How do we read a non-western world in order to address to a global problem?

Western rationalism and scientific reading of the self and the universe is based on a binary between culture and nature, a divide that paves way to heighten human supremacy over the non-human world. This modernist thinking tracing back to Rene Descartes, later taken up by scientific reading of social life, creates a table of hierarchy with man on the top and the rest of the nature as means for human fulfillment. Fiddling with nature heightened by this perceived supremacy has not only led to continuous destruction of nature, but also emergence of several anomalies. The present crisis created by novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is a case in point.

The last few decades have seen emergence of intellectual discourses critiquing scientism and western logic. Philosophical and anthropological studies (including that of Andreas Weber) have been highlighting the significance of indigenous thought and beliefs, showing finer conceptions of humans, persons and the environment, and non-divisibility of culture from nature. There are, however, challenges about use of vocabulary and methods of engaging with the indigenous. Works of these western philosophers and cultural anthropologists still fall within the discourse advanced in/ by the West. So, understanding the indigenous worldviews still remains methodologically incomplete.

Of all the crises that humankind has faced in the last many decades, environmental catastrophe stands out with most alarming tone. Starting from ozone depletion and melting of glaciers, to the filth in rivers and oceans by industrial pollutants, smog in the cities, leakages of oil, poisonous gas and viruses from factories and laboratories − the list is long. And one can keep on adding. Climate change and ecological imbalance are turning out to be most troublesome crises of our time. But the irony is: What the modern man has failed, a virus has checked the ecological imbalance by default! It shows that nothing is indispensable – even the neo-liberal mode of production and growth.

Environmental crises owe their origin to the kind of scientific epistemology and development models originated in the West, shaped by what was earlier called the ‘Enlightenment rationality’. Today what the West does symbolise what is global; it has lured the entire global south to follow one master narrative – the vertical graph of growth, development and wellbeing. So, it is no more a crisis of the developed world alone, but of the developing world too. The development model of the West is informed by a worldview initially peculiar to the West. The absolute distinction between the human and the non-human world, human beings as ‘end/goal’ and the non-human world as the ‘instrument/means’ for the fulfillment of the end, come from a specific kind of epistemology (knowing) and ontology (being). This worldview requires serious scrutiny.

The essay under review entitled, ‘Sharing Life. The Ecopolitics of Reciprocity’ by Andreas Weber engages with western scientific worldview raising serious questions on their validity and legitimacy. Weber gives an alternate reading of ecological issues mentioned above. He raises some fundamental flaws in the theoretical presuppositions of man and the universe. He goes back to the ‘world of animism’, which the colonial discourses despise as tribal and primitive. This bold move is well supported by alternate theoretical perspective showing sign of paradigm shift.

The strength of the essay lies in showing close linkages between what we, as a people, do and think. Weber sees, and quite correctly, that much of the collective human actions, which are environmentally hazardous comes out of our indifference towards the non-human and the inanimate. This is the result of an ontology built by the modernist outlook in the West.

Development discourse and crises of western ontology

For more than a century now, development has remained the key word for human progress and well-being. With development and growth as uncompromisable dicta, the challenge for the western science and law makers has been to address to the world how to sustain this development without completely exhausting the (natural) resources. Enough information has already been shared in the public domain on how fast we are using the non-human means to satisfy human ends. The idea of renewable energy, for instance, is one part of our attempts not to exhaust the resources. But in spite of the political propaganda of sustainable development, climate change and ecological imbalance have not reduced. The renewable energy project is again being implemented only through the ‘lenses of developmental analysis’ often leading to destruction of the very nature it is aiming to protect, e.g. leading to water shortages due to cleaning needs of huge solar parks, de-settlement of indigenous communities or disbursement of nomadic grazing grounds.

Addressing this crisis, according to Andreas Weber, requires a relook at the philosophical ground upon which western science is built. Development perspective makes a clear-cut distinction between ‘that which is to be sustained’ and ‘for whom sustenance is aimed’. Another distinction is between ‘development that is uncompromisable’ and ‘devising methods with least side effect that sustains development’. (The latter can be understood better in the light of what is being presented in the previous paragraph). Both these parameters are shaped by a hierarchical worldview where man is at the top, whose vertical growth and material wellbeing are facilitated by the non-human world. To put it simply, the non-human world is for the consumption of the humans. So, growth and well-being of humankind is to be achieved by acting upon the nature and the non-human, by transforming these for human benefit. So, the nature and other non-humans possess instrumental value, whereas humans are intrinsically valuable. This is an unfortunate theoretical premise. It is upon this binary that emergence and development of western science and technology are shaped. Weber sees that western science and epistemology is programmed on the basis of the above-mentioned binary, articulated further through the distinction between culture and nature. The theoretical position is that humans are value seeking beings; their life is marked by culture. On the other hand, nature is seen as brute and naked. It has no value or meaning.

