express.

The other investors in DMIC projects include Tata Chemicals, Haier Appliances and AMUL.

DMICDC has also extended the services of its Logistics Data Bank to southern and eastern regions that includes container freight stations, port terminal operators and inland container depots.

DMICDC as Knowledge Partner

DMICDC acts as a knowledge partner to National Industrial Corridor Development and Implementation Trust (NICDIT) in respect of all the industrial corridor projects for undertaking various project development activities.

Financing Projects under DMIC

In 2011, the Government of India approved the institutional and financial structure of DMIC along with a budgetary support of Rs.17,500 crore, at an average of Rs.2,500 crore for each of the seven nodes, over a period of five years for the work on industrial cities in Phase-1. The support goes to DMIC-Project Implementation Trust Fund (PITF) and it provides equity or debt or both to SPVs, joint ventures between the Government of India and the respective state governments for DMIC projects. A revolving Project Development Fund (PDF) has also been created to meet the expenditure of various project related activities and Rs.1,000 crore would be given as grant-in-aid to DMICDC Limited. The allocation of funds against PDF is made in the form of annual grant from the Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion (DIPP). A city level SPV would be responsible for implementing specific projects.[9]

It has been estimated that projects under DMIC require investment of USD 90 billion through PPP mode and for those developed through budgetary allocation. It is assessed broadly that projects of around 75 per cent of the estimated overall investment can be implemented through PPP.[10]

It appears that the funds for PDF would come from various financial institutions including multi-lateral banks, commercial banks, foreign institutional investors, state governments, apart from the Government of India and Government of Japan. A loan agreement between India Infrastructure Finance Company Limited (IIFCL) and Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC) will be signed for DMIC PDF. Government of India will be providing sovereign guarantee to this loan. Preparation of development plans, master plans, and feasibility studies would be financed by PDF. It can also be used for creating SPV companies for projects approved by DMICDC board in the form of providing share capital, unsecured loans, convertible debt or other equity arrangements. Japan External Trade Organisation (JETRO) can also recommend to the investment committee for using funds from the Government of Japan.[11]

The Government of India has also approved setting up a Project Implementation Fund (PIF) for various activities for DMIC. The grant received from the Government of India is used as capital reserves and the interest, dividend or any other income that will be earned on PIF is added to it. If any part of the fund becomes refundable, it will be reduced from capital reserves.[12]

International institutions financing DMIC projects

In addition to those from Japanese bilateral agencies, financial institutions like ADB, International Finance Corporation (IFC) and others have been financing projects that are part of the overall DMIC plan. These specific projects are in states like Rajasthan, Gujarat and Maharashtra. For instance, ADB is financing two technical assistance projects in Rajasthan – Supporting Rajasthan’s Productive Clusters in the Delhi-Mumbai Industrial Corridor and Advanced Project Preparedness for Poverty Reduction - Capacity Development of Institutions in the Urban Sector in Rajasthan.

The former would support industrial cluster development in Rajasthan around Delhi-Mumbai Industrial Corridor. Majority of the area of the state falls within the project influence area and the dedicated freight corridor passes through the state as well. The project looks to improve the state’s competitiveness by creating productive industrial clusters, which is a group of firms closely linked by common product markets, labour pools, similar technologies, supply chains, infrastructure and other economic links[13]. The latter would look to establish corporatised state-level and city level agencies to manage water and wastewater services and promote PPPs, rationalise urban property tax, develop a long-term urban development policy, improve revenue realisation from water and sewerage charges and others[14].

