Heterogeneity, homogeneity and hope

Introduction

Hinduism is a strange, large, complex, amorphous entity. Some define it as a religion, some prefer the word faith while some argue that it is, at best, a ‘philosophy’ or “a way of life”. Some others will be quick to remind that the term ‘Hinduism’ is itself a modern invention, having been used for the first time by the Bengali social reformer and scholar, Raja Ram Mohun Roy, in 1816. The roots of the term, however, are ancient, with the Greeks and Persians using ‘Hindu’ to refer to the people residing beyond the Indus/ Sindhu river. India’s erstwhile colonisers, who sought to make sense of the mind-boggling diverse religious traditions practiced in the Indian subcontinent, popularised it. What a liberal Roy was trying to give the British was not just the vocabulary to map the complex majority ‘religion’ of India, but a reformist view of it. Roy’s Hinduism had no place for oppressive practices like sati (widow burning), untouchability, polygamy, and child marriage. Christened the “Father of Indian Renaissance”, he advocated education, women’s right to inheritance and widow remarriage among other things.

But change is seldom welcomed by all. There was pushback from the conservative quarters, which resisted with counter-movements. Roy’s vision and formulation was countered with another: ‘Hindutva’. It was in 1894 that the litterateur Chandranath Basu coined the term. It found resonance with Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, a politician, writer, and activist from Maharashtra, who used it to fashion an ideology of the same name with the end goal of turning India into a Hindu Rashtra (nation). Their Hindutva, as opposed to Roy’s ‘Hinduism’, held a view of the religion that was narrow in its traditionalism. It aimed to create a “common nation (rashtra), common race (jati), and common culture or civilisation (sanskriti)” under the banner of the Hindu religion.

A war of words… Again!

India’s freedom struggle saw many freedom fighters and nationalist leaders lean on religious fervour to rouse the masses. The reification of the motherland into a Durga-like goddess, Bharat Mata, is one such example. Even progressive leaders like Gandhi and Nehru used tropes from Hinduism to write a new narrative, which irrevocably fused together nationalist and religious concepts.

The ideological battle, started nearly two centuries ago, has reached a fever pitch in the recent years, especially under the aegis of the Bharatiya Janata Party (the political arm of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh), helmed by prime minister Narendra Modi. Hindutva, once a fringe ideology, has become mainstream, while liberals struggle to uphold the vision of Roy’s Hinduism. The purveyors of Hindutva have pervasively used the mythical figures of Lord Rama and Hanumana, the temple site of Ayodhya, the idea of cow protectionism, and the practice of vegetarianism in political/ electoral contexts to promote an idea of Hindu universalism. Additionally, legislative tactics like beef bans, anti-conversion, and citizenship laws, are a perfect recipe to intimidate India’s religious minorities, especially Muslims.

Such projections of a monolithic Hindu identity, coupled with hatred, violence and bigotry has been ringing alarm bells in the liberal quarters. There have been an increasing number of Hindu liberal voices, who have been pushing back against these propagandist overtures, making a case for ‘real’ Hinduism, which they say is more tolerant, inclusive, diverse, and plural. In their bid to distance themselves from right-wing ideas, some have even claimed that ‘Hinduism’ is a colonial construct. But as renowned political commentator and academic Pratap Bhanu Mehta recently pointed out in a column, that this is a fallacious view that does not take into cognisance the broader ontological frameworks and pre-modern sources of history.

The not-so-innocent history of Hinduism

The Left-liberal claim of Hinduism’s catholicity is not without merit, and warrants consideration. However, we shall come to it later in this essay, contending first with Hinduism’s not-so-innocent history. Going beyond the “Hinduism-as-a-colonial-construct” thesis, Hinduism’s inherent paradoxes are important to recognise for those who seek to defend it.

Mehta is correct in criticising the rampant ignorance around India’s pre-modern historical sources and cultural width, as reflected in commonly held mis-beliefs about India being a peace-loving country, which was never first to start a war – a notion publicly flaunted by the Indian Prime Minister. Hindu Chola kings are known to have colonised Sri Lanka, the Maldives, and parts of South Asia in the 11th century CE, and not to forget the countless instances of in-fighting between the kingdoms.

Far greater than the political and military violence of any Hindu ruler, is the violence inherent in the structural processes of Hinduism. Indubitably, Hinduism’s fatal flaw, the caste system, can be traced back to its Vedic origins. While its beneficiaries will often gloss over the concepts of jati (caste communities) and varnashrama (occupation and life-stage classification), justifying its origins and rationalising its functions, it is an exploitative anti-humanitarian system.

Take for example the endless instances of caste violence that continue even in the 21st century. It could range anywhere from upper caste Hindus beating up so-called lower caste Dalits for ‘minor’ transgressions like touching or drinking from “upper caste water pots”, to downright killing them for ‘major’ offences like marrying people from the Savarna community. In the not-so-direct instances, people from backward communities rarely have access to housing in privileged communities, access to education or healthcare, or to positions of institutional power. Casual forms of discrimination are common in Savarna households, where segregation is manifest in the way lower caste domestic workers are given separate utensils or toilets to use.

