The “rise” of regional political parties seems to be an eternal theme on the Indian political scene. Indeed, it has become a standard trope of Indian political analysis to deluge readers with excited descriptions of India’s fragmented party system and the multiplicity of local parties that appear to crop up like weeds after a monsoon rain. Observers also like to note the continued decline of India’s two genuinely national parties, the Indian National Congress and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

There is, of course, a kernel of truth to these claims. Many of the leading power brokers in contemporary Indian politics hail from regional parties—such as former chief ministers of Uttar Pradesh Mulayam Singh Yadav and Mayawati as well as Chief Minister of West Bengal Mamata Banerjee. Looking at them, it is not hard to believe that times have changed.

There is plenty of hard data to back up this sentiment. The exponential increase in the number of parties contesting elections, particularly over the past two decades, and the shrinking margins of victory in parliamentary elections are direct results of the emergence of new regional power centers. At last count, the fifteenth Lok Sabha, the lower house of parliament, boasted 38 parties, all but two of which are largely ethnic, regional, or subregional enterprises.

The rise of regional parties has indisputably transformed the very nature of electoral politics in India. For the foreseeable future, it is unimaginable that a single party could form the government in New Delhi—a testament enough to this tectonic shift.

But whether regional parties will be able to wrest greater control over the shape of governance in the capital and in India’s states remains an open question. There is an unfortunate, unswerving progression to the conventional narrative, which treats regional parties as constantly on the rise, acquiring greater political space. In fact, there are a number of trends that indicate regional parties may not be the juggernauts many observers make them out to be.

Four myths about the “rise” of regional parties overstate the on-the-ground realities.

Myth: Regional Parties Undermine National Parties

A common myth about regional parties is that their rise, by definition, has eroded—and continues to erode—the stature of national parties. But in reality, after a period of unprecedented growth in the standing of regional parties during the late 1980s and early 1990s, the pattern of electoral competition at the national level has achieved a surprisingly stable balance of power.

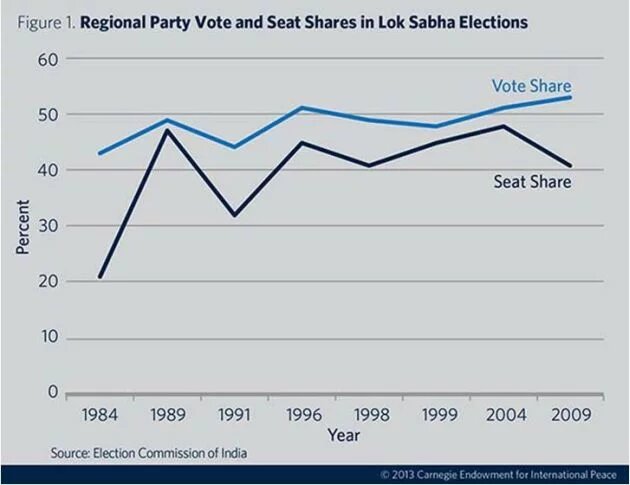

The aggregate vote shares won by the two truly national parties and “the rest,” meaning primarily regional parties, in the past five elections illustrate strikingly that the respective popularity of these two groups is in a rather steady holding pattern. The share of votes won by regional parties cracked the 50 percent mark for the first time in 1996. Then the engine sputtered somewhat. By 1999, vote share of regional parties had dipped to 48 percent. By 2004, their vote share crept back up to 51 percent, the same level it had been eight years earlier, before modestly rising again in the 2009 elections.

What’s more, the doomsday scenario in which the rise of regional players directly threatens the status of national players overlooks the possibility that regional parties can also hurt one another. In India’s winner-take-all electoral system, where victories are possible with a small minority of votes in any given constituency, increasing levels of political competition have led to a greater fragmentation of the vote. In 2009, for instance, less than a quarter of electoral districts were won with a majority of votes. The net result has often been regional parties crowding out other rival regional parties. See, for example, the electoral impact of the Maharashtra Navnirman Sena party, which took votes away from its key regional rival, the Shiv Sena, in the state of Maharashtra. And competition between upstart and established Telugu regional parties in Andhra Pradesh redounded to the benefit of the Congress Party.

The increasingly fragmented vote has affected the share of seats won by regional parties in Lok Sabha elections. At present, regional parties occupy 41 percent of the seats—the same share they held in 1998. This is actually a decline from the two previous election cycles. Regional parties’ vote share reached its highest level in 2009 (53 percent), but the share of seats allocated to regional parties declined because of fragmentation , suggesting that the proliferation of regional parties risks cannibalizing the “non-national party” vote share.

