India’s political ambition for Global South leadership emanates from an enduring commitment to self-determination, multilateralism, and a quest for a more equitable global order.

Key messages:

-

India’s pursuit of leadership in the Global South is anchored in its historical experience of non-alignment and its growing economic weight, using these to strengthen strategic autonomy and advance a multipolar order aligned with its values and interests.

-

Emphasising cooperation over competition, India frames its engagement as amplifying the collective voice of the Global South, underscoring sovereignty, agency, and equitable representation rather than a top-down model of leadership.

-

India’s initiatives in development cooperation — from digital public infrastructure and renewable energy to vaccine diplomacy — provide important public goods and showcase alternative pathways for growth, though their scale remains modest compared to China’s infrastructure-led model.

-

Despite convening summits and drawing on its democratic credentials, India’s influence is tempered by the diversity of the Global South, where not all states share its political values and where symbolic actions must be matched by more substantive outcomes.

-

In an era of heightened contestation marked by US unilateralism and China’s material dominance, India seeks to position itself as a bridge-builder and stabiliser, while facing the challenge of matching expectations with deliverable capacity.

Introduction

The term Global South has not only acquired a profound political connotation in present day geopolitics, but has also put the spotlight on the leadership of such a diverse and unstructured group. In a time of increased great power competition and geo-economic contestation, it has brought focus on political groupings and leadership in the international arena. It is in this context that the Global South seeks a voice and support for issues ranging from climate justice, debt sustainability, access to technology and reformed multilateral institutions. India’s aspiration to lead the Global South is consequential within the backdrop of an increasingly fragmented multilateral and contested global order. Posited beyond a rhetorical argument, India’s vision of leading the Global South is embedded in its historical legacy of Non-Alignment, and an evolving strategic imperative, given the rise of its own global stature.

India’s aspiration to lead the Global South is consequential within the backdrop of an increasingly fragmented multilateral and contested global order.

India has always sought a position on the global stage, from the time of the first Prime Minister Nehru, who led the country’s claim with power of the moral ideas that the country stood for at the time of its independence. This quest for leadership has been greatly buoyed with a robust economy that in 2025 is the 5th largest in the world, giving it more confidence in projecting its claims. For India, this leadership role offers it a platform to consolidate its strategic autonomy and emerge beyond the category of being merely a swing state in a growing geopolitical contestation. By projecting itself as a “Vishwa Mitra” (friend of the world), India seeks to strengthen the collective voice, enable greater agency and ensure an equitable representation for the developing countries in the global arena. In doing so, it also seeks to enhance its own influence and shape a multipolar world order that reflects its own values and interests. It is in this context that this article examines the political, economic and strategic opportunities and challenges that shape India’s aspiration for leadership of the Global South within the context of the growing geopolitical contestation and realignment of power.

Enhancing the Collective Voice though Political Engagement

India’s political ambition for Global South leadership emanates from an enduring commitment to self-determination, multilateralism, and a quest for a more equitable global order. The journey from the Bandung Conference in 1955 for a newly independent India led it to create and lead the Non-Aligned Movement, while advocating sovereignty and the pursuit of independent foreign policy choices for the newly decolonised nations. Having navigated the Cold War, India’s foreign policy has evolved into adopting strategic autonomy and multi-alignment while offering developing nations an alternative from the rigidities of great power blocs.