Since this science has gained tremendous success in terms of description and measurement of the bodily existence of the universe (including the human), the West continues to remain at the centre of all the major popular discourses. And with it goes the philosophical worldviews that not only support, but also trigger the methods and practices of the western science. The Cartesian mind, on which the dictum ‘I think, therefore, I am’[i] is set, becomes the ontological foundation. Man, as a thinking being, and the rest of the beings as incapable of thinking, is the point from where human arrogance starts. Man is seen as the epicentre of scientific revolution that is capable of not only mapping the universe, but also transforming the same. Western science lures the humans to think that they can become God!

In spite of man being shown his place time and again, the arrogance hardly dies. Since it is the scientific mind that ‘maps’ and ‘transforms’ the universe the arrogance is not going to go away. This struggle to rule the universe is still visible in the face of the COVID-19 crisis. While COVID-19 has contributed in balancing the ecology by default, human endeavor to produce vaccine is yet again an attempt to reverse the new trend and create a human norm. On a lighter note, perhaps human arrogance emerged from the day Adam and Eve ate the forbidden fruit!

Need for an alternative

Andreas Weber takes a drastic approach as an alternative to the ‘global’ trend. Here is an approach that signifies the importance of indigenous values and ways of life as means for sustaining the value of nature and the Anthropocene. Weber takes up the indigenous philosophical thoughts from several continents of America, Africa and Australia though he also acknowledges that lived life of an indigenous community cannot be generalised. However, his dealing of the indigenous concepts is generic and carries universalising tendency, as are the works he refers to, whether it is Bruno Latour[ii], Nurit Bird-Davis[iii] or others. This, of course, cannot be an issue of criticism as concepts when handled have to be dealt in abstraction and cannot be locked down by the particularity of practices. Thoughts always carry the tendency to generalise, and that is how humanity connects.

