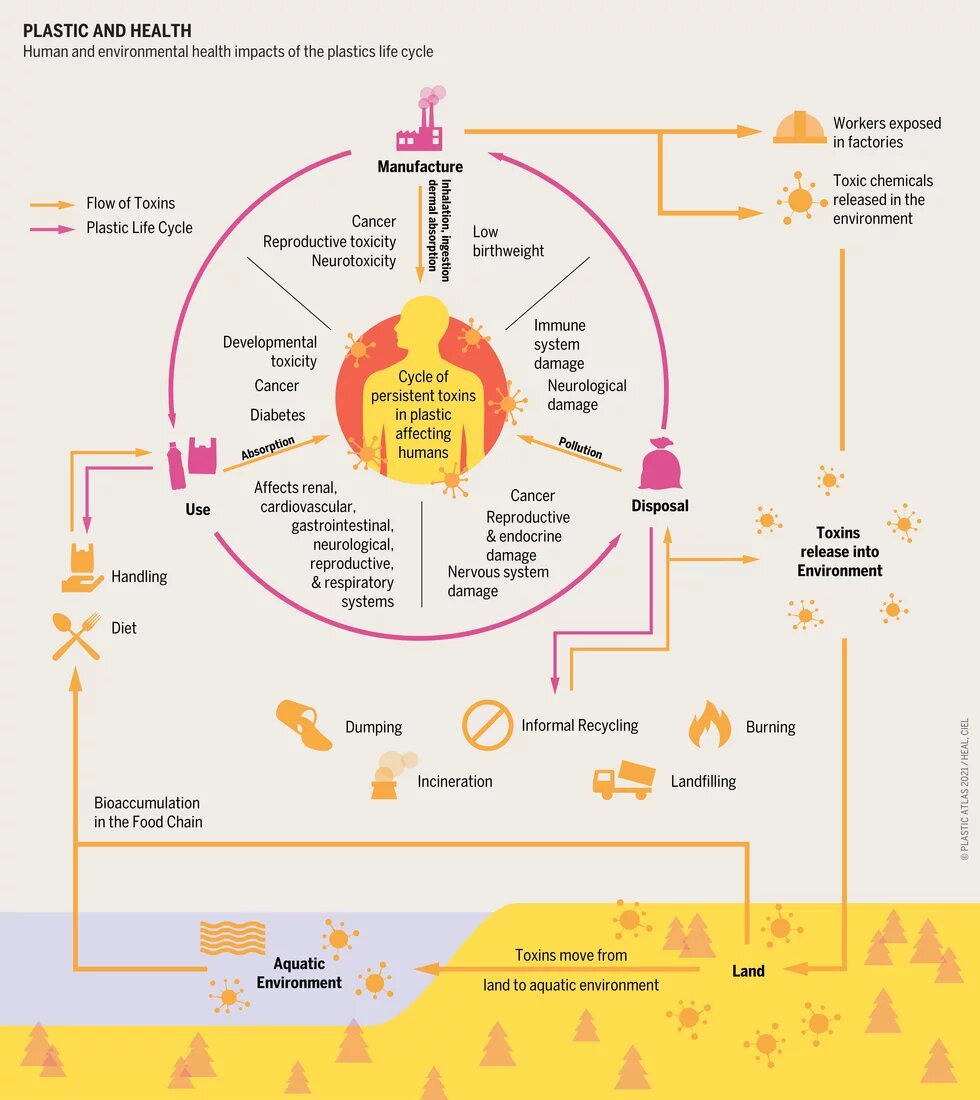

Plastics have critical and irreversible effects on human health, from the extraction of the raw materials needed to create them to the disposal of end products. The ubiquity of plastics in modern life is compounding this.

From production to use, and finally to disposal, plastics interact with the environment and human health in multiple intersecting and overlapping ways.

Plastics are derived from fossil fuels, namely oil and natural gas. During extraction of these fuels, especially through the controversial fracking technique, toxic substances are released into the air, water, and soil.

Over 170 substances used in fracking are known to cause cancer, reproductive and developmental disorders, and damage to the immune system. People living near fracking wells are especially affected by these substances, as well as by pollution from the many diesel trucks used for transportation in such areas.

Plastics produced as a result of fracking in the United States are destined mostly for export markets, including Asia. While Asia has vast reserves of shale gas of its own, the region’s fracking boom has yet to match that of the USA and Europe.

What is already prevalent in Asia is the petrochemical industry, which brings its own health hazards. Scientists from Mahidol University in Thailand have studied people living near petrochemical facilities, and found significant associations between exposure to industrial air pollutants and adverse effects on residents’ health, including shortness of breath, eye irritation, dizziness, coughs, nose congestion, sore throats, phlegm, and general weakness.