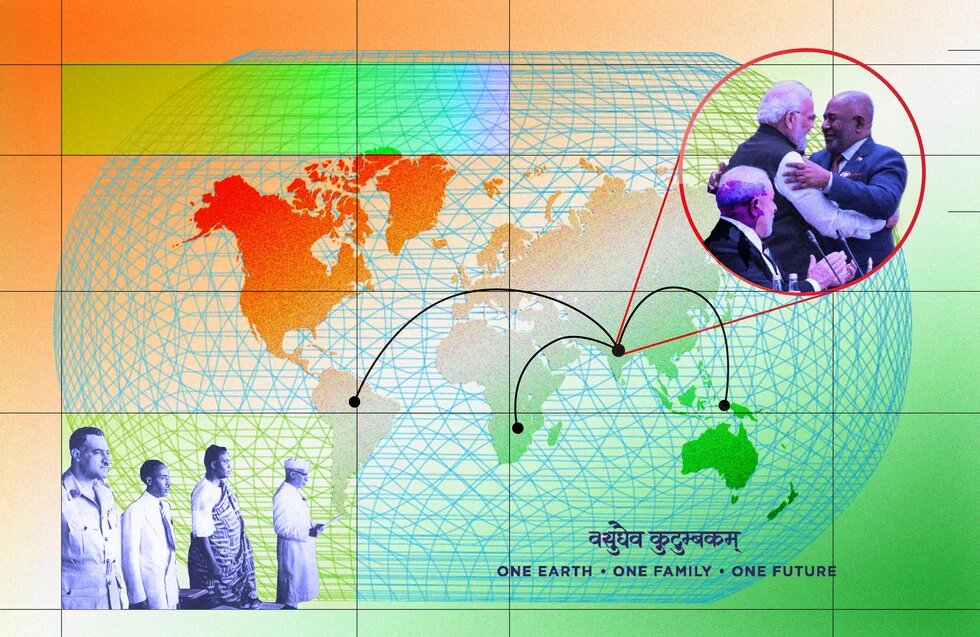

From India’s perspective, the global governance institutions created in the Cold War period do not reflect the contemporary power diffusion and the growing influence of the emerging powers. Thus, institutions like the United Nations (UN), its Security Council (UNSC), International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank and World Health Organisation (WHO) reflect a bygone era of power and there has been minimal action towards reform. India’s strident push for a permanent seat in the UNSC is framed not just as national aspiration, but as a critical step to give a larger voice to the Global South, which constitutes 85 percent of the world population and contributes nearly 40 percent of world GDP. Leadership of such a large group would be an asset to any foreign policy, and this was visible during India’s G20 presidency in 2023, where it served as a crucial platform to operationalise this vision. Due to the consistent efforts of New Delhi, the G20 was expanded to include the African Union as a permanent member and it was evidence of India’s strong interest convergence with advocacy. New Delhi convened the first ‘Voice of the Global South Summit” in 2023, which was attended by 125 countries, with the notable absence of China, which was not invited. If the summit demonstrated India’s commitment to engage the Global South not as a passive recipient of aid or policy prescriptions, but as an active and indispensable partner to reshape the global agenda, it also highlighted New Delhi skilfully using its historical legacy for positioning itself as leader in the current context. The G20 was also a political opportunity to display the material developments and the social transformation as evidence of what India had internally achieved. There was much symbolism in the actions, and although India did not offer a direct challenge to China, it showcased itself as an alternative partner of engagement.

For western critics, and especially China, which considered its non-invitation as a strategic exclusion to thwart its own leadership claims, the summit did not translate either into acquiesce of India’s leadership or showcase capacity to make a difference on the international arena. India adopted the slogan of “Vasudev Kutumbakam” (one earth, one family, one future) for the G20 Summit, and carefully constructed the image and positioned Brand India against the other Asian giant, as an inclusive and non-confrontational leader. By hosting two more summits in November 2023 and August 2024, it sought to reinforce its image and commitment to a collaborative and consensus driven model of engagement. The three summits have been strongly projected by New Delhi to showcase its convening power and the participation of the leaders has been used to strengthen its credentials to lead the Global South. However, there are contestations not only between the Asian countries India and China to assume this role, but also in other regions of the Global South. As the G20 Summit moved from India to Brazil and South Africa, one can observe similar trends of assertion and claim to leadership at least for their respective regions if not for the entire Global South.

For any country to project power and build influence, it has to deploy a strategy based on the combination of ideational and material power. Although the world’s 5th largest economy, India has not been able to compete with China in its use of material resources. Consequently, the political strategy employed by India to project and advance its ideas has been through greater diplomatic engagement such as the G20 and the BRICS, IBSA and SCO summits. The recent ramping up in the leadership game is also connected to the personal effort by Prime Minister Narendra Modi to connect Brand India with himself through his extensive diplomatic outreach.

Revisioning South- South Economic Cooperation

Although this rediscovered leadership of the south is in tandem with India’s own fast paced economic growth, it is however very nuanced reflecting the challenging realities of navigating heightened geopolitical contestation amidst an emerging multipolar world and strong economic consequences that also impact the global supply chain. India’s economic vision for the Global South is underpinned by a shared understanding of development challenges and a commitment to enhancing South-South Cooperation. India’s economic support to the Global South countries has evolved from its initial efforts in capacity building in the 1960s through the Indian Technical Economic Cooperation programme, which has been the key instrument for training, scholarship and expert assistance, and disaster relief delivery, thus building human capital. This had produced a positive perception about India in many Asian and African countries during the Cold War period. However, given the limited economic resources invested by India, and the strong presence of the traditional donors, New Delhi’s influence was restricted to building a positive image and investment in human capital.

As an important pillar of India’s external economic policy, this engagement witnessed a coming of age in the last decade since the adoption of the Global Partnership for Effective Development Cooperation (GPEDC) at the Busan Summit in 2011. The partnership principles are in sync with India’s own approach that prioritises collaboration over competition and more importantly offers solutions from its own development experience. India’s economic growth and transformation of the world’s largest population with apolitical mandate embedded in democracy has meant navigating the intricate challenges between poverty, climate vulnerability, food security, energy access while managing socio-economic upliftment amidst strong social stratification. If the India story holds lessons for the developing world, however, the Chinese also offer their own model to many countries in Africa and Asia that may be more amenable to non-democratic countries.

