Quantitative goals and a global agreement on zoonosis must be part of the post-2020 biodiversity framework

The International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS) has systematically divided and named all of Earth's 4.5-billion-year history. The length of time has been split from the longest to shortest as eons, eras, periods and ages. According to IUGS, we are currently in the Phanerozoic eon, Cenozoic era, Quaternary period, Holocene epoch, and the Meghalayan age. But many scientists are converging around the understanding that the IUGS classification needs a quick revision. They believe that our planet has already moved into a new epoch called the Anthropocene – the age of humans.[i] This is because humans today have the most dominant influence on the environment and the climate. We are literally changing the face of the Earth. And one of the ways we are doing this is by decimating other species.

We are in the midst of one of the greatest mass extinctions in the history of our living planet. Many scientists have termed this as biological annihilation and sixth mass extinction.[ii] Presently, species are becoming extinct at least tens to hundreds of times faster than without human influence. Only five times before in our planet's history have so many species been lost so quickly. The fifth was when the dinosaurs were wiped out.

Václav Smil, the Czech-Canadian scientist, has brilliantly demonstrated our impact on the biosphere through the weight of all vertebrates on land (mammals, birds, and reptiles put together). According to his calculations, presently, humans and domesticated animals weigh 99 per cent of all vertebrates; the wild vertebrates are just one per cent. Around 10,000 years ago, when humans had just started settled agriculture, the situation was just the opposite – wild vertebrates weighed 99 per cent and humans and domesticated animals only 1 per cent.[iii] Another study has pointed out that for the first time ever in the history of mankind, the global human-made mass – cement and bricks to make buildings, asphalt, and tar for our roads, clothes, metals and plastics and so on – exceeds the weight of all living biomass on Earth.[iv] This trend will have to be reversed if we want to live on a healthy planet. We have an excellent opportunity to reverse the trend by adopting an ambitious post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework. But can the world come together and adopt a meaningful agreement? What are the critical components of an ambitious post-2020 framework? The article attempts to answer these questions.

Biodiversity loss

The future of biodiversity is truly bleak on the planet. A major report published by the Intergovernmental Science – Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) in 2019 found that an average of 25 per cent of all animal and plant species assessed faced extinction, many within decades. This translates into around 1 million species that face extinction unless urgent and drastic action is taken to protect them.[v]

The first-ever report on the Status of Migratory Species, presented to the 13th meeting of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species (CMS COP13), in Gandhinagar, Gujarat in February 2020 showed that the populations of most migratory species were declining.[vi] Another report published in 2020 – World Wildlife Fund’s Living Planet Report – shows an average 68 per cent decrease in population sizes of mammals, birds, amphibians, reptiles and fish between 1970 and 2016.[vii]

In India, while the national animal, tiger, and national bird, peacock, are doing well, a total of 683 of our animal species are in critically endangered, endangered, and vulnerable categories of the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN) Red List.[viii] The State of India's Birds Report 2020, released at CMS COP13, also found that over a hundred species of birds faced the threat of extinction.[ix] Clearly, national efforts to protect biodiversity have proved to be inadequate.

But India and the rest of the world have an excellent opportunity to do something meaningful to not just reverse biodiversity loss but also improve it. Following a series of meetings starting with CMS COP13, the UN Biodiversity Conference was meant to be held in October 2020 to adopt a new global biodiversity strategy for the next decade – the post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework – and decide a longer 2050 goal called “Living in harmony with nature.” The conference has been pushed to 2021, but negotiations on the post-2020 framework are currently ongoing. A zero draft of this framework has been developed, and as the working groups and agencies deliberate on it further, the most important thing would be to get countries to agree to much more ambitious and measurable biodiversity goals and targets than they have done in the past.

Aichi targets

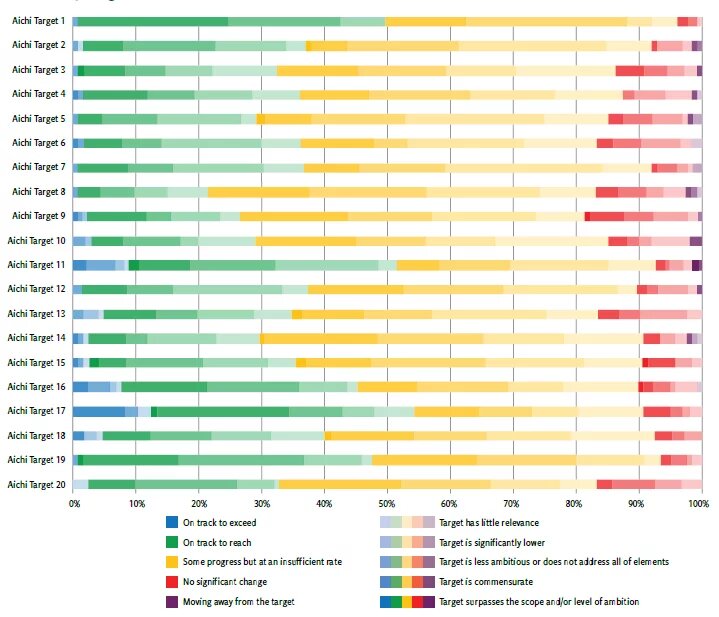

Historically, biodiversity targets have been entirely subjective. For instance, the 2010-2020 goals called the Aichi targets were mostly about legislation, plans, and strategies. During this decade, undoubtedly, there has been a substantial increase in the information on biodiversity available to citizens, researchers, and policymakers. But the Aichi targets have not delivered results. The fifth edition of the Global Biodiversity Outlook was published in 2020 – the final report card on progress against the Aichi biodiversity targets by parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). The report stated that none of the 20 targets had been fully achieved at the global level.[x]

