Access to people’s health data holds the power to influence the governance of their bodies and lives.

Bodies as Data

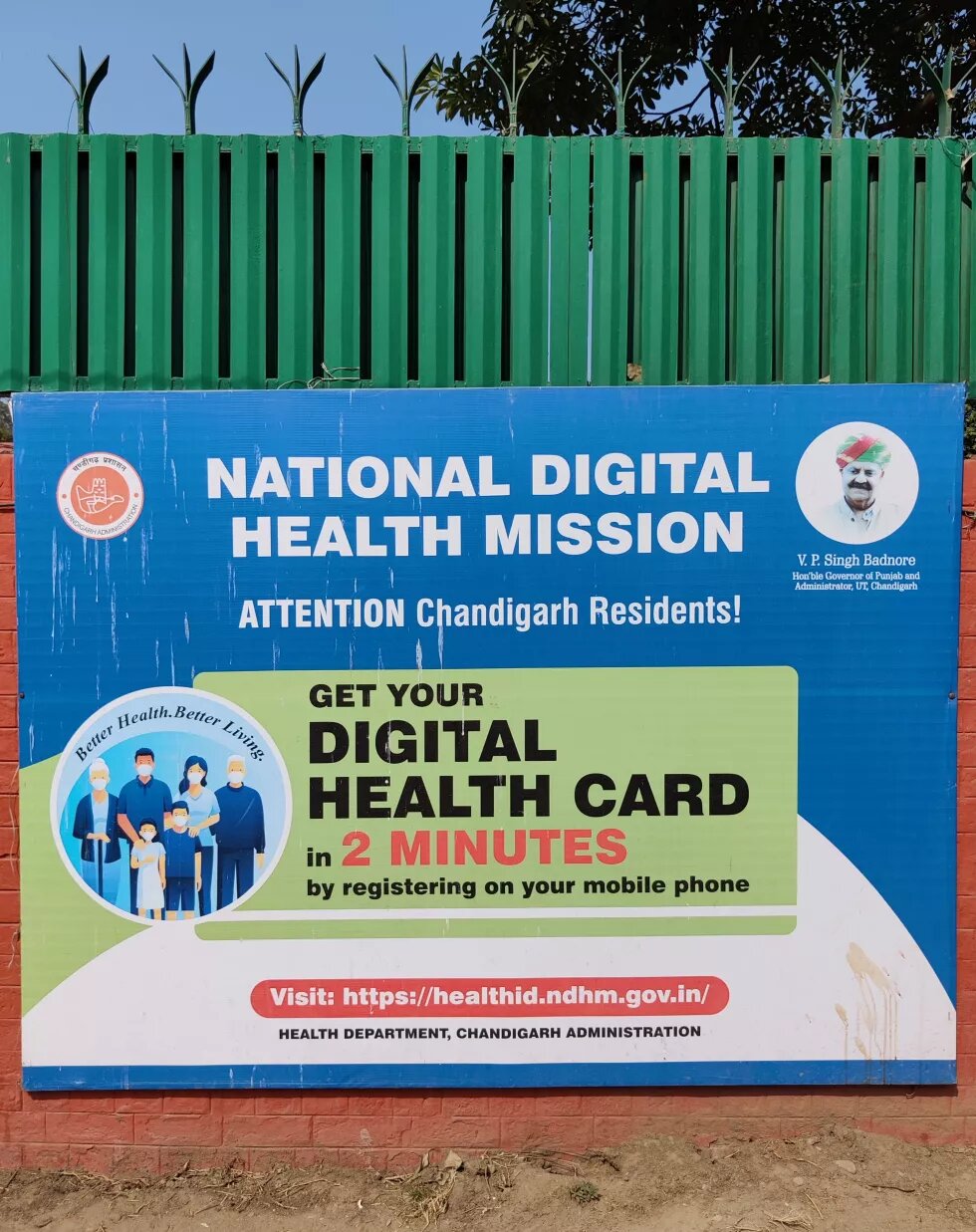

In a small semi-rural civic dispensary on the outskirts of Chandigarh—the capital of the northern Indian states of Punjab and Haryana—I sit across the table from a medical intern in charge of overseeing patient enrollments for the recently launched National Digital Health Mission (NDHM). This union territory is among the seven where the NDHM has been piloted by the Government of India since its launch on 15 August 2020 by Prime Minister Narendra Modi. The NDHM aims to create a national digital health ecosystem, which will provide citizens of India with a unique Health ID to share personal health data among various stakeholders.

