Relating biological and cultural diversity for sustainable futures

What is at stake?

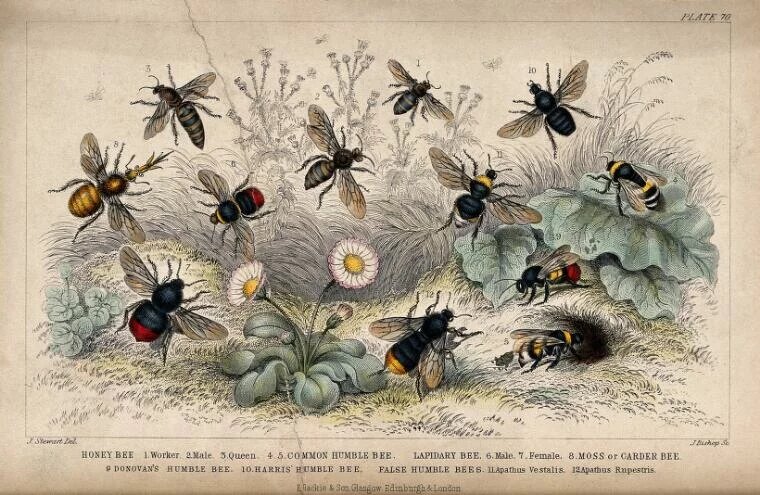

It is by now quite widely recognised that pluralism is the basis of the strength of any system. This is as true of cultural systems as it is of biological ones. It is accepted by many that the loss of biodiversity creates extreme dangers for the health of the whole planetary life-system. The loss of any species, the exact role of which in the total intricate network of biological relations is not clear and cannot always be calculated. But the fact that they are there at all in the total economy of nature suggests that they have a role to play. In some cases we can predict consequences of loss, almost always negative ones: The disappearance of the humble bee would not only deprive humans of that remarkable substance honey, but would be a catastrophe for farming in general, since bees are major pollinators. Globally we see the decline of bee species:A small but alarming signal that all is not well in the total ecology, and suggestive that humans themselves are the principle cause of this decline through the indiscriminate use of pesticides and the resulting destruction of hedgerows and wild flowers in the pursuit of industrial agriculture, depriving bees of their sources of sustenance. At the same time, globalisation has tended to the destruction or marginalisation of many indigenous cultures, their languages and the bodies of knowledge embodied in them, while, through its economic practices, hastening the destruction of natural habitats. Monocultures, whether biological or cultural, are always unstable despite (especially in the case of human political systems) their apparent strength. They are unstable precisely because they cannot cope with inevitable internal change and evolution, and because they can be easily undermined by alien agents from without – which they are not designed to anticipate or withstand, as we saw all too evidently in the outbreak of COVID-19, a pandemic almost certainly triggered by human tinkering with nature.

While in principle the desirability of protecting and sustaining both biological and cultural diversity or plurality is recognised, current practices mostly work against this, whether through processes of cultural homogenisation or the continued (usually from economic motives) erosion of biodiversity. If this is the case, then we need to look for solutions at both the policy levels and at the level of human psychology and sociology. This essay will focus on the latter.

A holistic approach: Recognising nature’s plurality

There is, as yet largely “below the radar”, a discourse emerging that goes by a variety of names: ‘One Health’, ‘Planetary Health’, or ‘Conservation Medicine’ being among the most prominent ones. What they share beneath differences of terminology is the recognition that in the current situation of global crisis, much of it ecological in nature (or associated with climate change), the notion of “health” must be a holistic one that emerges from a bio-cultural synthesis that brings into dialogue medicine (human and veterinary), ecology, social relations and culture. One clue to how this may be done resides in recent anthropological work on human-animal relations as a significant subset of the bigger issue of human-nature relations in general.

It has been recognised for centuries that humans and other animals are closely related, not only in a biological sense (we now know how much of our genetic code we share with other species, especially with the ‘higher’ apes), but in deeply psychological and spiritual ways as well. In many ways this unity has been lost, animals having become in many cases simply “beasts of burden”, food, pets, pests, or exotic creatures to be gazed at in zoos. The idea that we may be really related to animals in much more fundamental ways may come as a shock (or be rejected) by some, but, if grasped, becomes one of the major avenues through which we reestablish a sense of unity with nature that strongly resists the temptation to exploit, damage it, or treat its sentient occupants with cruelty. While this ancient wisdom has been with us for millennia, something perhaps in the current ecological crisis has encouraged anthropologists to turn their attention again to human’s relationship with animals. So too have psychologists, and we have seen the recent emergence of ideas such as that of the “nature deficit syndrome” – illnesses physical and psychic resulting from lack of exposure to nature, and the possible implications for areas as apparently remote as crime.

