The paradox of Two but Not-Two

The urgency of our times

All successful social movements resemble one another, but every unsuccessful social movement is unsuccessful in its own way.

Over the years, opinion makers, activists, development agencies, political parties, non-governmental actors, have all grappled with the problem of infusing their work and social action with ‘spiritual’ values. This has now taken on a sense of urgency as we hurtle towards the climate crisis that threatens the extinction of life as we know it, and the planet becomes more and more inhospitable. There is an increasing appreciation of the view that the solution to our planetary problems do not lie merely in technological advances and inventions, but in a deeper understanding, a spiritual understanding if you may, of our relationship with nature, and our oneness with all life in the universe.

In the month of July 2022, on the idyllic campus of the Fireflies Intercultural Centre outside the IT city of Bengaluru was held the 23rd Vikalp Sangam (Alternatives Confluence) with the theme Spiritual Dimensions of Social Wellbeing and Justice.

This essay is an attempt to reflect on the presentations made at this four-day conference. It is based on my understanding and practice of Buddhism, and experience of over forty years in social action and organisation building, to offer a slightly different paradigm for thinking about the social action-spirituality duality/ dualism.

The spiritual foundation of social action

Two of the most striking statements made during these intense meetings – one from a trade union leader and the other from an academic – resonated with me powerfully!

Ashim-da, as Ashim Roy, president of the Chemical Mazdoor Panchayat, is affectionately addressed, called out the false distinction between ‘spiritual action’ and ‘social action’ in no uncertain terms. If one looks at the history of social/ political movements, all successful movements have always, or been, inspired by spiritual values, including the Bolshevik Revolution. We need look no further than the civil rights movement led by Martin Luther King Jr., the anti-apartheid freedom movement led by Nelson Mandela, or the Indian freedom struggle led by Mahatma Gandhi. In fact, all these movements are built on spiritual values to begin with, and what all these movements have in common is that they place the human person at the centre of the matrix.

Marx may have stood Hegel’s dialectics on its head, but Workers of the world unite! You have nothing to lose but your chains! is more than a political slogan. Underlying it is the spiritual value that all humans are born free, but are in chains everywhere.

Prof. John Clammer teaches Social Anthropology at the Jindal School of Liberal Arts and Humanities. In his words, paraphrased below,

“Economics does not sound like a spiritual practice, but in fact economics is a profoundly spiritual practice, because you can both reshape the world and your inner nature, because your values were shaped by the economic system.

“Spirituality is one of those strange amorphous words that disappear as soon as you try to approach it. And when you try to approach it directly, it’s not that it escapes you entirely, but you tend to fall back on those things that you are trying to avoid, like religion.

“When those two words, ‘spiritual’ and ‘material’ appear in the same sentence almost always they are opposed to one another. If you trace this historically, this has done vast damage, not only philosophically, but in extremely practical terms. A huge number of our current planetary problems, ecological damage, climate change, social and economic inequality can be traced to our economy.”

If our values are shaped by our economic system, then we should expect to find evidence of at least some societies in which different sets of values prevail and a different type of economy is dominant.

Case study – solidarity economy and social values

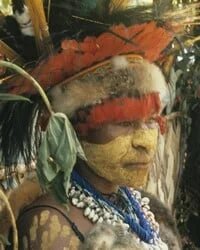

Prof. Clammer presented a case study of a group of tribes inhabiting the Goroka sub-district of the Eastern Highlands of New Guinea and known as Siane. Until the end of the Second World War in 1945, they had no direct contact with Western civilisation. The study was done by Richard F. Salisbury (1962), a Canadian anthropologist, specialising in the field of economic anthropology and anthropology of development.

Basically, the study observed the effect of the introduction of steel tools to replace their age-old stone instruments, for making arrow-heads and other items. The new technology, it appears, was introduced through their long-standing exchange relationships with neighbouring tribes, who may have got them from development-aid workers, the idea being that they could improve their productivity and efficiency, increasing their yield and profits – key markers used in the West to determine developmental growth.

A few years down the line when follow-up studies were done to evaluate the effectiveness of the new technology it was found that the yield was exactly the same as before, though the increase in productivity levels allowed them to produce the same amount in just half the time as earlier.

On inquiring into the reasons for this, it was found that the tribal communities now used the spare time thus generated to engage in their favourite activity – dancing. Obviously, the social value of communal activity such as dancing was prized higher by the community than the value of profit making or ‘capital accumulation’ as our economists would term it.