One way in which regional parties were believed to threaten national parties was by developing into national players in their own right. However, this fear has not come to pass, as even the most prominent regional parties have had difficulty parlaying their regional standings into national success. For instance, in the 2009 general election, Mayawati’s Bahujan Samaj Party fielded candidates in 500 of 543 constituencies across India (incidentally, that is more than any other party). Yet, the party took home only 21 seats—all in its bastion of Uttar Pradesh. In fact, the Bahujan Samaj Party was not even a contender in the vast majority of constituencies in which it entered the fray; its candidates finished among the top two in 72 constituencies in all. Contrast this with the Congress, which contested 440 seats, won 206, and was a top-two finisher in 350 seats around the country. The BJP bagged 116 seats and finished second in another 110 constituencies.

Myth: Regional Parties Rule the Regions

Focusing on national-level statistics is perhaps unfair since India’s states are the areas most likely to come under the sway of regional political parties. After all, it seems intuitive that regional parties would focus on ruling India’s regions. Yet here too, regional parties are far from dominant.

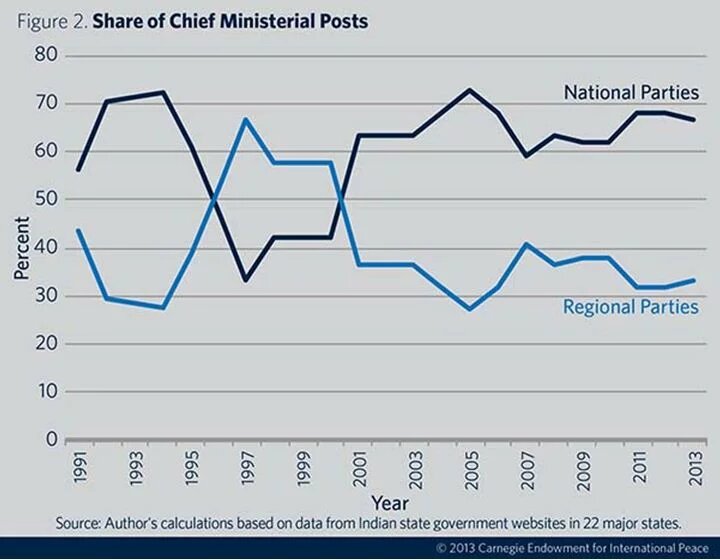

Currently, chief ministers from the Congress or the BJP call the shots in two-thirds of the largest states—fourteen of 22 to be exact—while regional parties control one-third. In the late 1990s, the numbers were completely reversed. Regional parties’ control over states peaked in 1997 and has been on the downswing ever since.

Granted, regional parties do currently rule several key, extremely large states, such as Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, and West Bengal (which together are home to nearly 400 million Indians). But national parties still come out ahead—a majority of Indians today live in states controlled by the Congress or the BJP.

Myth: Regional Parties Are Transforming Governance

Numbers aside, some observers view regional parties as catalysts for redefining governance. To make their case, they point to the rise of a new class of state leaders, like Nitish Kumar of Janata Dal (United) in the state of Bihar or Biju Janata Dal’s Naveen Patnaik of Odisha, who have demonstrated that good economics can also make for good politics. The economist Ruchir Sharma has written that “as a rising force, the regional parties represent hope: they are young, energetic, focused on economic development, and . . . in sync with the practical aspirations of the youthful majority.”

Regional parties have broken the stranglehold of the national parties and, in so doing, have helped usher in a semblance of competitive federalism. Yet regional parties are not unique in offering “hope.” Although there are several notable, long-serving state leaders from regional formations, a number of chief ministers from national parties have also apparently connected with voters in ways that have arguably been both good for governance and electorally rewarding. For instance, two long-serving BJP chief ministers—Raman Singh of Chhattisgarh (in office for nine years) and Shivraj Singh Chouhan of Madhya Pradesh (seven years)—are tipped to win reelection once again this December. Voters have repeatedly rewarded both national party leaders for engineering economic turnarounds in two chronically poor states.

And of course, for every reformist regional party chief minister like Nitish Kumar, under whose reign Bihar’s motto shifted from “jungle raj” to “development (vikas) raj,” there is an Akhilesh Yadav or a Mamata Banerjee. Those two regional heavyweights swept to power with immense goodwill but have fumbled their historic mandates.