According to the NDHM’s health data policy, participation in the digital ecosystem is voluntary, but the medical intern across the table has a different side of the story to share:

“We write on the side of the prescription ‘health ID’ and...we tell our staff that till I don't sign this [saying] that they [patients] have made a health ID... you don't give the medication... It's mandatory because they [NDHM] ask us specifically how many [Health IDs] we make in a day... So they give us targets that this is how much you should achieve in a day. So that's why we have to... force patients to make it.”

The Health ID has also been integrated into the government’s CoWIN (Covid Vaccine Intelligence Network) vaccinator portal and there are many reported instances of Health IDs being registered for people without their consent through this portal at the time of vaccination.

The health workers in Chandigarh showed me a WhatsApp message they received from the health department mentioning that “The registration for generating Health IDs is mandatory for all the citizens of our country.”

Beyond this, health workers have received no information about the NDHM. An auxiliary nurse midwife (ANM)—female health worker based at a primary health centre—complains: “They should tell clearly what this work is for... We don't know absolutely anything.” Consequently, the general public is also unaware of what they are being made to sign up for.

A key principle of the NDHM is that true ownership and control of the personal data will remain with individuals to whom the health data relates. But people cannot meaningfully exercise control over their data if they don’t have any understanding of their participation in the digital health ecosystem.

On a conceptually more fundamental level, ownership is a counterproductive framework for data protection because it is embedded in extractive market logics and ignores concerns of how data shapes societies. Despite this, data ownership is a popular framework because policies view data as a disembodied resource, a capital commodity, property to be owned and traded. Data, after all, is hailed to be the “new oil.”

This dominant framework of data as a resource can be traced back to the field of cybernetics, which conceptualised data as a layer permeating everything while existing independently from the medium carrying it. Till date, this understanding of data as a disembodied resource finds its way into various domains, including the policy frameworks governing the digital health ecosystem in India. These policy frameworks fail to capture the relationships between people’s bodies and their data, and the power relations governing these relationships. This is concerning because disembodiment of data opens it up to possibilities of human exploitation.

Feminists have led the way in foregrounding the relationship between data and bodies by showing that they are intimately interconnected, and calling for a deeper understanding of data as embodied. Feminists argue that data is an extension of our bodies, and control over data is often experienced by people as control over their bodies. For example, victims of non-consensual sharing of intimate images online often describe their experience in terms of physical violence, not in terms of a data protection violation. When viewed through such embodied experiences, we need to rethink data protection policies in a way that has little to do with capitalist relations of exchange and more to do with feminist thinking of the body.

A popular feminist slogan in sex education to teach children about physical boundaries is “my body belongs to me.” There is also a long history of feminists using the slogan “my body is mine” in the fight against sexual violence. These mottos indicate a form of ownership that centres bodily integrity. For instance, when individuals engage in shared sexual experiences, even within market logics such as commercial sex work, the inviolability of the body is still central to that experience. But such concerns of bodily integrity are not covered by the understanding of ownership in our existing policy frameworks, which view health data as a disembodied resource. As a result of this, the intimate relationship between our bodies and health data loses focus, in turn threatening patient rights.

Insuring health data for ensuring wealth

The datafication of health offers potential to improve clinical care. Mr. Arun*, a member of the National Health Mission Employees’ Union, tells me:

“India is right now very backward. In a town like Chandigarh, we don’t have computerised systems. In the future, there is a vision that all doctors will have a laptop, all pharmacists will have a digital record of transactions.”

