Rejuvenating agriculture infrastructure is the key to sustainable growth

Distress migration of youth from rural India to cities due to lack of livelihood opportunities and rising climate impacts is deeply worrying for Indian economy. Although the present government announced several measures such as rural housing, toilets and better road network for rural development, they have failed to yield overall progress in rural sector. Besides, impetus to budget allocations for rural livelihood mission and employment guarantee schemes has not shown promising results.

Constant downslide in the rate of economic growth, business investments and employment indicate an inherent flaw in the country’s development framework. The rural infrastructure calls for a redesign so that it boosts rural economy through integrated planning of fostering small businesses, job creation, expanding irrigation network, agriculture and allied sectors. The novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic further exposes the dangers of lopsided development where a major part of the country lives under the shadow of shining urban India that has taken an unsustainable path to prosper. India needs a deeper analysis of what is going wrong and where.

This external content requires your consent. Please note our privacy policy.

Open external content on original siteI sit in a remote village in one of the routinely flooded panchayats on the banks of Kosi river in Saharsa district of Bihar and wonder what type of magic mantra would really transform this sleepy hamlet into a self-sustained economy where people are not forced to migrate to far off lands to earn and support their families back in this village. Is it just the roads that are missing? Or education? Maybe skill or could be jobs? What is that one missing link between our villages and their development, or are there plenty of them?

India in the year 2020 is still struggling to find answer to the same old question that arose way back in 1947 when the country attained Independence – “What development model should we choose to put India on the rails of economic growth?” While Gandhi insisted that Gram Swaraj (or village self-rule) was the only way we could strengthen our nation and its economy from within, Nehru saw modern science and technology as the panacea for uplifting Indians from abject poverty that was staring at our face at that point in time. Seven decades later, when the country is grappling with an unprecedented blow of novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic, the confusion between choosing self-reliant rural India or growth propelling urban India surfaces more clearly. Images of millions of migrants walking back to their villages at the time of crisis puts a big question mark on the development trajectory that India has taken. Big cities could not promise them protection from this crisis of survival and these migrants looked towards their own homeland for seeking refuge.

India’s development pathway – a retrospective view

Looking back at the unfolding of consecutive Five-Year Plans ever since the commissioning of a planning institution by India’s first prime minister Pandit Jawahar Lal Nehru in 1950-51, one can see how the lawmakers designed the trajectory of development of an India that was struggling to feed its people, explore and exploit its natural resources like land, water, minerals and energy, and make the country self-reliant. Infrastructure development was always at the centre of our growth story, be it irrigation, transportation, communication and industry. Agriculture was ‘modernised’ with heavy inputs of research, developing new high yielding varieties, thrust on growing wheat, paddy and oilseeds, use of technology for agriculture and food processing for making India self-reliant in food. Similarly, large dams were built, irrigation channels were laid to provide water to dry lands too. While all this was happening in the rural hinterland, a new industrial India was also taking shape with cities and townships being developed around industry and mining centres. Import duties were raised on capital goods and more emphasis was laid on manufacturing our own goods in order to create a circular economy that stays within the country. The defence sector was getting strengthened, especially when the country faced wars on its north frontiers. ‘Jai Jawan, Jai Kisan’ (hail the soldier, hail the farmer) was the slogan central to development and self-reliance until Rajiv Gandhi, the sixth prime minister of India from 1984 to 1989, led the Sixth Plan and brought industrialisation, information technology and rapid transportation to the core of development.

With the policy thrust more on seeing cities as propellers of growth, infrastructure development became more urban and gradually rural India turned into a source from where cities could attract human resource. Thus, a country that was largely agrarian with approximately 85 per cent people engaged in agriculture at the time of Independence, India started transforming itself into an industrial economy where rural youth became job seekers in labour market.

Open market, structural reforms and urban infrastructure becomes the key to attain high GDP leaving rural India to fend for itself

Post Gulf War, India faced a major financial crisis that occurred in the late 1980s so much so that the country was in deep debt and was forced to pledge its gold reserve to International Monetary Fund (IMF). As a result, in 1991, IMF and the World Bank compelled India to adopt the Structural Adjustment Programme (SAP) that had begun in the mid-1980s and unfolded itself later in its myriad forms. India became a member of WTO and entered the global market seeking investments to ‘uplift’ its sinking economy. The famous liberalisation-privatisation-globalisation (LPG), phenomenon was set in under the iconic leadership of the then prime minister P.V. Narasimha Rao and his finance minister Manmohan Singh, and the country started readying itself for receiving foreign direct investments (FDIs).