The rapid growth of the Indian economy in the last few decades, racing ahead from the 10th largest economy in 2014 to the 5th largest in 2025, and the technological breakthrough along with the enhancement of digital public infrastructure, has brought a new dimension to its foreign policy engagement reflected also in its development and economic activities with the countries of the Global South. In a major support to the Global South countries during the Covid-19 pandemic, India showed leadership in global public health and undertook “Vaccine Maitri” (vaccine friendship) and supplied Indian developed and produced vaccine to countries in Africa at a much affordable price, while the West displayed vaccine nationalism. Similarly, its development cooperation initiatives now encompass areas of infrastructure development and connectivity and also promoting renewable energy solutions through the International Solar Alliance.

India’s remarkable success in using technology in designing digital public infrastructure has contributed to financial inclusion, efficiency in service delivery, innovation and connectivity within the country. Actively promoted by India as a tool for socio-economic upliftment and empowerment, it has been adopted by six African countries (Ethiopia, Morocco, Angola, Sierra Leone, Guinea and Zambia), while Rwanda and Ghana are in discussion to implement similar payment platforms. This cost-effective model of digital connectivity can be viewed as a third way towards creating a digital non-alignment. In the current contested geopolitical landscape, economic policies and trade have become weaponised and trade disruption today poses a major threat to economic security of countries. India’s strategy has focused on offering “Make in India” as an active component to diversify supply chains and enable a de-risking strategy against China, building economic resilience and equitable access to resources as a viable alternative.

This cost-effective model of digital connectivity can be viewed as a third way towards creating a digital non-alignment.

Compared to China, Indian capacity for development support has been limited in both scale and size. China’s Belt and Road Initiative, which is a state backed initiative launched more than a decade ago, is truly a global endeavour in terms of the number of countries, projects and capital invested by Beijing since 2013 to scale up infrastructure development at an unimaginable scale. BRI has enabled China to project power and wield influence at a level far beyond the financial and political reach of India and has even posed a challenge to the western countries that have long been present in these countries. Although designed to deliver large scale infrastructure projects, these have also functioned as a catalyst for major economic instability. African countries have faced higher vulnerability and many including Angola, Congo, Ethiopia, Kenya, Nigeria and Sudan have become overstretched by their economic commitments in the BRI. The Chinese projects have been characterised by opaque financial terms and immense debt obligations in many countries, leading to dire economic crises for the participating states, who have been confronted by compromised economic sovereignty and long-term economic instability.

In stark contrast to China, India’s success in the field of economic diplomacy has been limited. The Indian private sector has stepped in with projects and investment in manufacturing that is no match to the Chinese economic engagement. India thus needs to scale up with speed and with technology for enhancing a more meaningful economic cooperation at the South-South level.

Shaping Indian Foreign Policy towards the Global South in a Contested World

The Indian foreign policy has evolved from non-alignment during the Cold War to seeking relations with all countries, displaying a new approach of multi- alignment. In addition, it has also sought to enhance its “strategic autonomy”, so that it can effectively prioritise its national interest. Thus, in a rapidly evolving geopolitical contested arena, India’s claim to lead the Global South has many strategic purposes, especially in the context of the rise of other emerging powers. Drawing upon its historical legacy of non-alignment to foster solidarity and cooperation, India has also sought to position itself as a bridge between the south and the north.

India has consciously sought to strengthen ties with the Global South countries as a strategy to balance and hedge against the influence of others, especially China. One example of this is to expand its diplomatic and strategic footprint by strengthening its institutional presence, but also through high level visits of the Prime Minister and President. Second, through its neutral stance towards the Ukraine war, India sought to offer a counter-narrative to the binary choice of bloc politics and, through its actions, positioned itself as an actor that could engage all parties.

However, the rules and the role of political engagement have shifted dramatically in the last two decades. Presence has to translate into more than having an embassy in all countries, where India with its small diplomatic staff often is unable to provide a bandwidth for engagement. Thus, in the absence of such a capacity, a more sophisticated approach is clearly required. A case in point was the G20 Summit in 2023, wherein India transformed a once in a two-decade leadership moment to a repositioning of Brand India to the invited audience by showcasing the material progress and the new development story.

