Localisation of infrastructure and adaptation actions for a green and resilient recovery for India in pandemic times.

Hosting G20 Presidency in 2023 is a fitting aspiration and a welcome challenge for India. A major economy and a developing country with a mature democracy, heading into its 76th year of its independence, India has the unique opportunity to set ‘Agenda 2023’ with a focus on equitable green and resilient recovery. The groundwork must begin now, to embrace the troika, and soon after the presidency. India can showcase the standards, practices and policies being developed to align with 1.5-degree target, adaptation readiness for building resilience of its most vulnerable while strongly highlighting the need for industrialised countries of the bloc to do much more. The government will have to begin working together with civil society organisations, think tanks, businesses, youth and women to deliver on Agenda 2023 and the agenda of G20 that responds to the COVID-19 pandemic, climate and inclusive sustainable development.

G20 in a COVID-19 era is poised to be remarkably challenging. Faced with a global pandemic that has undone years of gains in reducing poverty, adding[i] more than 100 million new extreme poor, the sharpest global economic contraction since World War 2, while battling multitude of climate extremes, poses formidable challenge for a sustainable future for all. However, the recovery action being taken by G20 countries, a group that has repeatedly affirmed the mutually reinforcing links between a strong economy and healthy planet for sustainability, is a matter of serious concern. These leading economies are directing trillions of dollars towards COVID-19 recovery packages[ii], but a significant proportion of it towards fossil fuel industries without climate-related conditions, risking clean energy transition. Such recovery pathways by the most powerful economic bloc, whose carbon reductions are way off of what is required to reach goals of Paris and net zero by 2050, indicate a lack of courage and conviction to stand by its own commitments of inclusive sustainable growth. In this context, the upcoming presidencies of the next decade beginning with Italy in 2021 and India in 2023 assume greater significance.

Looking at India specifically, high development deficits together with high vulnerabilities to climate change[iii] with grim future projections, where extreme events are only going to increase in scale and intensity largely affecting the most vulnerable people and locations, put it in a rather tough spot. The course that India has taken for economic development so far has not benefitted the most vulnerable, whose numbers have increased during COVID. The ongoing COVID recovery process gives little hope of sustainably addressing the socio-economic or climate crisis. The auction of 41 coal blocks in forested areas of the Eastern Ghats[iv], a response for job creation and revenue generation, is a case in point. This thinking is reflective of many such linear short term responses taken during the pandemic, which has conveniently skirted equity, environmental concerns and long term sustainability questions.

This paradigm can change and transformation could be round the corner if India acts with courage and vision. The year when India hosts the G20 Presidency is a year after it celebrates its landmark 75th anniversary. As the country prepares to embrace its role as G20 host, which is still two years away, it provides a unique opportunity for it to build and showcase an alternate economic model – one that is built on localisation and decentralisation. The localisation narrative sits cosily well in the larger call for Atmanirbhar Bharat (a self-reliant India) by the Indian Prime Minister and the catchphrase “be vocal for local”. There could be no better time and opportunity to get the jargon out and translate it into meaningful actions at multiple levels. It has a one-time opportunity to be an unparalleled leader to posit an economic model built on social progress Index with a focus on its people, environment and wellbeing.

So, what models of decentralisation and localisation should India present to G20 and to the world? And how should India go about it?

The concepts of localisation and decentralisation are not new. What is new is the context, which is constantly evolving with multiplicity of challenges with ever increasing complexities. Two actions that India should immediately focus considering its unique context towards setting Agenda 2023:

a) Build ‘socially relevant’ and climate resilient infrastructure through an ecosystem based[v] partnership model

b) Build adaptation readiness through a decentralised “people’s centre of excellence (PCoE) on adaptation”

Both these issues are at the core of G20 action agenda of the Climate Sustainability Working Group[vi]. Let’s take them one by one.