IFC is also investing in creating warehousing facilities for industrial corridors including DMIC through investments in Continental Warehousing Corporation (Nhava Sheva) Limited. The IFC is investing USD 25 million in equity and another USD 35 million as loan for a project costing a total amount of USD 90 million.[15]

AIIB has also proposed financing for integrated multi-modal logistics hub at Nangal Chaudhary in Haryana as part of DMIC.[16]

It has also been reported that DMIC is looking to raise funds from the international equity funds as well as the pension funds in case of shortfall in funding requirements.[17]

Critical issues facing DMIC

Since the inception of DMIC, concerns have been raised by the local communities in different states about the large projects being implemented under it and their serious impacts on the ecology, land acquisition, local economy and livelihoods. DMIC faces scrutiny about the operational mechanisms being used for implementation of projects like creation of multiple SPVs and PPPs. Concerns have also been raised about the role of national and international financial institutions in pushing the projects further, the conditions these institutions impose for driving profits and their impacts on local communities. The issue of wider public consultations and the role of people’s representatives within local governments in decision making processes have been sidelined.

Concerns over environmental degradation, land acquisition, dispossession and loss for agriculture based livelihoods have been voiced by various groups including grassroots organisations, farmers, academics and researchers. Projects implemented under DMIC use land pooling mechanisms for procuring land required for them rather than applying the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act of 2013. It has been argued that land pooling mechanism is ambiguous and misleads land owners to hand over their lands for project implementation.

For instance, in Dholera Special Investment Region land pooling mechanism works by taking 50 per cent of the land of each owner “deducted” at market price, the rest returned to the original owners as “developed” plots in re-designated zones under the new plan criteria. A betterment charge would be levied on the original owners for the provision of new infrastructure facilities, deducted from the compensation award for 50 per cent of the land. In addition, each affected family is promised one job per family in the Dholera SIR. It also includes Dholera Smart City,[18] claimed to be identified as the first smart city in the country twice the size of Delhi and six times of Shanghai. It has already received Rs.3,000 crore funding from the government and looks forward to attract more from private investors.[19]

Land pooling is done under Gujarat Town Planning and Urban Development Act (GTPUDA), 1976 as enabled under the Gujarat Special Investment Region Act, 2009.While the town planning law contains provisions for the participation of local bodies and residents in the determination of compensation and award, it makes no provisions for ascertaining consent to land pooling for the project.

The rezoning under the new plan also sacrifices agricultural land by categorising the land as industrial or urban space. Hence the land owners, who are supposed to benefit from this practice, lose their ability to farm or provide for themselves as they had done before. Another concern with the land pooling scheme is the time frame that the redevelopment requires. The owners will not receive their newly developed land within a year and thus must wait until development is completed.[20]

The Dighi Port and Industrial Area in Maharashtra and Dharuhera Industrial Estate in Haryana have seen protests from local people against land acquisition and setting up industries in the region.[21]

Concerns have also been raised that due to the immense land requirements of the projects under DMIC, these might potentially lead to social issues. DMIC projects have the potential to create land speculation and social conflicts. The potential for social unrest becomes very high when public investment are channelled into real estate and industrial projects without providing basic infrastructure for local industries and population centres. Evidences suggest that large scale infrastructure projects can be associated with increased household and regional inequalities.[22]

Critiques around DMIC also include the environmental impacts that it will have in view of the proposed large scale urbanisation and industrialisation. The land for the greenfield projects will require deforestation in the states that are part of the project. For instance, 70 per cent of mangroves around Mumbai have been lost to land reclamation and other development projects and less than 45 sq km of mangrove forests remain.[23] Land will not only be taken from farmers but also from the natural environments of various types of Indian wildlife. For example, Dholera is planned to be built close to the Velavadar National Park that has a blackbuck sanctuary. Concerns have been raised about how the industrial city will impact the national park that is home to many endangered species. It has also been noted that Dholera will sit within the migratory route of wintering birds to India.[24] The risk associated with the immense deforestation are well known, increased deforestation leads to increased incidences of wildfires, drought like conditions, and depleted groundwater.[25]

The large scale industrialisation that the DMIC envisions will also require immense amounts of water, which will be taken away from farmers and domestic users alike. In areas of Madhya Pradesh and Gujarat already suffering from severe water stress, the implementation of large scale industry will only make conditions worse. It is estimated that DMIC will have to extract two-thirds of the total water need from rivers and the rest from severely stressed groundwater aquifers, which are already polluted and overexploited. It is suggested that the regions where DMIC is planned face groundwater deficit, hence the water would be diverted from the rivers. Though all the utilisable flow in the rivers of the region is already fully utilised by current users, developing DMIC will overdraw the water and impact the health of the rivers as well.[26]