In 1993, 74th Constitutional Amendment[i] Act was brought in the Nagarpalika Act 1993, which mandated major urban reforms, giving power to municipal bodies for local self-governance, handing over the responsibility of local area development to the local governments and also pushing municipalities to raise their own funds and perform in the best interests of people.

The greatest vehicle to bring this urban overhaul was the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM). Launched in the year 2005 in select 65 cities, JNNURM had two submissions – Urban Infrastructure and Governance (UIG) and Basic Services for Urban Poor (BSUP). The motive was very clear: Cities must improve their infrastructure and living conditions of poor in cities should be improved by providing them basic services. Therefore, the major reforms brought in to expedite the processes under JNNURM were – Financial Management Reforms, E-Governance Reforms and Pro-Poor Reforms.

The landscape of India’s urban centres was thrown open to 100 per cent FDI in infrastructure development. The Urban Land Ceiling Act was repealed, public private partnership (PPP) mode of working was initiated and urban India was declared as ‘engine of growth’ for the country. Amidst this hullabaloo, rural India was left to fend for itself.

Interestingly, in the same year, in fact much before 74th Constitutional Amendment Act, another amendment – 73rd Amendment of the Constitution – was brought in by the government to push the famous big reform for devolution of power for rural governance by bringing in the role of panchayati raj institutions (PRIs). With this, the then ruling party, Congress, could realise the dream of Gandhiji’s Gram Swaraj. Gandhi always advocated for seeing villages as mini republics where people were the decision makers and implementers of holistic development. Could the villages really become so is a debatable question, though. What is clearly visible is that rural India became a land bank for an ever-expanding urban India. All the roads to development towards villages were only to bring migrants as cheap labourers and infrastructure merely serving for industrial and information technology (IT) development.

In the absence of any real financial powers or specific budgets, PRIs became mere vehicles of implementing projects decided at the top, rather than planning for their specific village development in a bottom up approach that could touch lives of rural community, build assets and infrastructure relevant to village centric development. Moreover, caste equations and cultural hegemonies have also played a huge role in disallowing Gram Sabhas to perform their mandated functions. Over a period, these last tiers of local governance have become a sheer formality losing their significance in the integrated development of rural India.

Could a ‘Structurally Reformed Smart India’ become the solution for development?