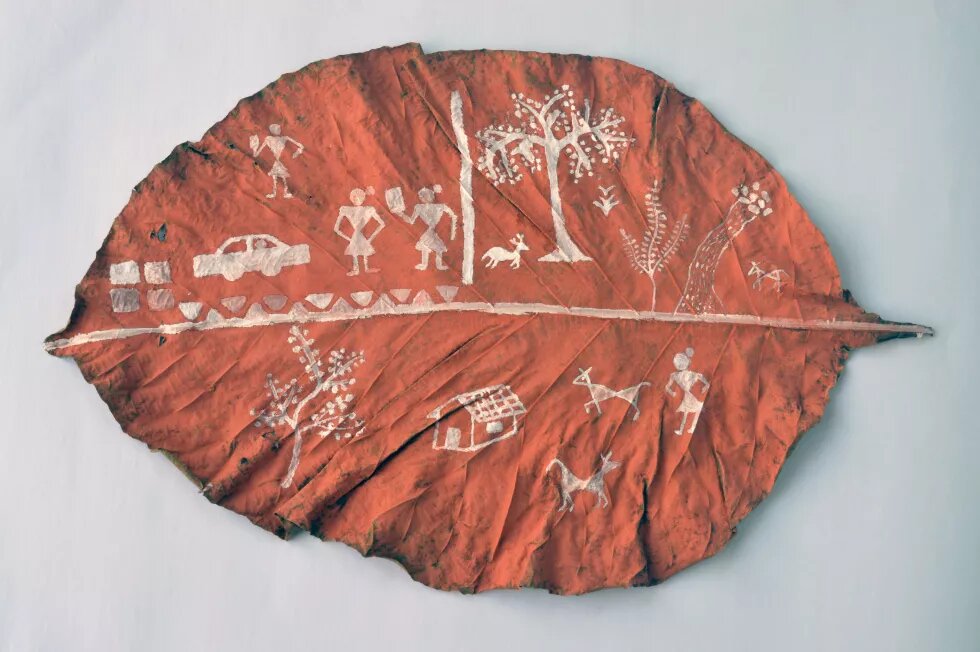

The highlight of the alternative is brought out through the concept of ‘reciprocity’. Though reciprocity is also a popular idea in the West, particularly in the Continental philosophy (and also in Judaism), the author uses it as a unique way of life of the indigenous peoples. Unlike the western ontology where the issue of being is centred around human existence, for the indigenous it is continuous interaction among different constituents of nature (humans included). Humans do not have a privileged or superior position over the non-humans. For the indigenous segregation does not work upon the animate and the inanimate, human and the non-human. Rather there are spirits present in all things in nature – whether it is stone, tree, birds, animals, humans, and the moon. One interacts with the other marked by reciprocity. Bird-Davis’ comparison of modernist epistemology with animist epistemology in that former is ‘cutting trees into parts’ and latter is ‘talking to trees’ is a fascinating description rich in philosophical content[iv]. Equilibrium defines the life of the indigenous.

These traditional beliefs of reciprocity and equilibrium are prevalent among the non-modern and non-western world. Let me add here one fascinating creation myth from Ao Naga community of Northeast India. The Ao community believes that they emerged out of ‘lung terok’ (six stones). The interesting part of the myth is the multiple readings of the same myth. A closer look will reveal where these readings are coming from in terms of methodological ground. The first narrative goes with an explanation informed by political and anthropological studies of space, origin, memory and identity. This narrative highlights a place called Chungliyimti in the present Tuensang district of Nagaland as the place of their origin. Beyond this place Aos do not carry any folk memory. These six stones are supposed to represent six clans of the Aos. It explains the community’s effort to mark the symbols of origin, unity and identity[v]. On the other hand, there are literary and cultural readings of worldviews emerging out of the traditional meanings and values. In this narrative these stones comprise three males and three females[vi]. The second narrative is fascinating in the sense that this subject matter is not to be seen from the prism of truth and falsity. It is independent of scientific yardsticks unlike the first narrative. This narrative further breaks the realist reading of the inanimate. Gendering the stones should be seen as traditional way of reciprocity between the animate and the inanimate, and thus imagining and anticipating equilibrium in the universe. This narrative can be connected with Graham Harvey’s[vii] articulation that in animism the world is full of persons – stone person, human person, bird person, etc.

Animism and the problem of discourse

Andreas Weber uses the term ‘animism’ to explain the philosophical (or cosmological) worldviews of the indigenous. While he has categorically explained that indigenous communities do not use the term ‘animism’ to represent their worldview, he uses it in continuation to what the colonial scholars have used. Perhaps he does it with a purpose. As far as I can see, Weber uses the term ‘animism’ to take it out of the valuational frame of colonial discourse where animism is seen derogatorily as primitive thought and practices of the ‘tribes’.

Referring to Harvey that animism is a belief that world is full of persons (as mentioned in the previous section) and life is lived in interaction among persons, Weber further highlights the belief that there is spirit (as sign of life) in everything in the world. This thought breaks the realist bifurcation of the animate from the inanimate, and human from the non-human. Similar thought is being expressed by Sri Aurobindo[viii] (the 20th century Indian saint and philosopher) that there is spirit/energy in every being including that we call ‘inanimate’. Sri Aurobindo’s philosophy is deeply spiritual and built on the classical Indian philosophy, particularly Advaita Vedanta, where oneness of the spirit is conceived out of the multiplicity of spirits. Such a philosophical thought is not considered animist, but spiritual and metaphysical – a narrative of unqualified monism[ix]. One can see parallel thought in Plato’s ‘world of forms’ in classical Greek philosophy.

Weber’s recourse to animism as a solution to better understanding and living is well taken. The idea of inner experience and further sharing of this experience are novel ideas. It is through reciprocity that persons share and benefit from one another. These traits of animism, as Weber sees, provoke one to compare and contrast between the indigenous and western scientific worldviews. This exercise has been attempted by Weber, but looks less convincing.

Let me put two points for quick reflection. Firstly, western philosophy is not one but many. There have been debates and contestations among different schools. One such example is between analytic-continental divide until the emergence of philosophers like Dan Zahavi and several others. Similarly, indigenous communities engage different ways of articulating their philosophies. There could also be meeting points between indigenous philosophy and continental philosophy. For instance, Heidegger’s critique of technology[x] and reference to ‘enowning’[xi] may find similar resonances in the indigenous philosophy. So, the tables of differentiation provided by Weber foreclose the possibility of exploring the grey areas.

