In Asia and globally, the fight against the coronavirus has illustrated the importance of public trust in authorities, particularly when it comes to the effectiveness of various policy approaches. But what does public trust stem from? Why is it so easily lost, and what does it mean to citizens during a crisis? As the world slowly recovers and opens up, countries in Asia are continuing to grapple with new outbreaks, vaccine hesitancy and other challenges. Reflecting on the past year and a half, we take a closer look at how countries in the region have managed the relationship between the people and the state, as well as the successes – and failures – that are defining their pandemic stories.

When the coronavirus outbreak was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization and began ravaging rich nations in the West, Victor – a tour guide in his 50s living with his wife and three children on the outskirts of Tokyo – felt lucky to be in Japan.

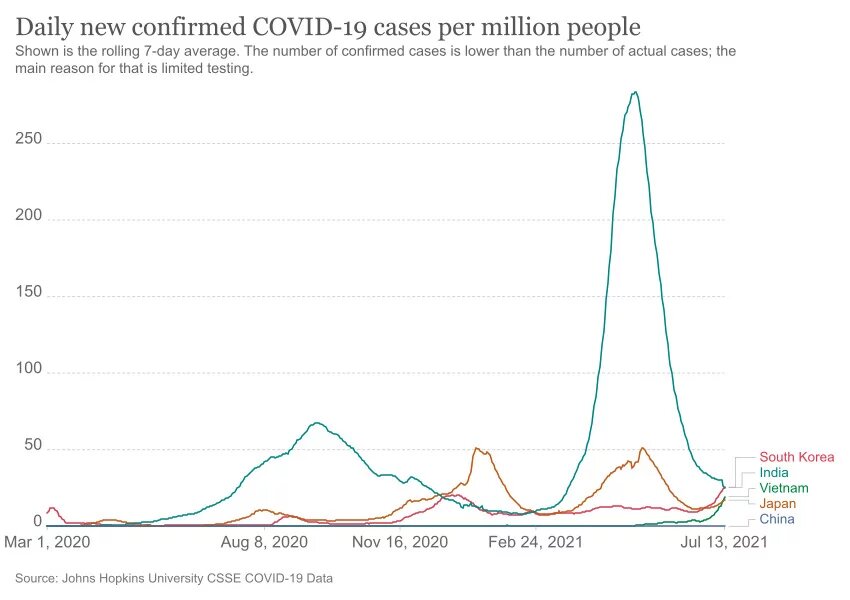

Although Japan was one of the first to identify the virus outside of China last January, the nation logged fewer than 100 daily confirmed cases until late March. Only then did the country experience its first significant wave, with cases rising to 700 daily infections in April, before dying down. During those initial months, Japan saw fewer deaths than average in Asia, despite having more elderly people per capita than any other country in the region and taking a relatively more relaxed approach to the virus.

“I felt very safe,” Victor said, explaining that there were no strict lockdowns and life was largely normal last year. He even had hope that international travel would resume quickly. “The government even had a campaign telling us to go travel and go eat.”

A low-key Olympics

A year later, things have shifted dramatically. Japan is embroiled in a fourth wave, with Covid-19 cases skyrocketing less than a month after the nation lifted its second state of emergency in March. Its vaccine rollout is also one of the most sluggish in the region, stymied by vaccine hesitancy and conservative attitudes towards regulatory approval. The vaccination rate has only picked up with developed countries since June.

An April poll by Nippon TV and Yomiuri Shimbun found that about 70% of Japanese people feel the rollout of vaccines has been too slow. Many had called for the Olympics to be cancelled, and considered it mere luck that no major outbreak had happened.

Victor’s trust in the government’s ability to handle the crisis has plummeted. He and his family have been surviving on savings for over a year. While they hope the vaccine rollout will speed up, they’re also reluctant to take the jab, citing safety concerns. “The government’s response is always delayed, and really not on point. It’s like they have no robust plan or method,” he said. “Japanese people feel less trust now.”