India strongly believes that a multipolar world is truly reflective and more aligned with the power diffusion underway and does not consider it to be producing instability. With its steadily rising economic power as the 5th largest economy, it is an economic pole and has sought to use this to represent the concerns of the Global South across global fora. Simultaneously, it is strongly invested in multilateralism, seeking to expand the circle of global decision-making in which the voices of the Global South get a genuine representation. India’s reformist outlook to the global institutions has found resonance with other south leaders such as Brazil and South Africa, but not with everyone and this reveals that the gap between convening and creating a following depends on factors more than political actions. India’s ideational power and example of a democracy have not automatically translated into influence, given that many countries of the Global South are not democracies and do not place the same importance on such political values.

An important element of leadership is to engage and build regional stability. With the growing geopolitical contestation especially in the Indo-Pacific region, India has a compelling interest in stability and maritime security in this region. The growing Chinese engagement, especially in South Asia and the Indian Ocean, has received a strong pushback from India as it has increased its engagement with the Global South countries in this context. India’s policy of maritime engagement in the Indian Ocean region through Security and Growth for all in the Region (SAGAR) launched in 2015 has since been upgraded to the MAHASAGAR that expands to include economic and geopolitical concerns. In a major strategic push, a clear pivot to Africa and strengthening the engagement with the Western Indian Ocean are evident. The Indian Navy has expanded action to combat and counter non-traditional threats like Somali piracy, and check illegal fishing, drug trafficking in and around the Gulf of Aden, Mozambique and the Red Sea. Nine African countries are members of the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA), which India will chair later this year. India has increased investment in building maritime infrastructure, sharing maritime domain knowledge and the more recent Africa-India Key Maritime Engagement (AIKEYME) in April this year, a large-scale multilateral maritime exercise having 11 countries co-hosted with Tanzania, signalled intentionality to claim leadership and expand benefits to partner African countries. The Indian policy has also sought to do capacity building in areas of humanitarian assistance and disaster relief, while contributing to secure the global maritime commons for trade and navigation.

Conclusion

The Global South as an idea and the solidarity within are two separate aspects, given the extreme heterogeneity among the countries. India’s vision for leadership of the Global South is rooted in a profound understanding of the changing geopolitical landscape, shaped by a mix of political ideas, economic necessities and strategic considerations. The sharp impact of the Trump administration policies that has undermined partnerships, eroded international institutional engagements and imposed cost on all countries by weaponizing tariffs has brought the focus back to leadership at the global and regional level. It has confirmed the dominant role that the US will play in the international arena, irrespective of who aspires to lead the Global South. The US remains the undisputed leader and has shown its preference to work bilaterally with countries, bypassing institutions.

India has showcased through its own engagement that despite a strategic partnership with the US, it has not allowed anyone to dictate its foreign policy choice of relations with other states. Notwithstanding this schism in its relation to the US, India has adopted a nuanced approach to the countries of the Global South that seeks to empower and not dominate, to collaborate and not dictate and to create an inclusive network and not offer competing polarised blocs. In an age of growing geopolitical and geo-economic contestation, with the major powers trying to exert influence and act unilaterally, India offers an alternate model based on a historical perspective of collective action.

India has adopted a nuanced approach to the countries of the Global South that seeks to empower and not dominate, to collaborate and not dictate.

However, the ability to convert engagement to growing influence and political preference on part of the leadership of the various south countries has been better played by China, which has not been obstructed by insufficient material resources. China has been sceptical of India’s leadership claims and has sought to contest it at multiple levels, even though both cooperate across certain multilateral formations like the BRICS and SCO. If India seeks to represent the collective interest of the Global South, it needs to show more evidence of inclusion of the south in its activities by investing more in deliverable results and not symbolic actions. The maritime domain has produced more pronounced output. Today, India positions itself as a crucial bridge builder and responsible actor committed to a more just, resilient and multipolar global order that stems from its own philosophy of “Vasudeva Kutumbakam” – the idea that the world is one family. As the global order becomes increasingly fragmented and power diffuses at multiple levels, India is rebranding itself as a prospective leader of the Global South working to build new solidarity and collective action through the renewed framework of the South–South Cooperation. However, the leadership role also presents numerous challenges for India. It would need to institutionalise its influence if it wants more of a political visibility and build consensus among such a diverse group. However, its biggest challenge is to match the Chinese scale and size of economic investment that creates a mismatch between role definition, expectation and delivery.

In more ways than one, there is direct and indirect contestation based on capacity, political engagement and material power between India and China and other actors for the role of leading the Global South. While India has drawn on ideational resources in the past and now uses its growing economic power to present itself as a leader, China has used material assets first and now brings elements of ideational power into the mix to position its leadership claims, as recently showcased through the successful SCO summit. Evidently, there are many claimants and contestations to leadership of the Global South and given the range of political and economic and security issues, there is no clear, defined one leader for such a heterogeneous group, where building consensus is the most difficult task. For India, the Global South is one category of engagement in its foreign policy to be balanced by its other competing priorities and relations with the West.