Building socially relevant and resilient infrastructure that works for the people and the planet

The current spate of infrastructure development in India has largely skirted aspects of climate resilience, human rights, disaster risk and pro-poor perspectives. The COVID-19 experience brings this to the forefront. Infrastructure development has so far been dominated by large scale energy, water, urbanisation and transport projects, now more than ever even as new age green banks like the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank ( AIIB) struggle to make the committed shift from brown to green. While energy projects are witnessing a promising shift to renewable energy (RE), which is decarbonising the grid, the approach of RE projects – predominantly taking place through megawatt and gigawatt solar and wind projects, having high land, livelihood and water footprints – is worrisome. Decentralised models of energy are yet to receive required attention. Scaling up of proven decentralised energy models related to micro-grids, improved biomass cooking stoves for both rural and urban area, waste to energy models needs to be aggressively promoted by policy measures for a low carbon infrastructure and positive health. The service micro-grids, which have taken off successfully in some parts of our country, need to be upscaled in a big way to boost access to affordable and reliable electricity for rural homes and enterprises. Synchronised to grid through a net metering system can further enhance rural livelihoods by generating additional revenues. This approach will promote green entrepreneurship, job creation, while also contributing to lesser pollution and overall wellbeing, which matters much more than India’s GDP figures. Further, infrastructure for ensuring last-mile delivery of healthcare services through RE based systems to rural primary health centres (PHCs) needs special focus. Solar rooftop systems can meet the needs of lighting, refrigeration, water pumping, and, in many cases, permit the use of advanced medical equipment in health facilities. Solar-powered refrigerators should be popularised for storing vaccines required for pandemics like COVID-19. Anganwadi centres (day care centres) and government hospitals in urban areas should be retrofitted with pavilions for shade, plants on facades and roof, install water dispensers to counter increasing heat stress.

Further, investing in the right type of infrastructure with community participation can be a game changer for India. Beginning with designing low carbon, climate proof, affordable and resilient housing for the poor, critical infrastructure for irrigation, storage, transport systems needs to be planned in synergy with the participation instead of a top-down mechanism. Well meaning efforts to create community centric water infrastructures through farm ponds and tanks have been promoted through the government flagship programme like the Mahatma Gandhi Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MNREGS). However, the productive use of these infrastructures remains questionable. Further most of these infrastructures are not built on low carbon principles and are not climate and disaster aligned. India has had a long tradition of community determined, local level water systems for drinking as well as irrigation[vii], However, these systems in many places are in a state of neglect or replaced by modern water systems. Investments in water infrastructure are crucial for India to achieve its economic, social development and environmental goals. Resurrection of community level water infrastructure becomes a compelling policy measure in a water stressed landscape. A radical policy reform to invigorate these traditional systems cannot wait. Universalisation of such socially relevant infrastructure together with better management measures can respond to the ongoing water crisis and a turbulent water future. This will perhaps also serve as the least cost approach. It is important for a country like India to remain relevant to its unique country context and to send the message that the story of infrastructure creation must not begin with the asset but instead with its people – specifically, the needs of some of the poorest and the most vulnerable in rural and tribal India. This is the outlook that India should forge ahead with as it looks at an estimated infrastructure investment of over $1,000 billion by 2022.

Having said that, let us also recognise that the development of infrastructure is not going to be straightforward anymore. India has learnt some key lessons from past disaster experiences where risk reduction and preparedness are slowly seeping in. The growing focus on early warning systems and making infrastructure financing risk-informed should guide us in responding to the ongoing pandemic. However, to ‘build back better’ is to ‘build back green’ and ‘build back resilience’ that can absorb shocks from emergent and multiple disruptions. To build infrastructure that responds to flooding events together with a virus outbreak as was experienced in West Bengal, Odisha and Maharashtra during the super cyclonic storm Amphan and Cyclone Nisarga. Traditional disasters risk assessments will quickly have to manoeuvre to integrate emergent hazards like pandemics with the traditional ones. The 2019 Global Adaptation Report notes that making new infrastructures resilient – especially critical infrastructures like hospitals, schools, community centres, and evacuation shelters – provides a benefit-cost ratio of 5 to 1. The benefits of resilient infrastructure, if done properly, can support the resilience of the most vulnerable populations who are socio-economically affected by the converging risks.