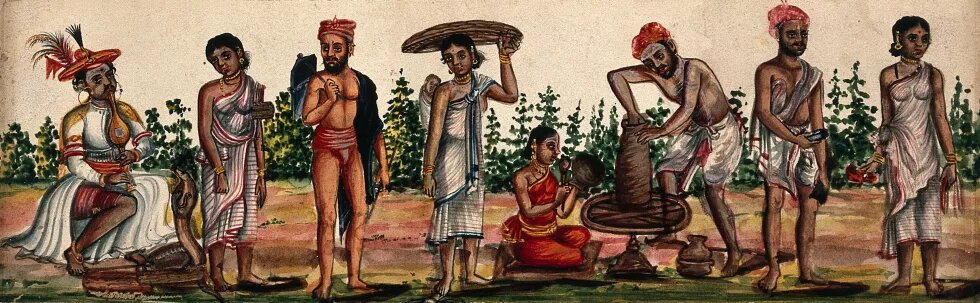

Savarnas are Hindus who belong to the four-fold caste tier, starting with Brahmins at the top, followed by Kshatriyas, Vaishyas, and Shudras. Traditionally, Brahmins were the priests and intelligentsia; Kshatriyas, the rulers and administrators; Vaishyas, traders and craftsmen; and Shudras, menial labourers. Power was concentrated in the hands of the top three castes with Shudras receiving the short end of the stick. Perhaps their only consolation was belonging to the caste tier. A large mass of people, who got an even rawer deal, existed outside the Varna fold, which made them Avarna meaning ‘without Varna’, and were treated as untouchables. These masses are now referred to as Bahujans, Dalits, and Adivasis (DBA), and are deemed ‘Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes’ (SC and ST) by the Government of India.

The oppression faced by the lower or non-caste people at the hands of the upper caste Hindus has been a constant, indeed, foundational feature of Hinduism. The upper caste Hindus, who comprise only 30 per cent of the population, have created such structures of power and inequity over the centuries that Dalits continue to face all manner of violence.

The basis for such oppression can be found in Hinduism’s oldest foundational texts – the Vedas. A creation story in the Purusha Sukta (the hymn of the Cosmic Man) of the Rig Veda states how the Brahmins were born out of the forehead (signifying human intelligence) of the cosmic man or creator, the Kshatriyas from his arms (signifying valour), the Vaishyas from his abdomen/ thighs (signifying hunger and carnality), and the Shudras from his feet (signifying labour and lack of hygiene). The Dalits or ati-Shudras do not find place in this myth, effectively designating them ‘unborn’, and hence having no place in civil society. The unquestionable hierarchy in this story has been one of the powerful ways in which centuries of discrimination has been justified, although caste apologists like to rationalise this as demarcation of hereditary professions, and allege that the liberal lens misconstrues the premise.

There is ample evidence in Vedic literature itself to confirm discriminatory attitudes of Brahmins towards ‘outsider’ communities, even if they may not have been labelled ‘caste’ in the modern sense. The running trope of “us versus them” in Vedic society was that of Aryas versus Dasas, with the Aryas being those that adhered to the Vedic sacrificial religion and the Dasas or Dasyus being those that didn’t. Max Mueller and many scholars after him believed that the latter referred to the indigenous people of India (Müller, 1847, 339). It becomes amply clear from the Rig Veda that there was constant and bitter rivalry between the two communities. Many hymns are addressed to the king of gods, Indra, invoking him to lead the charge against and destroy the dasyus. For example:

अकर्मादस्युरभिनोअमन्तुरन्यव्रतोअमानुषः।त्वंतस्यामित्रहन्वधर्दासस्यदम्भय॥८॥ [Rig Veda 10.22.8]

[Translation by H. H. Wilson]

The Dasyu practising no religious rites, not knowing us thoroughly, following other observances, obeying no human laws, Baffle, destroyer of enemies [Indra], the weapon of that Dasa.

The need to tame ‘the enemy’ is further reflected in mythological stories and legends. Whether through tales of the Hindu god Rama’s epic journey through India (to Lanka) or through those of sage Agastya’s spiritual conquests in southern India, the trope of Brahminisation emerges. Alternatively referred to as Sanskritisation, it refers to the historical process through which local Indian religious traditions became aligned to or absorbed into the Brahminical tradition.

An example of Sanskritisation is the formation of the ‘Shiva family’, wherein local deities such as Kartikeya and Ganesha are turned into the sons of Shiva and Parvati through Puranic stories. Similarly, countless local goddesses – the grama devis and vana devis (village and forest goddesses) – were declared a version of the Hindu goddess Parvati, and consequently Shiva’s wife through marriage. Shiva himself was a wild, borderline deity of the Vedic pantheon, but was given a major facelift in his Puranic avatar. He was assigned a place in the important Hindu trinity of Brahma-Vishnu-Mahesh (Shiva), replacing the principal Vedic gods like Indra, Agni, Vayu and Varuna. Another incredible example of Puranic Sanskritisation is the claiming of Gautama Buddha as an avatara or incarnation of the Hindu god, Vishnu. Thus, in complete oblivion of the historical fact that Buddhism was a rival religion, it rendered Buddhism into a form of Hinduism. The composition of the Puranas between the third and the 10th centuries CE helped grow and consolidate Hinduism into the form we know today, and was instrumental in Sanskritisation.