In 2012, Yadav, when he was just thirty-eight years old, brought his Samajwadi Party (SP) to power in Uttar Pradesh with a single-party majority—an impressive feat in a diverse state of 200 million. The SP’s last stint in power (2003 to 2007) was marked by brazen corruption and a breakdown in law and order, resulting in the party’s unceremonious drubbing in state polls in 2007. Voters had high hopes that Akhilesh would spurn the ways of his party elders, thanks to his supposedly modern outlook, Western education, and generational bona fides. To date, however, Yadav has failed to offer inspirational governance. To the contrary, with the recent riots between Hindus and Muslims in the Muzaffarnagar District of Uttar Pradesh as a case in point, many observers of the state’s politics believe it is hurtling backward in time.

Banerjee, a former Congress politician who abandoned the party to create her own regional outfit in West Bengal, was also hailed for the change (pariborton) she promised to deliver when elected in 2011. Voters hoped that the fiery leader could overhaul a state that had been badly battered after three decades of Communist rule. But communal clashes and political score settling have badly marred her first three years in office.

While not all of the news has been negative—under Banerjee, for instance, West Bengal has become one of the best-performing states when it comes to cleaning up the power sector by raising chronically underpriced electricity rates—even these good news stories have often been overshadowed by her mercurial governing style. Banerjee famously dismissed a man with the gall to question her economic policies at a public meeting as a “Maoist”; arrested a university professor for penning an unflattering cartoon of her; and publicly accused a rape victim of being a part of a Communist conspiracy to overthrow her.

But what is even more troubling is the limited institutionalization of most regional parties, which calls into question their ability to transform governance. Few have invested in building lasting party structures, instead relying on the charisma of an all-powerful party boss. When election time comes around, many regional parties vest sole control over choosing their slate of candidates with the party leader—hardly bothering with even the facade of intra-party democracy.

The Congress and the BJP are far from paragons of institutionalized party democracy, but for regional parties the situation is more precarious because there is rarely a second-tier leadership beyond the party president. When asked in 2010 about his support for Janata Dal (United) in the coming state elections, an exasperated voter in Bihar explained to me, “My vote is for Nitish Kumar. Besides Nitish, what is [Janata Dal (United)]? . . . If I woke up tomorrow and there were no Nitish—there would be no [Janata Dal (United)].”

Myth: The Influence of Regional Parties on Foreign Policy Is Growing

Beyond India’s domestic political fray, regional parties are sometimes said to have a growing influence over foreign policy. Few can dispute that the role of regional parties as foreign policy actors has grown over time, but it is less clear that recent headline-grabbing tussles signify a new or more significant twist in the struggle for a voice in this arena.

In the past two years there have been two prominent instances of regional parties (and onetime allies of the United Progressive Alliance, India’s governing coalition) inserting themselves into important foreign policy decisions of the central government. Banerjee personally scuttled a water-sharing agreement that New Delhi had painstakingly negotiated with Bangladesh over the Teesta River. The treaty had been a critical component of the central government’s plans to improve relations with its neighbor to the east—that is, until Banerjee effectively vetoed the move. And the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam Party of Tamil Nadu quit the ruling coalition over the center’s support for what the party considered to be a weakly worded UN resolution on the Sri Lankan government’s treatment of its Tamil minority.

Yet, this kind of foreign policy maneuvering is not as new as is often advertised. Since the opening up of the Indian economy in 1991, states have consistently exercised their newfound economic policy latitude to craft their own strategies to woo foreign investors irrespective of New Delhi’s outlook. And on pure foreign policy matters, India’s relations with its neighbors—whether it be Pakistan to the west, Sri Lanka to the south, or Bangladesh to the east—have for many years been colored by the respective positions of the ruling elites in the border states of Punjab, Kashmir, Tamil Nadu, and West Bengal.

Furthermore, the recent embarrassments inflicted on the central government by regional parties over foreign policy may have more to do with the present government’s inept coalition management than the marking of a new era in foreign policy making.

Center-state politics aside, there are limits to states’ activism. Regional leaders may be able to wield (or threaten) veto power, but carrying out an alternative foreign policy requires consent from New Delhi. Even today, state ministers require explicit approval from the central government for both official and private visits they wish to make abroad.

A New Chapter

The emergence of regional parties as major centers of power in India’s politics, economics, and society is one of the most important developments in the country’s postindependence history. And come the general election in 2014, regional parties will play a pivotal role in helping to influence the formation of the next union government. It is even possible that India’s next general elections will produce a “third front” government headed by the leader of a regional party.

Yet, the regional revolution in contemporary Indian politics should not be overstated. India’s regional parties have indeed already risen; whether they can rise further is unclear.

The author thanks Frederic Grare, Devesh Kapur, Arvind Subramanian, and Ashley Tellis for comments. Danielle Smogard provided excellent research assistance.

(This article was first published by Carnegie Endowment for International Peace)