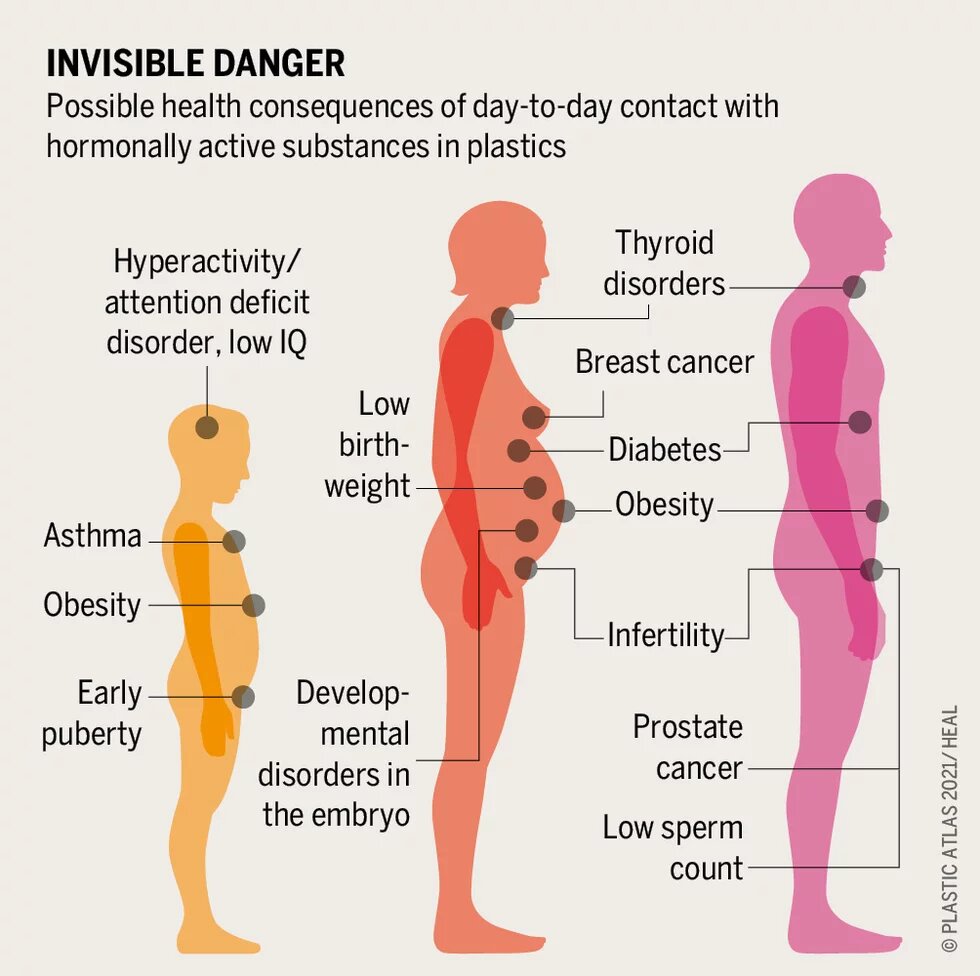

Most humans today ingest, breathe, and come into skin contact with harmful chemicals from plastics. Absorption of plastics and their additives has been linked to cancer and hormone disorders. Plants such as lettuce and wheat absorb plastic nanoparticles from contaminated soil and water, incorporating them into the food chain. Microplastics have been found in honey and beer. On land and in the sea, wildlife often mistake plastics for food and ingest them.

Fish and crustaceans that are eaten whole (without removing the gut) – for example, sardines, anchovies, shrimp, urchins, and mussels – are of particular concern. Microbeads and microfibres accumulate in these animals, exposing humans to the toxins when the creatures are consumed. Microplastics have even been detected in human placenta, carrying substances that could cause long-term effects on foetuses.

A report in 2017 by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations said that salts used in products from Asia have been found to contain more microplastics than those from Europe, North and South America, and Africa, with Indonesian sea salt having the highest amount of microplastics.

Separately, tests in Hong Kong SAR found that 20 percent of commercially available sea salt samples contained microplastics, with many attributable to disposable polypropylene packaging. Meanwhile, studies conducted on soil around a large open dump in Cambodia’s capital Phnom Penh revealed high levels of dioxins, ascribed to the burning of plastics that comprise 15 percent of total municipal waste.

Plastics continue to affect human health even after being thrown away. As plastics degrade in dumpsites and landfills, the additives they contain leach and eventually percolate into the environment, leading to contamination of soil and water.

Even in open dumping conditions where they are exposed to the sun, plastics release methane and ethylene, two deadly greenhouse gases. Polyethylene is not only the most commonly produced and discarded type of plastic, it is also the most prolific emitter of these gases.

When burned in the open, plastic products release pollutants which cause respiratory disorders if they are inhaled. Some of the chemicals released in the fumes easily convert to vapour and disperse over areas beyond the immediate vicinity of incineration or burning sites.

Soot and ash settle on plants and the soil surface, while rainfall washes down these toxic chemical compounds into the soil and water. Some of the chemicals then react when in soil or water, altering chemical properties and affecting the functioning of ecosystems.

Open burning is often used by low-income neighbourhoods in Asian countries to deal with poor waste collection services. In addition, in many Asian cities, municipal staff burn waste in open dumpsites to reduce the quantity.

In Sri Lanka, many households do not have waste collection services and have resorted to burning their plastic waste. Informal waste pickers burn plastic layers of e-waste to retrieve the metal components within.

In Kolkata, India, where municipal waste is regularly burned, high levels of dioxins were found in the breast milk of mothers in the area due to the consumption of fish from a local pond.

In the Philippines, open burning was practised until it was banned under two landmark national laws: the Republic Act (RA) 8749 or Clean Air Act; and the Republic Act (RA) 9003, otherwise known as the Ecological Solid Waste Management Act of 2000.

Despite the growing amount of information on the adverse effects of plastics on human health, the full extent of the impact remains unknown. Meanwhile, businesses are not mandated to fully disclose the chemicals in their plastic products and packaging, limiting consumers’ ability to make informed choices.