While such datafication sounds promising, a different side of the story is revealed when bodies are put back into the picture.

Ms. Narima*, an ANM worker at a civic dispensary in Chandigarh, says:

“Everyone in the family won't come [for Health ID registration]. One family member comes with the date of birth of all members and with one family phone.”

When a person is enrolled into the NDHM, their family members are enrolled too, often without their knowledge. This is not only a gross violation of people’s consent and choice, but through this, a person’s health data can also get linked to their family’s health data. This happens through common identifiers like names, phone numbers, addresses, etc., irrespective of whether the family has consented to it, or is even aware of it.

What harm could come from such data interlinkages?

Health data policies have created many provisions and incentives for insurers to be a part of the digital health ecosystem. So patient data within the NDHM ecosystem may be available to private insurance providers in a variety of ways. One way this data sharing could take place is through formal collaborations enabled by the NDHM digital infrastructure.

To illustrate how this would work in practice, consider the case of Kranti, who has a family history of diabetes and gets regular blood-sugar tests done, the results of which she shares with her doctor. Under the NDHM ecosystem, Kranti can add readings from devices like fitness wearables to her digital health records. So her doctor asks Kranti to use a wearable fitness tracker to track her glucose level and automatically share data from the fitness tracker with the doctor.

At the same time, Kranti’s health insurance provider, Max Bupa, has collaborated with GoQii, the company designing Kranti’s fitness tracker. GoQii shares user data from their fitness trackers with Max Bupa, which enables Max Bupa to assign a health score to its policyholders and accordingly offer discounts on insurance premiums. Other health insurers, such as HDFC Ergo, have similar offerings, and the NDHM infrastructure incentivises more takers for it.

When health data is treated as a disembodied resource, it legitimises the sharing of data among more non-clinical stakeholders—such as health insurers—who can derive value for themselves from the resource. But the reason private actors want to access patient data in the first place is because in reality, health data is embodied. In other words, health data says something about the bodies that generate this data, something that private actors have a business interest in knowing and monetising. With all of this interlinked health data available to insurers under the NDHM, they are in a powerful position to access health records of people who have not consented to share this data.

What can insurers do with this data?

Let’s go back to Kranti’s case, whose chances of inheriting diabetes are high though she is actively managing her risk with her doctor. Since health insurance coverage is often offered at the level of families in India, insurers have a business interest in mining data about the health of families. While earlier, insurers would not be able to know about her risk for diabetes unless it is declared by her, they would now be able to access this data at ease. Insurers would now be able to predict if she is likely to get diabetes because of her digital health records, which would be linked to her family’s records in the NDHM ecosystem. This would be possible even without Kranti’s explicit consent, as seen earlier.

As a result of this, insurers can either exclude individuals like Kranti from their insurance policies, or differentially treat them by pricing premiums to account for that risk, based on data obtained through their digital health records as well as the aggregated data of others related to the individual.

This undermines the original purpose of insurance, which is to balance risk in society and protect those most in need. Insurance is predicated on the understanding that everyone deserves medical care without a strain on their finances. But as private insurance providers gather more data about people and are able to make predictions about people’s lives, they can pinpoint the riskiest people and either increase their premiums or deny them coverage, hitting those who can least afford them the highest.

In this way, access to people’s health data becomes a form of power, giving those with such control the unparalleled power to influence the governance of people’s bodies and lives. The disembodiment of data within the NDHM ecosystem creates a scenario where actors controlling its digital infrastructure can now exploit patients from afar, rather than having to control their bodies in person. This happens without patients necessarily knowing what is going on and who has access to information about them.

Aadhaar’s privacy problems

Patients and their families are not only being compulsorily enrolled with Health IDs into the NDHM, they are also being either mandated or nudged towards using Aadhaar—India's 12-digit unique identity numbers for citizens—to do so.