The results have been startling and in some ways humbling. Eduardo Kohn in his remarkable book on native Amazonians How Forests Think: Toward an Anthropology Beyond the Human has documented both the extent of interspecies communication and the recognition of profound kinship with other species on the one hand, and how the sense of self that this creates includes both an individual sense of being and the existence of a “great self” identified with nature or even the cosmos on the other. This is an exemplar of what Buddhist scholar Joanna Macy has called the ‘Ecological Self’, which she also identifies as the ground for ‘right action’ in the contemporary global crisis. The Amazonians, with their grasp of nature as a pluralistic network into which humans are embedded and which they are dependent on, have really got there first! Indian anthropologist Radhika Govindrajan in her book Animal Intimacies: Beastly Love in the Himalayas makes similar points, but extends the analysis to the possibility (indeed the reality) of love for animals, and perhaps its reciprocal expression, and the feelings of grief that can attend the loss, death or sacrifice of an animal with which one has established a special kind of relationship. While she also recognizes that there is competition between humans and animals, as when leopards prey on domestic cattle, goats and dogs, or when boars uproot carefully tended field of potatoes or other food crops, even this is seen as part of a natural web and as an aspect of things to be respected: Those creatures too have lives, hunger and families. There is not space here to review all or even a large part of the emerging literature, but other significant examples include work on human-primate relations (Agustin Fuentes and Linda D. Wolf: Primates Face to Face), on familiar domestic companions (Donna J. Haraway: The Companion Species Manifesto: Dogs, People and Significant Otherness), and on interspecies relations in general (Penelope Dransart: Living Beings: Perspectives on Interspecies Engagements).

Ethics of plurality and plurality of ethics

What is the larger significance of this trend in anthropological research? Apart from its intrinsic interest, it seems to have two main thrusts: One is to underline the idea of plurality – the idea that the biosphere is comprised of multiple species and that humans interact with it not only as animals, but through cultural means too, and to remind the same humans that they are indeed an animal species in kinship with other, but interdependent creatures. This alone might be enough: To reinforce the fact that humans are an integral part of the web of nature, and so whatever damage they do to that web will inevitably rebound on themselves. After all, a basic premise of ecology is that there is no ‘outside’ – everything remains within the total system and nothing can be removed from it; and which recognises that while that ‘system’, or perhaps better ‘organism’ is in one way a totality, that same totality is comprised of myriads of interconnecting parts, many still unknown to science.

But there are additional implications of this perception of being part of an intricate and probably unknowable plurality of beings, and I will now turn to identifying some of these. The first is ethical. Traditional philosophical ethics is largely concerned with inter-personal morality: Honesty, truth-telling, ideas of sexual morality and so forth. At most it has been extended to encompass such emerging areas as medical ethics (is ‘mercy killing’ ever justified? If one receives the transplanted organs of another person, does one still retain one’s original identity, etc.), but clearly one of the biggest issues facing humanity and other species is environmental – not only human induced climate change, but issues of waste, resource exploitation, habitat destruction and more. These are among the major issues of the day that require not only an ethical response, but also an ontological one. If we are but one species inhabiting a pluralistic ecology with other life forms, so do those forms also have rights? While the subject of animal rights, and by extension the rights of other species and features of nature (for example rivers) is now a matter of intense debate, it may also signal a remarkable form of human arrogance. In a sense simply by existing as independent creatures in no way beholden to us, all animals have intrinsic rights to existence, habitat and happiness. We seem to assume that it is we humans who alone have the power to confer ‘rights’ on other features and beings that we either had no role in creating, or to which we are responsible because we have adopted them – pets and domestic animals in particular. Being human, it is naturally hard for us to get away from an anthropocentric worldview (despite what some ‘New Agers’ may claim in allegedly identifying themselves with trees or mountains). But beyond the legalistic notion of rights, there is a much wider range of ethical discourse. Ethics should of course reflect the issues of concern in the world with which it is supposed to engage. There are sadly many such issues of course, including terrorism, the death penalty, abortion, gender rights, and a host of others. But significantly among this list must be the environment and the redefinition of our duties and responsibilities towards nature as the only actively destructive species on the planet, and destructive on a global scale. This carries with it significant ethical implications, particularly as it appears that we are the only species that has a specifically ethical consciousness – the ability to stand back from our actions and actively reflect on their consequences, for ourselves, human others and non-human others. If indeed the category of ‘sentient beings’ is extended beyond the realm of animals who clearly feel pain and pleasure (dogs and cats for instance) to other species –and there is now evidence that many varieties of animals including crabs, the octopus, ravens and many others not only feel pain, but have quite advanced consciousness, which may take forms unknowable to us with our anthropocentric model of the world – and even to plants, the range of our responsibilities and indeed kinship with nature expands enormously. Perhaps the bear is not only my ‘sister’, but perhaps the miniature Tulsi tree sitting by my desk is one also. Such considerations spill over into the nature of law, and as ‘Wild Law’ scholars such as Cormac Cullinan have pointed out, much of contemporary law is simply to do with property and its protection, and does not necessarily have much to do with justice on a wider scale. The reorientation of ethics to represent our actual location within nature is consequently a priority (and in jurisprudence too). Given the role of law in contemporary societies and its expression through hierarchies of bureaucracy in regulating almost all aspects of our urban-industrial lives, the rethinking of the very nature of law, and its philosophical foundations becomes a matter of priority, but not one much addressed. The emergence of ‘environmental law’ as a new aspect of legal practice is not the same thing at all: Here we are addressing a much deeper question of the reformulation of the very basis of the law itself, not just the application of existing forms to emerging issues. The much older and now largely abandoned idea of ‘natural law’ may unwittingly have been on to something here, even if it was rooted more in a theological conception of reality rather than an ecological one.