The situation in Japan is one that has played out in various countries in Asia since the outbreak. Although governments in the region were initially praised for their ability to contain the virus during the first months of the outbreak, many have since hit various roadblocks – challenges that have stymied progress and contributed to declining public trust in officials’ ability to manage the crisis. In many Asian countries, governments’ initial success in containing the virus caused citizens to be less fearful, and more likely to delay taking the jab.

New variants, rampant outbreaks and slow vaccination rates are threatening to put the region behind its western counterparts on the road to normalcy. In particular, governments are struggling to regain legitimacy and public trust, which experts say may have a significant impact on the efficacy of states’ pandemic policies in the coming months.

Trust is falling worldwide

Trust in governments, businesses and the media appears to be falling worldwide due to a perceived mishandling of the pandemic by leaders, according to the 2021 report of the Edelman Trust Barometer, a project that has polled thousands globally on their trust in core institutions for two decades. All the Asian countries polled in the report – including Japan, China, South Korea and India – experienced small increases in public trust between January and May of last year, before witnessing sharper declines that have continued into this year.

Despite being one of the few economies expected to report GDP growth in the age of the pandemic, China recorded the most significant year-on-year decline in general trust since the project’s inception, experiencing a 10-point drop from 82 to 72. After successfully combatting the first wave, the country saw an eight-point increase in April last year, when it eased lockdown measures and reopened businesses. Trust in the government specifically also grew by five points during that period. In the latter half of the year, however, it dropped 13 points between May 2020 and January 2021, the report said.

Following an opaque handling of the initial outbreak that curtailed public trust in authorities, China took strict measures to contain the spread, imposing severe lockdowns and pervasive surveillance measures that came under intense criticism. But as cases dropped and the West became the new epicentre of the pandemic, China eased restrictions and was able to shift the narrative of the state’s handling of the pandemic from one of initial failure to success.

So why is public trust now reportedly falling? According to researchers at Edelman, the decline “reflects an introspective Chinese mindset that takes the long view on reacting to challenges, coping with uncertainties and thinking about trust.” Others say trust is falling due to a widespread feeling in China that the state’s victories in controlling the virus have been overplayed, while the human cost has been swept under the rug. In Wuhan, the site of the outbreak, there is still anger at authorities for their delayed response to the virus, and collective memory of this trauma has continued to linger.

![]()

Mixed reactions in China

Steve Tsang, director of the SOAS China Institute, says citizens now have mixed reactions to China’s Covid-19 approach. Although the lockdowns were extreme compared to those in other countries, many do believe that “on the whole, the government handled the pandemic better than a large number of Western democratic governments,” he said. Such comparisons have been encouraged and bolstered by local media, which is tightly controlled by the government. Yet memories of the state’s initial opaque response and the heavy consequences of the national lockdowns persist, Tsang added.

Like in other parts of Asia, China’s successful containment of the virus has also contributed to a perceived lack of urgency around getting vaccinated – a trend that has hampered its vaccination rollout. Reports by various countries on the efficacy of the Chinese vaccine have been mixed, and the nation’s three major vaccine makers have yet to make available much of the peer-reviewed data from their late state trial. Such factors have led to concerns over safety and contributed to vaccine hesitancy, which I s also connected to past vaccine scares and perhaps one facet of the reported decline in trust, experts say.

India: “A lockdown buys you time”

Regionally, one country that has experienced a devastating U-turn in the fight against the virus is India. Being the new global epicentre of the pandemic in April to May, India in early May saw a peak of more than 414,000 new cases per day, a 25-fold increase since late-February; the number fell to 36,000 in mid August. As of August, the country has recorded more than 32 million infections, and the delta (B.1.617) virus variant first found in India has now spread to at least 132 other countries.

Despite being one of the world’s largest vaccine producers, India has run out of vaccines during its difficult months, as well as hospital beds and medical supplies. As the situation deteriorates, public opinion is shifting, with critics condemning the government for its complacent approach to the virus following its initial success against the outbreak. In early March, just before cases began to surge, Health Minister Harsh Vardhan declared the nation was in “the end game of the Covid-19 pandemic.”