Subsummation was a key strategy by which numerous Adivasi (meaning original dwellers) and other indigenous tribes were inducted into the Hindu fold, thrusting upon them a Hindu identity, but keeping them at the periphery by treating them as outcastes. After centuries of such indignity, tribals in many parts of India are beginning to voice their protest, seeking to break away from the Hindu identity. It is evident in slightly larger political movements such as the Sarna Movement of Jharkhand, Odisha, Assam, Bihar, and West Bengal, where there is demand for the implementation of the Sarna code under which tribals will have to right to self-identify as people of the Sarna religion (a nature-based religion) in the upcoming census. Other instances are where tribal people worship the ‘demon’ Mahishasura instead of the goddess Durga during Navratri by contending that the so-called demon or asura was their valorous king, and they would rather worship him than the Hindu goddess. It is their attempt to challenge the good versus evil dichotomy, which taints everything that isn’t Hindu as ‘evil’.

There have been consistent attempts to quell these rising voices of dissent, and even attempts at ghar wapsi (return home) – a fundamentalist invention of bringing people back into their ‘original’ faith, often, taking the form of forced (re)conversions of Muslims, Buddhists or Christians into Hinduism, in alignment with the popular proclamation that the latter is the primordial faith or Sanatana Dharma. This is an ironic countermeasure by those very people who object to conversions by Christians or Muslims. The recent Supreme Court judgement that allows for ‘economic criteria’ as a basis for reservations regardless of social caste origin has been questioned by many commentators for failing to uphold constitutional values meant to end the perpetuation of discrimination against SCs, STs and other backward classes.

Such coercive practices and extremist interpretations, forms of violence such as in the name of cow vigilantism or love jihad, as well as superstition-related malpractices are truths about Hinduism that must be contended with. Like any other religion, it comes with its share of flaws.

H for Hinduism, H for Hope

However, Hinduism also offers hope. It is imbued with features that make room for positive change and growth. Subsummation, the very feature that was (wrongly) used to undermine and absorb other cultures, is also Hinduism’s strength and herein lies Hinduism’s greatest paradox.

In fact, adaptability is one of Hinduism’s strongest suits, making it the world’s oldest living religion. One of its greatest advantages is not having a central scripture, pope, or church. With its multitudes of traditions, seers, and sects there is no one way to be a Hindu. Hinduism is not a monolithic but pluralistic faith; there are many Hinduisms!

Such decentralisation has meant religious power is diffused, even if it is wielded by the priestly Brahmin class. Further, the historical precedent set by the Bhakti saints in medieval India offers templates of not just breaking away from Brahminical hegemony but forming of a more inclusive, syncretic, and harmonious society.

Hinduism lends itself easily to pluralism by allowing many paths towards the singular spiritual truth, as reflected in the Upanishadic phrase: 'ekam sat viprabahudhavadanti' (Truth is one, the wise perceive it differently). For centuries, it has survived numerous internal and external conflicts and is going strong. Hindus continue to be Hindus in a variety of ways, through the languages they speak, the ways they celebrate festivals, the foods they eat, the arts they practice, and the gods they worship. Each year, storytellers retell and re-imagine stories from Hindu myths and we are none the poorer. Hinduism continues to rebuild itself upon its own edifice.

Even as Hindu fundamentalism rears its ugly head, counter-movements in the form of organisations like Hindus for Human Rights are beginning to appear to remind us of the saner, most compassionate voices among us. It is time to continue shining the light on what is good about this vast, wonderful, and eclectic religion, and remember that it is from a Hindu Upanishad that we have the maxim of Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam (the world is one family).

References

Press Trust of India. 2016. India has never attacked any country, is not hungry for any territory, says PM Modi. The Times of India.

Forty Christians forcibly re-converted in India. International Christian Concern. 2022. Persecution.org.

Bhanu Mehta, Pratap. 2022. Why it’s wrong to say that Hinduism is a product of colonialism. The Indian Express.

Chaubey, Santosh. 2021. Journey of Hindutva in RSS: How the Sangh's definition of the concept has evolved. News 18.

Chauhan, K S. 2022. Failing the constitution. The Indian Express.

Müller, Max. 1847. On the relation of Bengali to the Aryan and aboriginal languages of India, Report of British Association.

Vishwadeepak. 2021. RSS-BJP despised in Chandranath Basu’s birthplace, who coined term ‘Hindutva’ before Savarkar popularised it. National Herald.

Disclaimer: This article was prepared with the support of the Heinrich Böll Stiftung India. The views and analysis contained in the publication are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the Heinrich Böll Stiftung/and the author's affiliated institution.