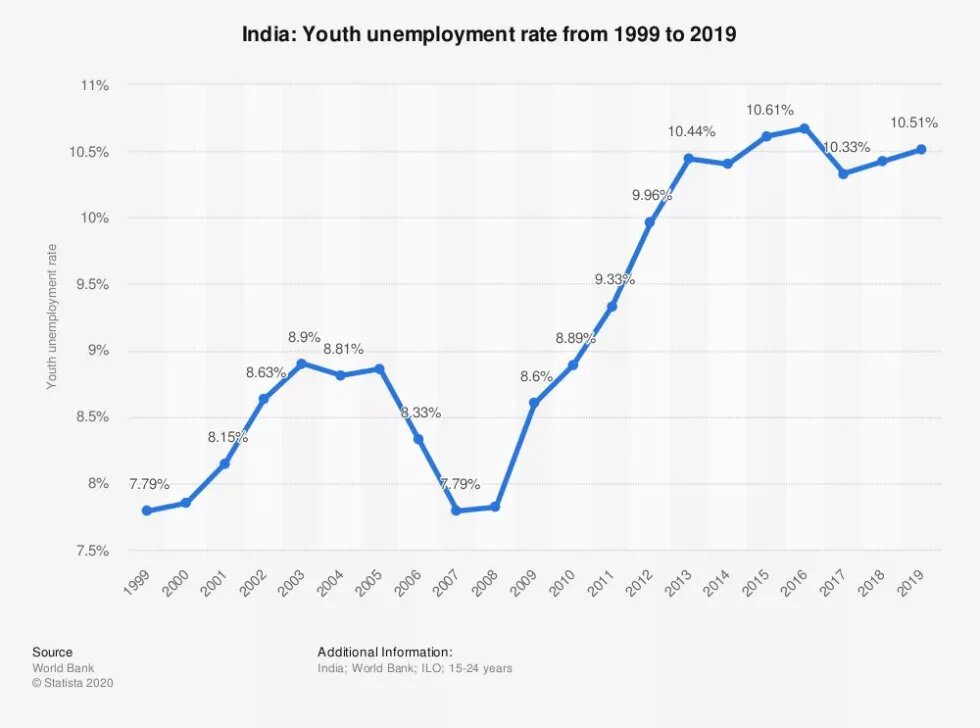

When India opened its markets for foreign direct investments, the hopes were sky high. Metro and other capital cities were being modernised with better transport network, industrial corridors were getting built, special economic zones (SEZs) were being created to welcome multinational companies set up their manufacturing units, and IT parks were introduced. To feed these high speed vehicles to development, the education sector also started opening up to privatisation of professional education with more and more colleges coming up to create a pool of human resource for the new found management and service sector. Employment rate zoomed up and surpassed its targets. GDP was skyrocketing and urban infrastructure, especially construction industry, was reaching new heights. However, beyond a point, this growth could not take the country anywhere. A look at the graph showing youth employment rate[ii] narrates the story well.

Youth unemployment rate in India 1999-2019

This graph released by the World Bank and UN’s International Labour Organisation (ILO) sums up where we are after four decades of having opened up our economy to the western model of private markets, industries and fast speed development.

After a landslide victory in the general elections in 2014, the newly elected Modi government tried to repackage urban renewal mission into a new avatar – Smart City Mission[iii]. It was supposed to be their attempt at modernising urban India that aimed at building urban infrastructure with modern technology providing smart solutions to urban population. The focus however remained technology, mechanisation and corporatising solutions. Integrating urban poor community’s basic needs of social security, employment, education and health in this development model is still a missing link.

Today, India appears to be at a standstill. From P.V. Narasimha Rao-Manmohan Singh era to Modi-Shah regime, the economy has stagnated and is at the risk of going further down with barely touching GDP at 5.5 per cent in 2019-20. Youth lack modern employability and whole country is seriously looking for solutions. This is a classic case of getting stuck in a quagmire. Fast economy requires huge investments, world class infrastructure, automation, modern technologies, skilled professionals and committed buyers. Unfortunately, this modernisation could not provide employment to our youth who were in millions but without matching skills and potentials. Not surprising, large and erstwhile large-scale employers like mining industry, construction work and manufacturing were now being run on sophisticated machines that gradually removed manual labour and the jobs went from workers to trained professionals.

Agriculture and allied sectors that were the large source of employment bore the brunt of this race to achieve modernisation. Agricultural lands, especially adjoining major cities, were acquired by the governments in the name of national interest and huge land banks were created so that new era industries could be set up. Farm owners turned landless, rendering farm labourers jobless. While the former still had some cash to invest in the world that they were not aware of, the latter had nothing in their hands. As the country was moving on a fast track, large part of farming community was paying the price of this speed.

Since then, several analyses have time and again concluded that the agriculture sector that was the largest employer completely crashed and therefore India finds itself stagnant and now sinking in terms of economic growth, overall development indicators and employment.

The Modi government has been working on multiple strategies for “Doubling farmers’ income by 2022” and one of the big ticket reforms claimed by the government is the Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services Bill, 2020. However, instead of becoming a matter to celebrate, this bill is facing severe opposition from farmers and policy lobbies across the nation. The biggest critique of the new Act is that while it brings down the marketing committees set up in the previous Act, APMC Act, 2003[iv], and gives farmers the freedom to sell their produce across the nation, the new Act does not provide any regulation over minimum support price (MSP). Hindustan Times, a national newspaper has quoted[v] Kavitha Kuruganti, an activist representing Alliance for Sustainable and Holistic Agriculture (ASHA), highlighting the most contentious issue in the new Act: “The government is abdicating all oversight responsibility since it is not prescribing a system of registration of all traders of farmers’ produce, nor does it want to build a price intelligence system even as it weakens the mandi (market) system. How and when will it intervene then?”