For months, the state has also been easing lockdown restrictions, despite signs of a coming wave of infections. Many have criticised Prime Minister Narendra Modi and other politicians over their inaction, and for prioritizing politics over the pandemic by allowing reckless rallies and religious gatherings.

In India, support for Modi does not translate into trust in public institutions, according to Debasish Roy Chowdhury, researcher, journalist and co-author of an upcoming book on Indian governance. Before the current wave began, the fatality rate from the pandemic was relatively low in India and the country, like many others, was suffering from “coronavirus fatigue.” This, coupled with a nationalistic propaganda push from Modi’s administration perpetuating the idea that India had “won” against the virus, fuelled widespread complacency regarding the virus, he said.

“A lockdown buys you time to improve your infrastructure. It does not end Covid-19, it just slows the spread. India saw the lockdown itself as a solution, which was wrong,” Chowdhury said. “India did not buy enough vaccines. What you have now is an enormous vaccine shortage. It’s the reason why the rollout was very slow. Right now, there’s very low public trust in India.”

The pandemic responses in various Asian nations this past year have garnered mixed results. Yet for those who have experienced setbacks, their approaches have revealed gaps in public health infrastructure and governing practices that serve as important lessons for the region as a whole.

Some, like China, were able to contain the virus early on and emerged relatively strong with a robust economy – but are now grappling with the long-term consequences of mishandling the initial outbreak. Others, like Japan and India, appeared to fare pretty well during the first few months, only to squander those initial gains by becoming complacent and taking protracted approaches to controlling the virus.

Trust is sewn together by many threads

There have also been some relative success stories. In Vietnam for instance, centralised leadership, clear public messaging and strict enforcement of public health measures helped authorities control the virus better than some of its neighbours – and even reportedly increased public trust. Its Covid-19 figures have remained extremely low for one and a half year, until meeting its first wave in July 2021. Its national Covid-19 figures – 7,000 deaths and about 300,000 confirmed cases in August – are still low by global standards.

Although Vietnam’s tightly-controlled media landscape means that negative aspects of the state’s pandemic response are underreported, the country has still been regarded as a regional coronavirus success story. Vietnam’s economy also grew by 2.9% in 2020 and is projected to grow by 6.6% this year, according to data from the World Bank.

“I feel more trust in the government after the way they handled the pandemic. We feel so proud of what our government has done to protect us,” said Tuong Vi Nguyen, a 25-year-old Vietnamese tour guide in Hoi An who has not had a steady income since the outbreak last March.

The primary breadwinner for her family, she has spent the past year doing odd jobs while waiting for the tourism trade to restart. Despite these challenges, Nguyen says she’s emerged from the past year feeling grateful for the Vietnamese government, which she feels acted swiftly to contain the spread and prioritized public health over the economy from the get-go. Vietnam has fared better than many richer nations with more advanced healthcare capabilities, she added.

For Nguyen, a combination of luck, effective communication from the state, and people’s trust in authorities and willingness to follow the guidelines enabled the country to contain the virus. Many followed social-distancing procedures diligently, even during times when families would traditionally congregate, such as the Lunar New Year, because they were aware of the nation’s challenges and believed in the state’s policies, she said.

“Our life since last year was a big challenge. But we are still living happily and hopefully,” Nguyen said. “When people trust the government, people do what the government says. I think that is key.”

Perhaps one of the biggest lessons the pandemic has taught us is that public trust is sewn together by many threads. The pandemic trajectories of India, China, Japan and Vietnam have shown that although policy successes or failures have a short shelf-life in a fast-moving crisis, the degree to which public trust is successfully managed has long-term consequences. Faith in politicians must be backed by faith in public institutions, transparency is crucial, and while economic growth and pathways to normalcy are important goals, they cannot come at the cost of human lives.

At the end of the day, it’s not enough for states to build public trust. They must also work hard to keep it.