Recovery and imagination: Aesthetics of the good life

But critical as these aspects of absorbing a genuinely “eco-pluralist” perception of reality into our ethical thinking and legal structures, there are other fascinating implications that are only just becoming visible. These include the development of what is now being called, not ‘environmental aesthetics’ (the study of qualities of beauty in nature, as opposed simply to art), but rather ‘bio-aesthetics’, the rooting of ideas of form, harmony, beauty and colour in nature itself as the prototype and ‘mother’ of the subsequent development of aesthetic categories now associated with the arts, including such areas as dance as well as the visual arts. Such innovative thinking potentially has great implications for areas such as design, architecture and even fashion as the mechanical soullessness of our cityscapes, much contemporary art, and technological dependency as the root of alienation, nature deficit syndromes, and destructive or exploitative attitudes to nature.

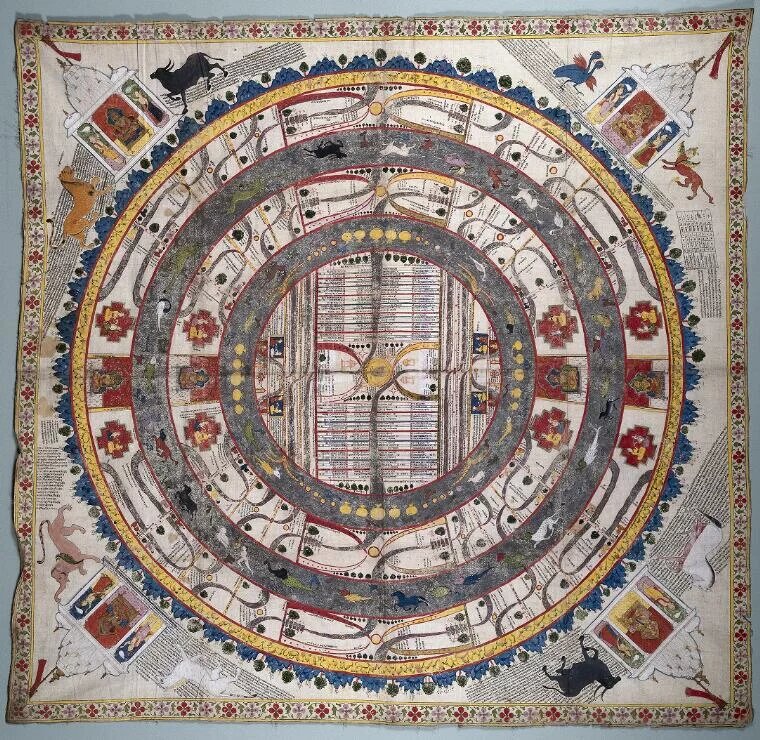

One additional important aspect of the environmental crisis is that all the major religious traditions have begun to re-examine their scriptures and practices in attempts to re-align themselves and provide appropriate responses to the ecological crisis of which they are in some cases at least partial authors. We see this is the ‘mainstream’ religions (Christianity, Islam, Judaism, Hinduism, and in Buddhism), and in religions such as the Jain faith, where deep respect for nature and the teachings of non-violence and non-killing are core, and in the reformulation of Shinto, the native religion of Japan, as a fundamentally ecological faith. Many major religions remain anthropocentric, but this shift in sensibility towards a more ecological worldview is of profound significance, given the huge numbers of adherents that each of these religions claims and their impact on thinking and behaviour. Even as anthropologists have rediscovered the significance of human-animal relationships, so too have they recently rediscovered and fundamentally re-evaluated the concept of Animism, formerly seen as a ‘primitive’ form of religious or even pre-religious belief, but now again recognised as an ancient and profound recognition of the existence of human beings among a plurality of other beings and natural forces (including rocks, trees, rivers, mountains and waterfalls) into which humans are entirely embedded.

Human beings have an odd relationship to their own history, constantly forgetting and then having to recover ancient wisdom traditions and bodies of knowledge. We seem to be in one of those moments of history when the act of recovery of one of those strands of tradition, impossible to ignore in any hunting-gathering or agricultural community, is now not only happening, but quite possibly essential to our survival. This is the concept of ‘sustainability’ that has now become a dominant theme in contemporary discourse. Science points us in the same direction: The simple recovery of the awareness, and practice based on that awareness, that we are a part of the web of nature, and, as the probably only self-conscious part, responsible for its health, maintenance and future development, a development dependent on the nurturing of the plurality and complexity that nature herself has designed as the very basis of that health.

Disclaimer: This article was prepared with the support of the Heinrich Böll Stiftung India. The views and analysis contained in the publication are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the Heinrich Böll Stiftung/and the author's affiliated institution.