With corporates coming in as big players in food sector, the risk of farmers getting unfair share due to power imbalance is quite evident and government opting out of the system puts farmers further at the mercy of private companies.

The stir is going on, farmers are not letting this go and the nation waits to see how this stalemate gets over and in whose favour.

Responsible and responsive alternate pathway to revive rural economy

Niti Aayog in its Discussion Paper[vi] in 2017, “Changing Structure of Rural Economy of India – Implications for Employment and Growth”, authored by Ramesh Chand, S.K. Srivastava and Jaspal Singh mulls over the plight of agriculture as a sector in India and how the loss of jobs in this sector is a big factor in the stagnant economic situation of India. The paper highlights that contribution of the rural areas in the economy of India for the period 1970-71 to 2011-12 is seen from its share in national output and employment (Table 2.1). The rural areas engaged 84.1 per cent of the total workforce and produced 62.4 per cent of the total net domestic product (NDP) in 1970-71. Subsequently, rural share in the national income declined sharply till 1999-2000. Rural share in total employment also witnessed a decline but its pace did not match with the changes in its share in national output or income. The declining contribution of rural areas in national output without a commensurate reduction in its share in employment implies that a major portion of the overall economic growth in the country came from the capital-intensive sectors in urban areas without generating significant employment during the period under consideration.

Rural India and MGNREGAhttps://nrega.nic.in/netnrega/home.aspx[vii] In 2005, the Manmohan Singh government passed a landmark Act, National Rural Employment Guarantee Act 2005 (NREGA), which later became Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA). The sole purpose of the this Act and then the programme was to generate employment in rural India for both men and women so that poor in rural India could get employment in their native place, lead a better life and were not forced to migrate in search of work, simultaneously building infrastructural and productive assets in villages that could respond to people’s needs. This was indeed a path breaking programme that was aimed at transforming rural India if it were to be implemented in letter and spirit. Assets built through MGNREGA funds range from soil and water conservation related work, farm ponds, reviving old water bodies to building new ones for ground water recharge, irrigation, drainage, plantation, land development, rural housing and related work, livestock related infrastructure development. However, time and again, review reports on implementation of MGNREGA have highlighted the fact that the programme is facing a variety of obstacles ranging from political whims and fancies, and bureaucratic bottlenecks causing restricted fund flow, social and caste hegemony in villages and corruption at various levels of fund transfer. The successive governments have always tried to plug the holes but the challenges have been unlimited. With the advent of direct bank transfer (DBT) and geotagging, the implementation seems to be improving but the real question is whether the ambit of MGNREGA is enough to cater to the real infrastructure needs of the villages. The Modi government used MGNREGA to mitigate work and wage crisis in rural India during lockdown period in COVID-19. Quoting government data on the utilisation of funds[viii] for 2020-21 in MGNREGA, an article in Business Standard reports that almost 63 per cent of the increased allocation of around Rs.1.01 trillion was already spent in the first five months of the financial year. |

Rural India needs infrastructure that rejuvenates local livelihood and promotes circular economy

Structural reforms, urban makeover, SEZs, FDI in retail, infrastructure put together have failed to give livelihood to rural India. In fact, the whole dream of “ripple effect” and “trickle down” approach of modern economy could not reach far and wide villages of India and do any good to the backbone of India – its agriculture.

This laid-back village, I am sitting in, is water rich and therefore best for production of paddy, wheat, makhana (fox nut) and freshwater fish, besides a range of vegetables and lentils. However, there are two major problems. First, the landholdings have become very small over a period and in most of the Kosi river affected belt, it is inundated for large part of the year, making it difficult to produce enough grains. Second, in the absence of any wholesale mandi facilitated by the government, traders buy the produce at much bargained price not reaching anywhere near the MSP declared by the government. In the absence of any exposure to value addition to their raw produce they end up selling it to the regular traders.

What villagers share is echoed well in an analysis[ix] presented by the Centre for Budget and Governance Analysis (CBGA): “We can’t expect demand to increase as 70 per cent of our population lives in rural areas and has stagnant incomes and wages. There is a need for revival of the rural economy with infrastructure investment and structural reforms. Agricultural marketing reforms should be a priority. For better price discovery, agriculture has to go beyond farming and develop value chains comprising farming, wholesaling, warehousing, logistics, processing and retailing. Agricultural exports should be promoted with various policies. Similarly, rural infrastructure and water management are other priorities. Stimulus and structural reforms can raise farmers’ prices and wages and rise in demand for manufacturing and services.”