A majority of DMIC projects are being implemented through PPP mode with SPVs being created to execute specific projects. Several instances have shown that the track record of PPPs in India is not encouraging and many of these projects have looked for public support to make them financially viable in terms of grants, loans and concessions.[27] While discussing SPVs, it is important to note that DMIC initially had Infrastructure Leasing and Financial Services (IL&FS) as an equity shareholder in the project, though it appears that equity stake held by it was subsequently replaced by public sector backed entities HUDCO, IIFCL and LIC.

IL&FS has faced legal issues due to its business practices that were revealed in 2010. It was able to use SPVs to skirt checks and balances concerning its business dealings. It managed to allocate project funds to its subsidiaries, which allowed money to be taken from the projects they were intended to fund. SPVs are registered as private entities having near full autonomy. They are tasked with regulating themselves within the scope of what projects they are established for. Using SPVs, IL&FS was able to misallocate huge funds that were supposed to go to projects they were in charge of. It handled many DMIC projects until it was forced to divest from the DMIC in 2013.[28] It is worrisome to consider the potential for mismanagement to happen again bearing in mind that majority of the projects are now implemented through a SPV based model.

Concluding remarks

Over a past couple of decades, India is seeing a surge in push for construction of mega infrastructure projects across the country. These projects have been envisaged to accelerate economic growth and also provide investment opportunities attracting private investors and FDI. Simultaneously, policies and regulations that lead to increased ease of doing business have been brought about with scrapping of several land, labour and environmental regulations in the past few years. PPPs are being promoted in various sectors claiming efficient project implementation and bringing in private investments. However, experiences of PPP projects in different sectors have not been able to match the claimed results. It has been well documented that PPPs raise funds from public sources for their investments as well as other forms of public support for their projects. SPVs and PPPs also lack government oversight and accountability mechanisms and bypass the decision making processes of the local governments and people’s representatives.

All discussions have been about these mega projects and their implementation pushing the economic growth rates to higher levels as well as the huge amounts of investments required. There has, however, been little public debate regarding the implications of these massive projects and investments on the rural and urban communities, agriculture, land and water commons as well as ecological footprints. On the other hand, several financial institutions looking to invest in infrastructure projects lack appropriate environment and social safeguard policies as well as transparency and accountability mechanisms. Such mechanisms are imperative to hold these myriad institutions accountable for the investments they make and the impacts on the local communities in terms of loss of livelihood, displacement, environment damage and claiming appropriate resettlement and rehabilitation. It is all the more important, as increasing number of private investors and market based instruments are used to bring in finance for these projects for creating revenue streams and extracting profits.

Mega infrastructure projects might look good on paper but experiences based on ground realities demonstrate that they have serious implications on the local people, democratic governance processes, natural resources, wildlife habitats and the delicate ecological systems.

Disclaimer: This article was prepared with the support of the Heinrich Böll Stiftung India. The views and analysis contained in the publication are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the Heinrich Böll Stiftung.

Endnotes

[1] IBEF, Infrastructure Sector in India, Source URL - https://www.ibef.org/industry/infrastructure-sector-india.aspx

[3] Annual Report of DMICDC for the financial year 2018-19, Source URL - http://dmicdc.com/Uploads/Files/60df_11thAnnualReport_2018-19.pdf

[4] Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade, Source URL - https://dipp.gov.in/japan-plus/delhi-mumbai-industrial-corridor-dmic

[5] Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade, Source URL - https://dipp.gov.in/programmes-and-schemes/infrastructure/industrial-corridors

[8] Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade, Source URL - https://dipp.gov.in/programmes-and-schemes/infrastructure/industrial-corridors

[9] Annual Report of DMICDC for the financial year 2018-19, Source URL - http://dmicdc.com/Uploads/Files/60df_11thAnnualReport_2018-19.pdf

