A decade of the 50,000MW Initiative

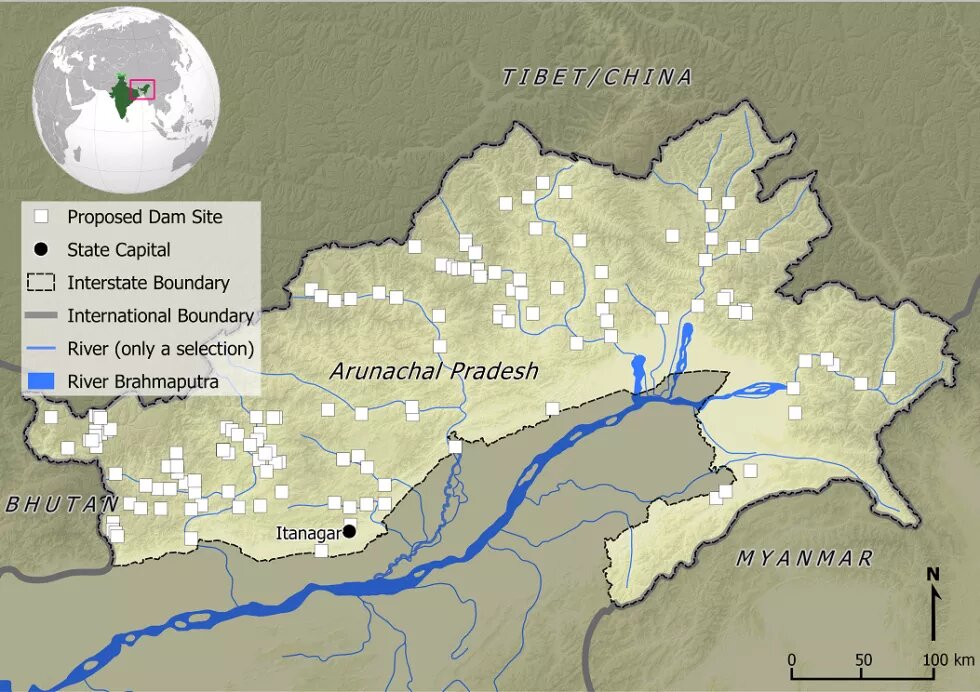

In May 2003, Prime Minister Vajpayee had launched the 50,000MW Initiative, an ambitious programme designed to add 50,000MW of installed capacity of hydropower across sixteen states in the country by the end of the 12th Five Year Plan, i.e. by 2017. The centrepiece of this scheme was to be the state of Arunachal Pradesh in the north east of the country. In the list of 162 hydropower sites identified for the 50,000MW Initiative, 42 projects in Arunachal Pradesh accounted for more than half of the installed capacity. A couple of years later, the Government of Arunachal Pradesh started handing out concessions through Memoranda of Agreement (MoA) to developers, almost all of which were Indian companies; most were medium-sized infrastructure companies from the state of Andhra Pradesh trying their hand at hydropower projects for the first time. By 2009, large-scale projects on almost all the major rivers had been handed out for Survey and Investigation (S&I), the first step towards getting the formal clearances for construction. By 2010, the number of concessions granted exploded to about 150, most of which were projects self-identified by the private companies.

Halfway into the 12th Five Year Plan period, it seems highly unlikely that even one of these projects will succeed in producing a single unit of power by the end of it. Even projects such as the 2000MW Lower Subansiri and the 3000MW DibangMultipurpose projects, which had had a headstartfor S&I and preparation of their Detailed Project Reports, havenot taken off. The Dibang Multipurpose, one of the most visible projects in the national and international media, could not get the necessary environmental clearance to start construction as the public hearing process was thwarted due to local resistance at least ten times over six years. The Lower Subansiri project has been held up at the final stage of installation of the turbines. Among the rest, more than 80 per centare still stuck at the S&I phase. When asked to explain the delay by the state government, the project proponents have averred that S&I work was slowed down by local contestations.

Resistance against Hydropower Development

At first sight, these local contestations appear to begrassroots resistance against potential displacement and impoverishment wrought by development, a phenomenon which defined the debate on development in the 20th century. After all, Arunachal Pradesh is populated by small tribal communitiesand large dams in the past have been disruptive for such communities in India as well as other parts of the world. A closer examination of the Arunachali case, however, indicates that the contestations are more layeredthan merely a “resistance against destructive development”. There is a range of local conflicts being played out: conflict between communities and the state, between communities and private companies, as well as intra-community contestations. These conflicts demonstrate the complexity of the local politics of hydropower development. This complexity is grounded in three main contextual factors:1. The de facto ownership of almost all bio-physical resources by communities; 2. A desire for development and changing livelihoods, and 3.Policy changes for land acquisition.