While this is certainly an example of social values trumping economic and profit-making interests, the community had yet one more explanation for their ‘irrational’ behaviour: By using the new tools, those who were more efficient would become much richer and this would introduce social inequality. So, what seems initially like an irrational decision, is actually rational, ethical and humane viewed through the lens of social values.

So, if economics is profound spiritual practice, if all social movements begin with spiritual (or at least with a moral, ethical framework) values, and if we need to move from an economy of greed and consumerism towards a solidarity economy where the best of human instincts and values trump maximisation of profit, then what is to be done?

‘Spirituality’ and ‘religion’

But before we get ahead of ourselves, we need to examine the logic often explicitly stated, behind these efforts to ‘bring’ or ‘integrate’ spirituality into social action.

At the head of the list is perhaps the confused understanding of the word spirituality itself as each individual and group strives to give it a meaning to fit within their philosophies or ideologies.

At one time or another we have all heard someone say, I’m not religious, but I am spiritual. Or, I don’t follow any particular path. But I connect with all spiritual traditions. Or, Just be true to your inner self. That is the true spirituality. So, as activists we need to get past this wishy-washy touchy-feely idea of spirituality. We may not arrive at a universally accepted definition or description, but at least at an individual level much more clarity is needed.

Now here one senses a deficit in the understanding of not just spirituality but also of religion.

Evan Thompson in his latest book, Why I Am Not a Buddhist deals with these views with great precision and clarity:

“Religions consist not just of beliefs and doctrines but also of social practices of meaning-making, including rituals and contemplative practices. Religions instil a sense of transcendence, a sensibility for that which exceeds ordinary experience.

“These forces include the desire to be part of a community organised around some sense of the sacred, or the desire to find a source of meaning that transcends the individual, or the felt need to cope with suffering, or the desire to experience deep and transformative states of contemplation.

“People use the word ‘spiritual’ because they want to emphasise transformative personal experiences apart from public religious institutions. Nevertheless, from an outside, analytical perspective informed by the history, anthropology, and sociology of religion, ‘spirituality without religion’ is really just ‘privatised, experience-oriented religion.’”

(Thompson 2020, 15-18)

Another reason for these efforts often stems from the fact that many activists and organisers experience burnout after a few years of intense political activity, coupled with the frustration that comes when there are very few tangible results to show. With the rise of populism and neo-nationalism, many governments have unabashedly resorted to oppression, with dissenting voices being jailed under draconian laws and enforcement agencies going rogue.

The general consensus here being that an infusion of spirituality would help in developing inner moral strength and courage in the face of these adverse circumstances.

In these foregoing analyses, the assumption is that there is a material-spiritual binary. And since the material approach on its own has through experience been proved inadequate or incomplete, there is an immediate need to yoke the material with the spiritual.

So how can we view this differently?

The argument that is being made by me here is that as long as the spiritual dimension is seen as something that has to be ‘integrated’ into or layered over social action, the dualism that is embedded in this view will prevent any true spiritual approach to such action, and would be reduced to mere optics.

Two but Not-Two

Zen Buddhism expresses the non-duality of the material and spiritual with the Japanese term shikishin-funi. Shiki means that which has form and colour, or physical existence, while shin means that which has neither form nor colour, or spiritual existence, such as the mind, heart, and soul. Funi is an abbreviation of nini-funi, which indicates “two (in phenomena) but not two (in essence).” This means that the material and the spiritual are two separate classes of phenomena, but non-dual (Para 5 Line 9) and indivisible in essence, because they are both aspects of the same reality.

Zen maintains that the human being must be understood as a being rooted in nature. To use the Japanese philosopher Yuasa’s (2003) phrase, it is a “being-in-nature”. This point is well portrayed in Zen’s landscape paintings wherein a human figure occupies the space of a mere dot in vast natural scenery (Section 5.3 Para 3 Line 12).

While this view of the body-mind/ material-spiritual non-duality may be satisfying to the conceptual mind of the philosopher, as agents of change and activists, how do we translate that into our practice of social action or even the somewhat narrower idea of solidarity economy?

More importantly, how do we arrive at a representation of this view that helps us arrive at a consensus-based and acceptable understanding of the idea of material action as a spiritual practice?

The mandala of social action

In most Eastern spiritual practices, a mandala is used as an object of both meditation and teaching. A mandala is a graphical or calligraphic representation of the universe of a deity or a Buddha, and in its simplest form is usually a set of concentric circles that represents the cosmos and the place of the deity and its relationship with the meditator/ sentient beings/ nature.