One approach to do it properly could be through an ecosystem based partnership model.

India would stand to benefit from setting up ecosystem based infrastructure commission, which could define long term infrastructure needs, prioritising and planning for the next 30 years. The commission could bring in participation from the local community, women, youth, local government representative, research institutions and entrepreneurs/private sector. Participation in co-creating their own low carbon and resilient infrastructure through the process of planning, development, operation, maintenance and use could also lead to creation of green jobs for young people in towns and villages who otherwise migrate to live like aliens in inhospitable cities. The role of private sector here should be that of a ‘socially responsible’ partner by:

a) bringing in innovative financing mechanism

b) innovation in ecosystem-based resilience design

c) development of ecosystem specific standards and codes

d) support updated climate information and data to prioritise decision-making for resilient infrastructure, including nature-based infrastructure.

This could serve as a potential ecosystem-based partnership model for resilient infrastructure with the people at the core who will put it to use. The government in turn could come up with ecosystem-based reports that show efforts towards integration for resilience in infrastructure development manifesting a decentralised approach to developing people centric infrastructure. Such reports in various languages should contribute to wider public understanding of the level of preparedness to climate and other hazards from a local level to the national level. This model should be up and running to be presented by India as a G20 host.

A community driven micro ecosystem strategy for ecosystem restoration – demonstrating adaptation readiness

Understanding the importance of efforts on adaptation and resilient infrastructure and recognising the potential for synergies of such efforts, the G20 members have been discussing adaptation and resilient infrastructure since the G20 Hamburg Summit in 2017 under the German Presidency. The socially relevant infrastructure pathway could extensively improve India’s adaptation readiness score[viii], which scores well below the G20 average in the recent Climate Transparency Report. On similar lines, transformation of ‘farming’[ix] through adaptation actions for small and marginal farmers will serve to improve adaptation readiness and more importantly serve as a paradigm shift for a green recovery. Eighty five per cent of farmers are small and marginal cultivating on two hectares of land often in fragmented fashion with large credits and negligible surplus. The increased area under cultivation during COVID-19 pandemic points to a potential equitable green recovery pathway for India. These actions during the pandemic have shown early signs in countering contraction in other sectors. India should build on this momentum by fixing its systemic ills, listening to the protesting farmers and taking on the opportunity to demonstrate the transformational power of people centric adaptive practices as it embraces the G20 Presidency. Traversing on this trajectory will present an opportunity for India to be seen as an adaptation leader by contributing to the G20 Adaptation Work Programme where India’s contribution has so far been insignificant. Among the heaps of multilateral adaptation actions, India finds a mention only once, specifically the one in relation to a GCA[x] effort, “Bridging the gap: Financing Sustainable Infrastructure”. The G20 list of adaptation actions offers lessons to be learnt from countries like Japan, Germany, Canada and France. Most of these adaptation actions by these countries are largely technology centric following the larger western adaptation paradigm. Alternatively, India should bring in adaptation actions, which are not only technology fixes but those that reduce vulnerability and build adaptive capacity of the most climate vulnerable. Ongoing initiatives on climate friendly sustainable farming approaches that ensure food and nutritional security, which includes Low Carbon Farming (LCF), zero budget natural farming (ZBNF), organic farming and regenerative agriculture models, are being practised and promoted by government programmes and also by NGOs. These, however, are very patchy and isolated examples with less than 2 per cent of land in lndia under organic cultivation. Mainstreaming organic and natural farming will address the ecological, economic and existential crisis in Indian farming landscape. This demonstrates the immediate need to identify best practices across ecosystems and develop documents with definitions and methods on low carbon climate resilient sustainable farming. India should demonstrate leadership by assuring commitment to at least 50 per cent of agricultural land under organic farming across each state in the next one year and strengthen linkages with non-farm rural economy to foster goals of food and nutritional self-sufficiency, climate resilient and economically secure (Atmanirbhar) farmers and villages. This coverage should reach 100 per cent by 2025. This could serve to build local inclusive economies that contribute to ecosystem resilience, ensure food security, improve health outcomes, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and contribute to sustainable development goals related to 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 12, 13 and 15. These adaptation actions align with the G20 commitment to promote “responsible agricultural investments”. India should explore investments and demonstrate with explanation of what responsible agriculture investment means or how such investments will contribute to mitigating emissions, building resilience and addressing entrenching inequality. To begin with, this will require bold policy decisions to set the stage for reforms, starting with the existing chemical fertiliser subsidy regime. The commissioning of new public sector urea plants should be immediately revisited in the light of unsustainability of the subsidy regime and more importantly for concerns around ecosystem resilience and sustainability. During COVID-19, India earmarked Rs.650 billion ($8.71 billion) as extra subsidy to ensure adequate availability of fertiliser to farmers. Policy decisions should instead be directed towards:

a) incentivising organic fertiliser

b) capacity building on local adaptative mechanism with men and women farmer groups, self-help groups (SHGs), farmer producer organisations (FPOs)

c) upskilling young farmers with renewable based technology for value addition of agriculture produce

d) research and development to develop ecosystem-based farming systems based on scientific climate projections and indigenous knowledge

e) gender responsive, low carbon and energy efficient, time saving farming technologies, especially for women who are increasingly working as agricultural labourers

f) upscaling climate resilient sustainable farming practices such as revival of millet cultivation together with millet processing RE technologies, especially to ensure nutrition adequacy among vulnerable groups such as women and children who are lowest in the health index and highest on climate impacts.

These policy directions should be part of ecosystem based strategies for safeguarding livelihoods, biodiversity and reviving ecosystem restoration. India is already committed to restoring 26 million hectares of land by 2030 as part of the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration. However, an ecosystem-based restoration plan is still missing. This has to begin now. Any revival plan for the acute problem of ecosystem degradation with significantly increasing GHG emissions[xi] from land use and land use change sector should centre on building resilience of the poor. One such ongoing effort on afforestation has been towards promoting ‘community determined’ species[xii] in a forest ecosystem. A fully capacitated and functional decentralised “people’s centre of excellence on adaptation” across all ecosystems is needed where such a centre could support participatory adaptation planning and actions by local stakeholders, including the governments and scientists, to achieve goals of increasing adaptive capacity and climate resilience by combining traditional and scientific knowledge through an integrated approach.

India should ensure corporate commitments to eliminate deforestation, and ecosystem conversion, for example, from forestry supply chains that produce, process, use and sell forest-based products and have a huge responsibility towards safeguarding ecosystem. Initiatives like Accountability Framework, which is a civil society initiative, should be strongly adhered to and strengthened. Sustainably managed ecosystems can lay foundation for resilient economies and societies capable of withstanding future pandemics, climate change and other global challenges. The upcoming Convention on Biological Diversity (CBDCoP 15) is a unique opportunity to strengthen commitment through a robust post 2020 global biodiversity framework. India can show the way to the world.

Going forward: Integrate local practices to deliver policy targets

As we embark on the Decade on Ecosystem Restoration, with huge goals of restoration and conservation, with additional goals of poverty alleviation augmented by COVID-19, sustainable livelihoods, nationally determined contributions[xiii] and SDGs, India’s G20 agenda must recognise that people centric partnership models need to be facilitated and strengthened, and integrated meaningfully into policy directions for meeting local, national and global targets.

Endnotes

[i]This is the first time in 20 years that global poverty rates will go up, according to the biennial Poverty and Shared Prosperity Report. Most of the ‘new extreme poor’ will be in middle income countries that already have high poverty rates.

[ii]19 of the G20 countries have chosen to provide financial support to their domestic oil, coal and/or gas sectors and 14 countries bailed out their national airline companies without climate conditions attached.

[iii]With an average, 2,925 fatalities and almost USD 14 billion yearly losses due to extreme weather, India is ranked as susceptible to “very high” impact in a 1.5°C scenario. A Germanwatch study of 2019 placed India second among G20 countries in annual economic losses.