[10] Centre for Urban Research, DMIC, Source URL - http://delhimumbaiindustrialcorridor.com/financial-analysis-of-dmic-project.html

[11] Ibid

[12] Annual Report of DMICDC for the financial year 2018-19, Source URL - http://dmicdc.com/Uploads/Files/60df_11thAnnualReport_2018-19.pdf

[13] Asian Development Bank, Supporting Rajasthan’s Productive Clusters in the Delhi–Mumbai Industrial Corridor, Source URL - https://www.adb.org/projects/49276-001/main#project-pds

[14] Asian Development Bank, Advanced Project Preparedness for Poverty Reduction - Capacity Development of Institutions in the Urban Sector in Rajasthan, Source URL - https://www.adb.org/projects/43166-216/main#project-pds

[15] International Finance Corporation, Continental Warehousing Corporation (Nhava Seva) Limited, Source URL - https://disclosures.ifc.org/#/projectDetail/SII/36727

[16] AIIB, Source URL - https://www.aiib.org/en/projects/proposed/2019/nangal-chaudhary-integrated.html

[17] DMICDC looks to tap pension, equity funds, The Economic Times, Source URL - https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/infrastructure/dmicdc-looks-to-tap-pension-equity-funds/articleshow/62991939.cms

[18] Dholera Smart City, Source URL - https://www.dholera-smart-city.com/

[19] Smart Cities Mission in India – Footprints of International Financial Institutions by Gaurav Dwivedi, Source URL - https://www.cenfa.org/publications/booklet-smart-cities-mission-in-india-footprints-of-ifis/

[20] The Emperor’s New City by Preeti Sampat, Source URL - https://www.thehinducentre.com/multimedia/archive/02878/Dholera-_The_Emper_2878422a.pdf

[21] Delhi-Mumbai Industrial Corridor: people oppose Manesar-Bawal segment of project at public hearing by Soundaram Ramanathan, Source URL -https://www.downtoearth.org.in/news/delhimumbai-industrial-corridor-people-oppose-manesarbawal-segment-of-project-at-public-hearing-42655

[22] Infrastructure, Institutions and Industrialisation: The Delhi-Mumbai Industrial Corridor and Regional Development in Gujarat and Uttar Pradesh by Shahana Chattarraj, Source URL - https://www.orfonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/ORF_Issue_Brief_272_DMIC.pdf

[23] India lost 40 per cent of its mangroves in the last century. And it’s putting communities at risk by Soumya Sarkar, Source URL - https://www.thehindu.com/sci-tech/energy-and-environment/india-lost-40-of-its-mangroves-in-the-last-century-and-its-putting-communities-at-risk/article22999935.ece

[24] Delhi –Mumbai Industrial Corridor A Hype-Busting analysis, A Study initiated by National Alliance of People’s Movements, Source URL - https://file.ejatlas.org/docs/DMIC_Report_I_Rishit.pdf

[25] 23,716 Industrial Projects Replace Forests Over 30 Years by Himadri Ghosh, Source URL - https://archive.indiaspend.com/cover-story/23716-industrial-projects-replace-forests-over-30-years-82665

[26] Delhi-Mumbai Corridor A Water Disaster in Making? By Romi Khosla, Vikram Soni, Economic & Political Weekly, March 10, 2012, VOL XLVII No 10

[27] IL&FS Scam: Justice DK Jain Approves Transfer of Gurgaon Metro Link to HUDA by Moneylife Digital Team, Source URL - https://www.moneylife.in/article/ilfs-scam-justice-dk-jain-approves-transfer-of-gurgaon-metro-link-to-huda/58124.html

[28] A many layered circus: Riddled with conflict of interest, IL&FS exposes the underbelly of our governance by Gajendra Haldea, Source URL - https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/blogs/toi-edit-page/a-many-layered-circus-riddled-with-conflict-of-interest-ilfs-exposes-the-underbelly-of-our-governance/