Microenterprises established by and for rural youth is the need of the hour. Farmers of this village in Bihar can set up microenterprises that add value to the farm produce, pushing the product into supply chain. But how is this possible? Is the private sector interested in investing in rural India? Prima facie it seems difficult. First and foremost, the government must invest in rural infrastructure to develop roads, electricity, bridges, education and health.

Rajju Shroff, president of Crop Care Federation of India (CCFI) and MD of United Phosphorus Limited, has urged[x] the government to treble India’s share in agri exports. He says: “India ranks second in global agriculture production at $367 billion and we have potential to double farmer’s income and increase agri export to $100 billion by 2020.”

The Rural Infrastructure Development Fund managed by the Reserve Bank of India's subsidiary National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD) is mandated to bring infrastructure development to rural India. However, due to several bottlenecks in implementation, it is not getting fully utilised by the states. This is putting a negative impact[xi] on the utilisation of priority sector lending (PSL) quota available with the banks. PSL includes lending for agriculture, micro and small enterprises, education, and housing sector. One leading to the other is what is creating a slowdown in the rural areas.

Pumping money into investments in rural infrastructure not only creates durable assets in the long run to make the economy efficient, it also creates consumption demand in the short run, by putting money in the hands of construction workers, painters, electricians, masons and so on. As the private sector is reluctant to invest in rural areas due to low profitability, it should come directly from government investments in construction of rural roads and housing in terms of the viability gap in funding and housing subsidies. Public investment in rural infrastructure will in turn attract private investment with the expected increased profitability being a major incentive.

Skilled rural youth meeting global standards is the next infrastructure input

Infrastructure does not limit to only roads, toilet, water and electricity. Professional skill and sustainable livelihood are the next milestones to be achieved by the country. We must make our youth skilled to match the expectation of global quality standards.

A very interesting study published in EPRA International Journal on Economic and Business Review, Impact of Globalisation on Economic Growth in India[xii], by PC Jose Paul, analyses the economic growth journey of India right from 1990-91 till 2014-15 and why we are still struggling in the economic sector despite completely changing gears from a socialist model of growth to corporate model borrowed from the west. While India started producing for foreign markets, our products could not meet the quality standards set by those markets. There were serious issues of lack of qualified labour, machinery, technology. Besides, social issues like child labour and caste discrimination also played a crucial role in our products not winning the markets. Quite interestingly, the sectors – agriculture, textiles and leather – that could have been ace contributors to our GDP performed the lowest.

The Ministry of Rural Development is undertaking two initiatives in skill development[xiii] under the National Rural Livelihood Mission (NRLM). The Deen Dayal Upadhyaya Grameen Kaushalya Yojana (DDU-GKY) is a placement linked skill development programme, which allows skilling in a PPP mode and assured placements in regular jobs in an organisation not owned by the skilled person.

The Rural Self Employment Training Institutes (RSETIs), thereby, enable the trainee to take bank credit and start his/ her own micro-enterprise. Some of such trainees may also seek regular salaried jobs.

As per the government data released for 2018-19, both the schemes surpassed their targets of skilling rural youth, but surprisingly it has not shown any impact in the employment/ livelihood status of India’s youth. The reasons for this failure are many. Our education system fails to connect youth with employment, where the whole focus is on scoring marks and getting ranks. Skill development programmes too fall short of achieving their promised outcomes, where, again, the number of students undertaking courses matters more than number of youth getting employed. Having realised the shortcomings in both education and skilling programmes, the current government has embarked upon a new education policy and newer approach to Skill India Mission. Debates and analyses on both of these are yet to happen.

Challenges and impediments in skilling India

A very thought provoking article[xiv] in The Pioneer by agricultural economist S Amarendar Reddy clearly emphasises that the buck now stops at strengthening rural infrastructure to produce export class products. He writes, “The goal of crafting a $5 trillion economy by 2025 is only achievable if rural India grows by 12 per cent per annum. In spite of increasing urbanisation in the last decade, the rural economy still contributes about 46 per cent to the national income. Once a predominantly agrarian economy, now rural India is more diversified, with the non-agricultural sector contributing to about two-thirds of household incomes.

