The first plastics produced by scientists and industry in the west imitated ivory and silk, and attracted a limited market. Cheaper production led to the rise of mass popularity globally. Today, Asia has become the largest plastic producer and consumer in the world.

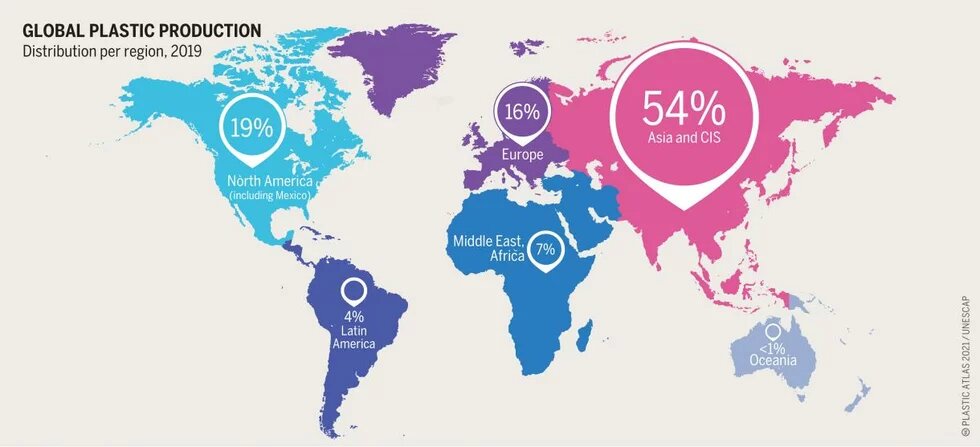

Plastics are now a part of everyday life for billions of people. They are also extensively used in industry. Some 368 million tonnes are produced annually, with Asia accounting for more than half of global plastics production.

But what exactly are plastics? The word refers to a group of synthetic materials made from hydrocarbons. They are formed by polymerisation, a series of chemical reactions on organic (carbon-containing) raw materials, mainly natural gas and crude oil.

Various types of polymerisation make it possible to produce plastics that are hard or soft, opaque or transparent, flexible or stiff. In addition, plastics can be manufactured to be lightweight while retaining many of their other useful properties. This makes them highly popular for packaging.

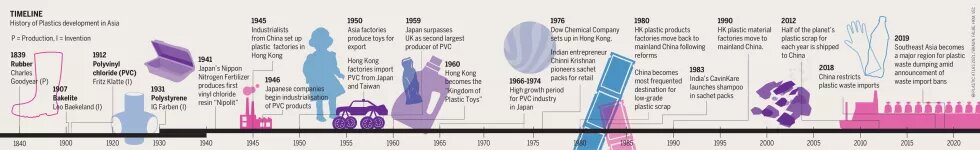

The first plastic was presented at the Great London Exposition in 1862. Called Parkesine after its UK inventor, Alexander Parkes, the organic material was derived from cellulose, and could be shaped when heated and retained its shape on cooling.

Since then, plastics have undergone numerous stages of development. At the outset, the materials began by replacing ivory and tortoiseshell in billiard balls and combs. This then led on to the creation of synthetic plastics that were cheaper than silk and other natural fibres.

Next came the popularisation of polyvinyl chloride, better known as PVC, or vinyl, which did not contain any naturally occurring molecules but proved a good insulator and a durable, heat-resistant material.

Wide adoption did not occur immediately, with plastics occupying a relatively small market niche until the mid-20th century. The trigger for the mass spread of PVC was the discovery that it could be made from a petrochemical industry waste product. World War II also created significant demand as PVC was used to insulate cables on navy ships.

These key events marked the start of the rapid and uninterrupted rise of PVC for a huge range of industrial and household products. Alongside, two other plastics gained broad acceptance: polyethylene for making bottles for drinks, shopping bags, and food containers; and polypropylene, which became popular in the 1950s and is used today for packaging, child seats, pipes, and other everyday products. PVC, polyethylene, and polypropylene are now the most widely used plastics in the world.

In Asia, plastic factories were already present during World War II. After the global conflict ended, the civil war in China forced the country’s plastic manufacturers to flee to Hong Kong, where they started the first plastic factories in the mid-1940s. Meanwhile, Japanese companies began to scale up PVC product production.

In the 1950s, Hong Kong began producing plastic toys and flowers, mostly for export to Southeast Asian countries, and Japan became the world’s second-largest producer of PVC.

By the end of the 1960s, Hong Kong's factories were making toys for US giants Hasbro and Mattel, and by 1972, the city had become the largest exporter of plastic toys in the world. Following economic reforms in China in the late 1970s and early 1980s, Hong Kong-based manufacturers started moving production back to the mainland but still maintained offices in Hong Kong.

While China and Japan lead the way in plastic production in Asia, Vietnam, Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia, and the Philippines have all seen rapid growth in the past decade, exporting plastic products to Europe, China, Singapore, Japan, and other countries and regions.

Efficient business processes combined with lower labour and production costs have made these factories highly competitive, enabling Asia to garner 51 percent of global plastics production capacity by 2018, and plastic products to become one of the region’s top export industries.

Down the decades, a positive image of plastics contributed to the boom in use worldwide. Plastics were seen as trendy, clean, and modern. They squeezed out existing products and muscled their way into almost all areas of life.

In the 1970s, an enterprising businessman from India pioneered the use of plastic sachets for selling fast-moving consumer goods in micro-retail quantities. Products sold in plastic sachets are now widely used in the region, marketed by both multinationals and Asian companies.

However, the same properties that make plastic appealing to producers have also created problems. To make a single plastic bag takes 13.8 millilitres of crude oil. With eight billion plastic shopping bags being disposed of in landfills each year, that amounts to US$28 million of crude oil literally going to waste every year.

By 2016, plastics also made up 12 percent of global solid waste by mass, with plastic waste rising to 15 per cent in Asia. About half of all plastic waste that ends up in the oceans comes from just five countries: China, Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam.

This mountain of plastic waste is bringing disastrous consequences to Asia and needs to be tackled. A further problem is that Southeast Asian countries continue to be inundated with plastic waste imports from within and outside the region.

Along with reducing and reusing plastic products, the three current approaches for managing municipal solid waste in Asian countries are recycling, waste-to-energy conversion, and disposal at landfills. All have their limitations.

More optimistically, a new generation of bioplastics – made from materials such as sugarcane and cassava – may contribute to solving the plastic crisis. In addition, a novel production process that creates a polymer known as chitosan from crustacean shells is being used to make a biodegradable plastic. However, with little track record as yet, whether such materials can make a substantial difference remains to be seen.