While countries have made efforts to develop Biodiversity strategies and action plans (Target 17), they have done quite poorly in mobilising resources (Target 20). Overall, governments will need to significantly scale up national ambitions and ensure that all necessary resources are mobilised and the enabling environment is strengthened for biodiversity protection.

Figure 1: Global Progress towards Aichi targets

India’s progress

India’s progress against Aichi targets can be termed as ‘satisfactory’. India adopted 12 national biodiversity targets from the 2010 Aichi targets. However, many of these targets are subjective and difficult to measure.

In its Sixth National Report submitted to the CBD in December 2018, India reported being on track to achieve 10 of the 12 targets and making insufficient progress towards achieving the other two targets. These include: i) identifying invasive alien species and pathways, and developing strategies to manage the populations of prioritised species; and, ii) identifying opportunities to increase the availability of financial, human and technical resources to facilitate effective implementation of the Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011-2020 and the national targets.[xi]

Infobox: India’s progress against National Biodiversity Targets

(Source: Sixth National Report submitted by India to the CBD)

Future international cooperation

If international action on biodiversity has to succeed, then it must address four key issues:

- Quantifiable targets;

- Collaboration on research and technology;

- Financial resources; and

- Zoonosis.

(i). Quantifiable targets

The Aichi targets have attracted much criticism for not setting quantifiable goals and measurable targets, and rightly so. There is a famous saying – you treasure what you measure. Given the vast repository of data and information now available on biodiversity, setting quantifiable goals and actionable targets will have to be the way ahead. Such an approach is already commonplace in international conventions and agreements. Take the UN climate change agreements, for instance. Under the Paris Agreement, countries have agreed to keep global warming to less than 2°C, preferably 1.5°C. To meet this goal, countries have submitted their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC), which are also measurable. Similarly, we have the Sustainable Development Goals, also called Agenda 2030, which are accompanied by 169 specific targets and 232 measurable indicators.[xii]

The zero draft has taken note of this criticism, and most of its 2030 goals are intended to be measurable, though the exact targets are yet to be agreed upon by parties. It has also set out a list of four goals for 2050, of which there is one measurable goal:

- The area, connectivity and integrity of natural ecosystems increased by at least [X%] supporting healthy and resilient populations of all species while reducing the number of species that are threatened by [X%] and maintaining genetic diversity;

- Nature’s contributions to people have been valued, maintained or enhanced through conservation and sustainable use supporting global development agenda for the benefit of all people;

- The benefits, from the utilisation of genetic resources are shared fairly and equitably;

- Means of implementation are available to achieve all goals and targets in the framework.

These goals are important, but the question is whether they are ambitious enough, given the crossroads humanity finds itself in today. Going ahead, countries should agree on the post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework that is measurable and mainstreams biodiversity into policies across the whole of government and among all economic sectors.

(ii). Research and technology collaboration

A major critique of the CBD and the corresponding Nagoya Protocol is that they have made collaborative research difficult and, in some cases, impossible by providing countries sovereignty over their genetic resources.[xiii] Others have argued that Article 15 and 16 of the CBD provide a facilitative access regulation framework for genetic resources among member states and enable access to and transfer of technology (including biotechnology) to developing countries under fair and favourable terms.[xiv] However, the truth is that such collaborations are not happening to the extent they should and require further streamlining. Take the case of invasive species.

The IPBES assessment identifies invasive alien species as one of the five major drivers of the current biodiversity crisis. While the prioritisation of invasive species is a work in progress, in many countries, including India, Lantana Camara is arguably a species of high concern. Its invasion threatens more than 300,000 square kilometres of India’s forests, including 40 per cent of its tiger range and is leading to a scarcity of native species for wild herbivores.[xv] Site-specific experiments by forest departments to eradicate the species have failed. Not just India, but other parts of Asia, Africa and Oceania have been impacted by its invasion too. As climate change impacts worsen and extreme weather events become more frequent, the spread of invasive species will happen at a much faster pace.[xvi] International collaboration, in terms of research and technology to manage a species such as lantana, will be crucial to contain the spread.