The central innermost circle represents the centre of one’s life. So, for instance, as a Buddhist, in the mandala of my life, I would put the Buddha at the centre of my life. As we move from the innermost to the outer circles, each layer represents the values and phenomenon in my life, from the most important, to the periphery where the lesser priorities find a place. Thus, with the Buddha as the centre, spiritual practices, perfection of generosity, compassion, wisdom, may represent the next circle. All other sentient beings will come in the next circle. Then perhaps the well-being and health of one’s body and mind, as vehicles on the path to Buddhahood and so on. Now, I have of course described this from the point of view of a Buddhist practitioner. But the same can be applied to any spiritual tradition, and the central deity/ activity/ idea and the surrounding universe be correspondingly changed.

For instance, for a capitalist or captain of industry, perhaps the innermost circle is represented by their assets, property, capital accumulation, and means of production. The next circle might represent their relationship to the powerful, the elites and media barons in their orbit. Charity, welfare of society, etc. may get pushed to a peripheral circle.

So, what should we put at the centre of the mandala of social action?

But before that, a caveat. We live in a pluralistic society and world today. There is a plurality of ethnicity, cultures, religions and certainly of spiritual traditions. To that extent, there are bound to be variations in the understanding of the structure of such a mandala. As I have already mentioned, a Buddhist may have a certain view; but this view may not be exactly in correspondence with the view of a Christian, a Muslim, a Sikh, a Jew or an indigenous Adivasi. Though these traditions would have their own understanding of material and spiritual.

It is clear from the discussions in the sections above that if human values have to dominate economic interests such as profit making, and regardless of the damage it may cause to the planet, to human beings, ever increasing production of consumer goods, we need to put nature at the centre of such a mandala.

In this paradigm, every action that is taken in the furtherance of development, well-being, social justice, means and modes of production, organisation strategies, protests, and campaigns would be determined by putting at the centre the interests of the sentient beings, (humans and all living creatures and nature itself) who are part of the community that such actions would affect. And evaluations would be made in terms of the impact these actions have on them with regard to the values and life goals and events that are meaningful to them.

For the peasant or tribal in his little hamlet, how much coal or steel the country is producing, how many kilometres of railroads and highways have been built, or how many dams have been built are of little interest. Do his children have a school to go to? If somebody falls sick, is there a health centre close by? Is there local transport easily and cheaply available to reach the school or clinic? As the paradigm changes, the indicators of well-being or development shift from GDP and per capita income to these variables that indicate the state of well-being and happiness of the people in whose name development is being justified.

If all this sounds utopian, we need to remind ourselves that this has already been implemented and is not just an idealist’s fantasy.

The phrase “gross national happiness” was first coined by the 4th King of Bhutan, King Jigme Singye Wangchuck, in 1972 when he declared, “Gross National Happiness is more important than Gross Domestic Product.” The concept implies that sustainable development should take a holistic approach towards notions of progress and give equal importance to non-economic aspects of wellbeing.

“Since then, the idea of Gross National Happiness (GNH) has influenced Bhutan’s economic and social policy, and also captured the imagination of others far beyond its borders. In creating the Gross National Happiness Index, Bhutan sought to create a measurement tool that would be useful for policymaking and create policy incentives for the government, NGOs, and businesses of Bhutan to increase GNH.

“The GNH Index (Paragraphs 1-3) includes both traditional areas of socio-economic concern such as living standards, health and education and less traditional aspects of culture and psychological wellbeing. It is a holistic reflection of the general wellbeing of the Bhutanese population rather than a subjective psychological ranking of ‘happiness’ alone.”

Perhaps we can take a leaf out of Einstein’s understanding of the space-time continuum. Einstein concluded that space and time, rather than separate and unrelated phenomena, are actually interwoven into a single continuum (called space-time) that spans multiple dimensions.

Even while acknowledging the plurality of traditions, perhaps it is time to posit a similar material-spiritual continuum.

References

Salisbury, Richard F. 1962. From stone to steel: Economic consequences and a technological change in New Guinea. Melbourne University Press.

Thompson, Evan. 2020. Why I am not a Buddhist. Kindle Edition. Yale University Press.

Yuasa, Yasuo. 2003. Shinsōshinri no genshōgakunōto (Phenomenological notes on depth-psychology) in Yuasa Yasuo Zenshū (Complete Works of Yuasa Yauso). Hakuashobō, Vol. 4.

Disclaimer: This article was prepared with the support of the Heinrich Böll Stiftung India. The views and analysis contained in the publication are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the Heinrich Böll Stiftung/and the author's affiliated institution.