Arunachal Pradesh is set apart from other better-known cases of hydropower development in the country such as Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand, in that every stretch of hillside and valley, river and stream, is under possession of a tribe, clan or family. Outside of the urban settlements the state government has no cadastral records, let alone any claims of ownership, of land or water. Given this fact, from the point of view of the communities affected by hydropower projects, the state government has no authority to take decisions regarding their lands, and the transaction between the government and the companies has been effectively illegitimate. This became an early trigger for resentment against the state government. The resentment was compounded by the stealth and secrecy that surrounded the process of granting MoA in the first couple of years. There was so little transparency that even the Members of Legislative Assembly of the concerned areas, the highest political representatives, claimed that they too were not informed, let alone consulted.

Under these circumstances, the trust deficit bred in a climate of rumours and misinformation led people to suspect actors within the government of trading off their community lands for private gain. Activists of the Dibang Valley resistance said that they felt that their family heirloom had been pawned by the state government for its own benefit. The lack of information on the ground led to a more severe roadblock for the S&I process: when the hydropower companies moved into the remoter reaches of the state to initiate various S&I activities such as geological drilling and drifting, sediment load measurements etc., they found themselves facing community members who interpreted, and rightfully so, their activities as trespass of ‘private’ property. Without mediation from the government, these frictions frequently led to delay in completion of S&I.

However, in spite of the perceived lack of legitimacy of the government’s decisions and the frictions over trespass, the communities do not necessarily reject the projects entirely. A frequently heard refrain from community gatekeepers is “We are the owners of the land, not the government. The company should have come and spoken to us”.This is because the presence of hydropower companies has created small opportunities for employment and petty contracting during S&I. For many, particularly the smaller groups in the remote swathes of the state, these opportunities are invaluable because currently they are finding themselves struggling in a monetised economy - unable to secure government jobs and failing to make viable livelihoods out of traditional agriculture for supporting modern basic needs of healthcare and education for their children. In such cases, community elites have forged formal organisations which have negotiated agreements with companies on channelling the economic opportunities exclusively to the local stakeholders. Besides jobs and contracts, they also expect private companies to fill in the shoes of the missing state and providesocial infrastructure such as healthcare, education, and roads. Successful negotiations have led to an end of agitations, for example in the case of the 1750MW Lower Demwe project in Lohit district.

Against the economic reality of the region, the Arunachal Pradesh Rehabilitation and Resettlement (R&R) Policy of 2008 is gaining significance. The state R&R policy seeks to redress the dispossession of land and other resources, and displacement through either land-for-land or monetary compensation (whether it can adequately do so is still up for debate). What is more, the state government demonstrated the willingness, at least till 2011, to alter the policy in response to community concerns over compensation rates. For those who have little access to cash income, the possibility of compensating money in exchange for land that they consider unproductive, is a fortunate windfall. At the same time, their calculated participation is tempered with concerns regarding cash being a non-renewable resource that will run out eventually. Individuals have also expressed apprehensions about their ability to invest the windfall in order to gain sustained incomes from it, or their lack of employability at a hi-tech power plant.

As the flow of benefits tends to be towards those with claims of land-ownership, ancient disagreements over land have erupted into legal cases. Family or clan groups within the community have been known to use low-key conflicts as a means of withholding the social license to operate, and thus leverage their own interests into a more favourable position. This also contributed in no small degree to disruptions of field activities for S&I.

Continuing Concerns

These nuances of local contestations against hydropower projects disrupt a simple narrative of ‘simple tribal communities resisting against the environmental monstrosities that are large dams’. Facilitated by policy shifts in terms of recognition of indigenous rights, as well as the land compensation policies, local communities are today in a position to bargain for better livelihoods out of large infrastructure projects. Their conditional consent however does not mean that hydropower development in the region is unproblematic. The opening up of opportunities for livelihoods has in turn generated intra-community conflicts over their distribution. Further, there are limits to the acceptability of hydropower projects at the local level itself. For instance, the likely financial rewards from the hydropower development are much less attractive in the lower valleys where wet rice farming and commercial crops like fruits and spices have been successfully adopted, as in the case of the 2700MW Lower Siang project. In these productive pockets, many community members find the monetary compensation a poor exchange for their fertile valley lands, neither is everybody swayed by the employment opportunities offered by hydropower projects.

Environmental groups who are tracking the process in Arunachal Pradesh have accused the government and project proponents of treating environmental governance measures as a box-ticking exercise, and of taking shortcuts to expedite the clearance process. Then there is the matter of the exclusion of downstream communities living beyond a ten-kilometre radius from the project to count as project stakeholders. This is made possible with an arbitrary10-kilometre radius cut-off point chosen by the central Ministry of Environment and Forests for defining project affected people. This flies in the face of riverine hydrology – the consequences of flow regime alteration do not miraculously stop at ten kilometres. Not only that, the downstream concerns regarding risks and hazards due to seismicity, failure etc. also tend to be ignored. The struggle of the Assamese to be recognised as stakeholders has also led to the prolonged and costly stalemate over the Lower Subansiri Project.

In conclusion, new facets of resource politics are emerging in the case of the hydropower development programme. Local communities desire recognition of their resource sovereignty and want to push the discussion beyond compensation towards sustainable benefit and risk sharing. Unless the backers of India’s hydropower programme at the Central as well as state levels acknowledge and respect this wish, the programme will continue to run aground at every step.