Secondly, animism as an alternate philosophy to western epistemology is not a complete bifurcation. Animism is a western concept addressed to the non-western world by the western scholars. So, this debate is a family debate within the western philosophical discourse. It is not meeting of two distinct traditions. At least the writings of Andreas Weber seem to give this impression.

Is there an alternative to the ‘alternative’?

I think this is an important question. How do we read a non-western world in order to address to a global problem? I have stated in the introduction that problems of the global south are largely backwater problems of what the global north has been facing. As much as technological, economic and political practices have been appropriated by the non-western world, the remedy even in the form of indigenous comes through western lenses. This looks quite obvious. I am not suggesting that non-western world give up the western paradigm. Ideas have no boundary, and we are moving towards a free world. Yet, there could be a way out!

When Heidegger coined the term ‘Dasein’[xii] (‘there-being’ or ‘being-there’), he could have simply stated ‘authentic human’. Language is not merely a symbol of communication; it is much more than that. It is a world in itself. The terms like ‘self’, ‘man’, ‘being’, etc. have a long history of journey carrying the baggage of meaning and values. Dasein got rid of all the baggage – foremost, it got rid of traditional western discourse of explaining human existence through rationality, mind and consciousness. Dasein highlights human existence (ontology) with embodiment, yet inseparably linked with doing/acting/engaging in one’s mundane mode of living. I think Heidegger was undoubtedly smart.

Is not ‘animism’ too heavy a word? Philosophy of animism will fail to bring out the rich and diverse senses derived out of deeper experiences of collective lives, and the rich metaphysical articulation of the oneness of the spirit. Animism, as already defined through certain perspective, cannot come out of its original habitation. And this habitation lies in the colonial ‘life-world’. I do not know how Weber and others can refine and bring out the ‘pristine nature’ of animism. My fear is simply that. Rest, the intention and commitment, and boldness with which the author ventures out for an alternative worldview to western ontology, is commendable. I believe a dialogue has started!

Endnotes

[i] I am referring to Descartes’ famous dictum ‘Cogito ergo sum’ (I think therefore I am) whereby one’s existence is defined by the capacity to think or reason. See Rene Descartes, Discourse on Method and Meditation on First Philosophy, trans. Donald A. Cress, Heckett, 1998.

[ii] Down to Earth: Politics in the New Climatic Regime (Polity Press, 2018), and We Have Never Been Modern (Harvard University Press, 1993).

[iii]“ ‘Animism’ Revisited: Personhood, Environment, and Relational Epistemology,” Current Anthropology. 40 (S1), pp. S67−S91.

[iv] This is being described by Weber in the present paper.

[v] This narrative is gathered through the interviews conducted on several Ao respondents (as many as six) from various parts of Mokokchung district and Dimapur in Nagaland as part of an IGNCA sponsored field research during 2013. (Interview was conducted by Asangba Tzudir, and the author was the principal investigator).

[vi] See the work of Temsula Ao, The Ao - Naga Oral Tradition. Heritage Books, Dimapur, 2012.

[vii] See, Graham Harvey, Animism: Respecting the Living World, Columbia University Press, 2005.

[viii] See, Sri Aurobindo, The Life Divine. Lotus Press, Pondicherry, 2005.

[ix] The idea of ‘unqualified monism’ expresses that reality is inalienable one (singular) in spite of being perceived sensorially as multiple. This idea initially found in the Upanishads and Brahma Sutra is being popularised through his commentary by Adi Sankaracharya in the philosophical thought known as Advaita Vedanta. For details, see S. Radhakrishnan, Indian Philosophy, Vols. 1 &2, Oxford India Paperbacks, 2008.

[x] Martin Heidegger, ‘The Question Concerning Technology’, trans. W. Lovitt, in D.F. Krell (ed.), Martin Heidegger: Basic Writings, Routledge, 1993.

[xi] See, Martin Heidegger, Contributions to Philosophy (From Enowning), trans. P. Emad and K. Maly, Indiana University Press, 1999.

[xii] See, Martin Heidegger, Being and Time, trans. J. Stambaugh, State University of New York Press, 2010.

This contribution is part of Alternative Worldviews.