[iv]The blocks are located across Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Odisha and Maharashtra.

[v]The Ecosystem Approach is a strategy for the integrated management of land, water and living resources that promotes conservation and sustainable use in an equitable way.

[vi] In the G20 framework, the Energy Sustainability Working Group (ESWG) was established in 2013 to cover the all energy-related issues. In 2017, considering that energy policy and climate change issues are closely linked to each other, the Climate Sustainability Working Group (CSWG) was newly established under the Sustainability Working Group (SWG).

[vii]Taankas in Rajasthan, pokhri in Uttar Pradesh including jharalas and bawaris, dobahs in Jharkhand, dongs in Assam and many such systems in other states.

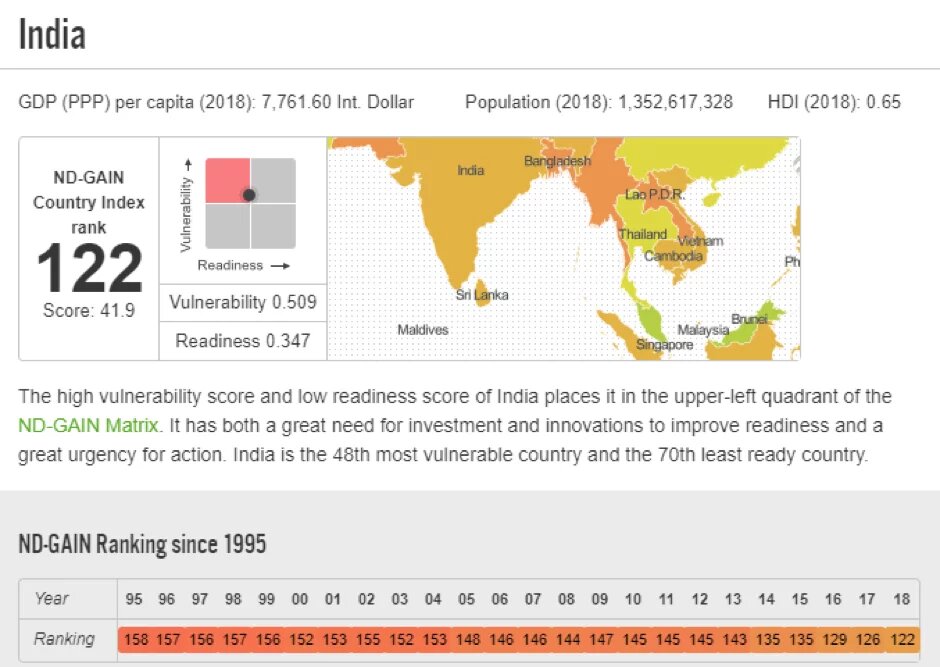

[viii]The readiness component of the index created by the Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative (ND-GAIN). ND-GAIN measures overall vulnerability by considering six life-supporting sectors – food, water, health, ecosystem service, infrastructure and human habitat. It encompasses social economic and governance indicators to assess a country’s readiness to deploy private and public investments in aid of adaptation.

[ix]Farming refers to small scale cultivation for ensuring food security and livelihoods of small and marginal farmers as opposed to ‘agriculture’ (which favours medium to large farmers).

[x]The Global Commission on Adaptation (GCA), which has a mandate of supporting action to address this challenge, focusing both at the level of infrastructure assets and systems.

[xi]GHG contribution of the land use and land use change sector is 24 per cent (excluding pre- and post- food production systems, which raise the contribution to up to 37 per cent).

[xii]160 acres of degraded forest land is being revived through a strategic mix 16 varieties of community determined species to meet livelihoods, income and cultural needs of tribal communities across four districts of Andhra Pradesh – Visakhapatnam, Vizianagaram, Srikakulum and East Godavari. Successful Efforts towards community driven mangrove restoration is yet another example.

[xiii]The Paris Agreement (Article 4, paragraph 2) requires each party to prepare, communicate and maintain successive nationally determined contributions (NDCs) that it intends to achieve.