“Most of the SMEs (small and medium enterprises), livestock and horticulture sectors have a huge export growth potential, which also provides high productive employment for the rural youth and generates more profits for the private sector. These sectors also provide quality employment and absorb educated youth with higher labour productivity in the post-harvest units, food processing industry and export sectors.”

To infuse a new life and spirit in the times when the whole country is grappling with the economic breakdown post COVID-19 infused lockdown, Prime Minister Narendra Modi has launched a Rs.20 lakh crore worth of campaign titled Atmanirbhar Bharat (self-reliant India). This is a nationwide campaign to motivate youth to become entrepreneurs, work on their dreams and explore new avenues of enterprises. The new pitch of development is now ‘Vocal for Local’, which also influences consumers to buy local and strengthen local enterprises.

One of the fundamental challenges is of poor educational background with even basic literacy levels being a tough ask in the present generation of youth. Any livelihood model requires some amount of computer literacy, technology handling, book-keeping and a clear understanding about quality standards for selling. Reaching global standards comes at a much later stage. Hopefully all this is taken care of in the new National Education Policy 2020[xv] that has been approved by the central government.

In states like Gujarat, Rajasthan, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh, rural livelihood has seen a direct connect with global market and the youth can see the way towards setting up their own micro enterprises. However, when I look at the rural youth in several other states like Uttar Pradesh, Bihar or Madhya Pradesh, I fail to find any such orientation whatsoever. Finding a sundry job in Punjab, Delhi, Noida or Mumbai is the aim and beyond this, youth largely have no vision in the absence of any guidance and efficient government infrastructure.

Instead of luring multinational corporations for investments, rural micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) must be promoted at a large scale by the government. Availability of microcredit, livelihood counselling centres and Jan Suvidha Kendras (public facility centres) style assistance to youth for setting up their own work, linkage with market, either direct or through mid-sized traders, exhibitions, buyer-seller meets even in remote areas, should be organised by the government.

If all the recommendations put forth by a number of intellectuals and economists are implemented with passion and commitment, one day this village on the banks of river Kosi in Bihar will have its own ‘Makhana Snacks’ making unit, fish drying and canning system, wheat and lentil based healthy products, which will employ rural population, put money in the hands of the people and propel a circular economy.

Small is beautiful, they say. Let us think small, think diverse and see how more and more people can be employed in micro industries based out of Indian villages, in their natural resource, promoting local skill and work towards Gandhi’s India that was self-sustained, ecologically responsible and left no one behind. I am curious to see how the design and spirit of an Atmanirbhar Bharat enthuses the dampened spirits of villagers, especially youth in Saharsa in Bihar, the first Indian state that went to polls post COVID-19 pandemic.

Disclaimer: This article was prepared with the support of the Heinrich Böll Stiftung India. The views and analysis contained in the publication are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the Heinrich Böll Stiftung.

Endnotes

[ii] https://www.statista.com/statistics/812106/youth-unemployment-rate-in-india/ (Accessed on 10 February 2020)

[iii] http://smartcities.gov.in/upload/uploadfiles/files/What%20is%20Smart%20City.pdf (Accessed on 7 December 2020)

[iv] http://agricoop.nic.in/sites/default/files/apmc.pdf (Accessed on 7 December 2020)

[vi] https://niti.gov.in/writereaddata/files/document_publication/Rural_Economy_DP_final.pdf (Accessed on 7 December 2020)

[vii] https://nrega.nic.in/netnrega/home.aspx (Accessed on 7 December 2020)

[xii] https://eprawisdom.com/jpanel/upload/articles/1131pm19.Dr.%20P.C.%20Jose%20Paul.pdf (Accessed on 7 December 2020)

[xiii] https://rural.nic.in/press-release/training-and-employment-rural-youth (Accessed on 7 December 2020)

[xiv] https://www.dailypioneer.com/2019/columnists/thrust-on-rural-india-must.html (Accessed on 7 December 2020)

[xv] https://www.education.gov.in/sites/upload_files/mhrd/files/NEP_Final_English_0.pdf (Accessed on 7 December 2020