(iii). Financial resources

Many developing countries like India are struggling with their resource mobilisation. The Indian government’s expenditure on biodiversity conservation efforts has been increased by 82 per cent from 2012-13 to 2016-17.[xvii] This is impressive, but not enough. The annual requirement for biodiversity projects is estimated to be nearly Rs.109,000 crore (US$ 15.6 billion), but the annual expenditure has averaged Rs.70,000 crore (US$ 10 billion), directly or indirectly, through several development schemes of the central and state governments.[xviii] The shortfall is almost 35 per cent and directly impacts implementation. The zero draft of the post 2020 framework tries to address this problem by requiring an “increase by [X%] financial resources from all international and domestic sources”, but international financial commitments have been hard to obtain. At CBD CoPs, developing countries like India and China have been negotiating for financial resource flow targets from developed countries to be defined, but that has not happened.[xix] The UN Biodiversity Conference must address this critical issue.

(iv). Zoonosis

The link between biodiversity and zoonotic outbreaks is becoming clear. The far-reaching and devastating impact of the COVID-19 pandemic is an important reminder to significantly raise the bar in our biodiversity conservation efforts. According to the World Health Organisation, nearly 75 per cent of new or emerging infectious diseases are zoonotic in origin i.e., infectious diseases caused by bacteria and viruses that jump from animals to humans.[xx] The frequency of zoonotic outbreaks has increased in the last 20 years, and the upward trend is likely to continue. Ecosystem degradation and biodiversity loss are among the major causes of such outbreaks.[xxi] As wild animals and humans are now nearby, the spillover of animal diseases into humans is increasing. Ebola, West Nile virus, Nipah and Zika come under this category. Similarly, livestock is also coming in contact with wildlife and transmitting pathogens to people, like the Rift Valley virus.[xxii]

In its implementation support mechanism, the post-2020 framework's zero draft calls for "safety and security in use of biodiversity to prevent spillover of zoonotic diseases, the spread of invasive alien species and illegal trade in wildlife." This cursory mention of zoonoses in the framework will not do much to support international research and collaboration on the subject. A universal code of conduct to address the underlying causes of zoonoses, including biodiversity loss, is the need of the hour. The post-2020 framework must include it as one of its goals.

The last two years have underscored the importance of biodiversity. It has reminded the world, what the destruction of nature and biodiversity can entail for humanity's health and progress. As we emerge from the COVID-19 crisis, we must remember that there cannot be healthy lives without a healthy planet. Therefore, we must come together at the next UN Biodiversity Conference to start a process that builds a better, greener, and sustainable future for all Earth's inhabitants.

ENDNOTES

[i] Colin N Waters et al. (2016). The Anthropocene is functionally and stratigraphically distinct from the Holocene. Science, Vol. 351, Issue 6269, aad2622

[ii] G. Ceballos et al. (2020). Vertebrates on the brink as indicators of biological annihilation and the sixth mass extinction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. Available at: https://www.pnas.org/content/117/24/13596

[iii] V. Cicil. (2019). Growth: From microorganisms to megacities. The MIT Press.

[iv] E. Elhacham et al. (2020). Global human-made mass exceeds all living biomass. Nature Vol 588

[v] E.S. Brondizio et al. (2019). Global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science - Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. IPBES secretariat, Bonn

[vi] UNEP/ CMS. (2020). CMS to Present Preliminary Review of the Conservation Status of Migratory Species. UNEP Secretariat. Available at: https://www.cms.int/sites/default/files/CMS%20COP%2013%20Conservation%2…

[vii] R.E. Almond et al. (2020). Living Planet Report 2020 - Bending the curve of biodiversity loss. WWF, Gland

Available at: https://www.wwf.org.uk/sites/default/files/2020-09/LPR20_Full_report.pdf

[viii] J. Nandi. (2018). Number of Indian species in endangered list going up. Hindustan Times.

[ix] SoIB 2020. State of India’s Birds, 2020: Range, trends and conservation status. The Soil Partnership.

[x] Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity. (2020). Global Biodiversity Outlook 5. Montreal.

[xi] Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change. (2018). Sixth National Report for the Convention on Biological Diversity. Government of India

[xiii] K.D. Prathapan. (2018). When the cure kills – CBD limits biodiversity research. Science Vol. 360, Issue 6396, pp. 1405-1406

[xiv] A. Jojan. (2018). Critiquing Narrow Critiques of Convention on Biological Diversity. Economic and Political Weekly Vol lII no 16 44

[xv] N.A. Mungi et al. (2020). Expanding niche and degrading forests: Key to the successful global invasion of Lantana Camara (sensulato). Global Ecology and Conservation Vol 23

[xvi] IUCN. (2019). A post-2020 target on invasive alien species (IAS).

[xvii] Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change. (2018). Sixth National Report for the Convention on Biological Diversity. Government of India

[xviii] Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change. (2018). India submits Sixth National Report to the Convention of Biological Diversity (CBD). Government of India

[xix] L. Jishnu. (2015). Reluctant funding, Down to Earth

[xx] World Health Organisation and the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity. (2020). Biodiversity & Infectious Diseases: Questions & Answers.

[xxi] Ibid.

[xxii] C. Bhushan. (2020). Zoonotic diseases are rife this century: Globalised world requires global code of conduct to overcome this threat. The Times of India