In a rural civic dispensary on the outskirts of Chandigarh, I speak to some data entry operators as well as residents who have come to get themselves enrolled with a Health ID. One can register for a Health ID either through a phone number or Aadhaar, but not only are many people’s phone numbers already linked to Aadhaar, the civic dispensary I’m at is accepting only Aadhaar to register people.

A data entry operator shared that when one registers a Health ID through Aadhaar, the registration form is auto-filled with data linked to their Aadhaar (such as their name, date of birth, photo, phone number). But registration using a phone number needs to be done manually, which makes it more time consuming: “It takes me 15 minutes per registration through phone number, and just 5 minutes through Aadhaar,” says one of them. Another reason why Aadhaar is preferred is that it does not require a password for the registration, but the mobile phone number registration requires one. This is a challenge due to the low digital literacy in India: “Some people find the password difficult to generate… So they prefer to register through Aadhaar.”

In some cases, people are being explicitly required to link their phone numbers with Aadhaar if they choose to enroll for the Health ID using their phone numbers. This happened to Mr. Rizwan*, a caterer in Chandigarh who had visited a civic dispensary to get his Health ID made:

“Mine [my Health ID] did not get made… My mobile number was not linked to [Aadhaar card]... I went and got it linked just now.”

In this way, there are many system-based and structural incentives or ‘nudges’ that have been designed to link a person’s Aadhaar number with their Health ID, and Aadhaar details eventually get linked to a person’s digital health data records.

Why is this a problem?

Aadhaar has been shown to be an exclusionary form of digital biometric identification. When linked to healthcare, it could have dire consequences. Recently in Bangalore, the capital of the Indian state of Karnataka, a COVID-19 patient died after two hospitals denied him treatment without his Aadhaar card details.

Aadhaar is premised upon the datafication of our bodies. When people are denied access to healthcare because they do not have Aadhaar, it shows that without linking our bodies to our biometric data, we cannot 'prove' whose body this really is, even if our bodies are physically present to access healthcare. This is based on the assumption that the data generated from our bodies is the only objective form of identification. Data, in this case, is understood to be merely a resource to be mined to yield ultimate truth.

This has severe consequences, especially for patient privacy, when Aadhaar is linked to health data. In 2015, the National Aids Control Organisation (NACO) began urging states to collect the Aadhaar numbers of people living with HIV (PLHIV) to link them with their patient identity cards issued by antiretroviral therapy centres. Due to the stigma surrounding HIV/ AIDS in India, many PLHIV started dropping out of treatment programmes for fear of being identified through a breach of their privacy.

Remember those insurance companies in Kranti’s case, profiting off her health data? They're present in this case too. One of the fears of PLHIV in 2015 was that databases being formed on the basis of the Aadhaar numbers could be seeded by private actors and be used by health insurance companies to deny them insurance.

What can we learn from this incident?

When states insist on people identifying themselves at the cost of their privacy to receive treatment, those most in need of healthcare are most likely to refuse it. This is bound to repeat with the NDHM because health data would be stored in databases accessible to many actors, including but not limited to health insurance companies, as we saw earlier.

What we can also learn here is that a loss of control over who can access one’s health data blurs the contextual boundaries that structure a patient’s privacy expectations. PLHIV may be comfortable sharing their HIV status with their doctors within the context of clearly defined clinical boundaries, such as patient-doctor confidentiality, which prevent their data from being shared with others. But the involvement of private actors such as insurers enables this patient data to now flow into proprietary databases which patients already facing stigma may not be comfortable with.

This is concerning not only because such legibility challenges one’s ability to live a life free of capital and state control, but also because it fails to account for the boundaries of privacy management within one’s own home. PLHIV don't always share their HIV status with family members. If Health IDs are interlinked as we saw earlier, and consequently known to all family members, PLHIV would lose control over the decision of whom to share this information with and when. This hampers not only their privacy but also their autonomy to make decisions about their own bodies.

In this way, threats to patient rights under the NDHM not only affect data, but have far-reaching social consequences for the bodies and lives of people, with the worst affected being the marginalised with stigmatised health conditions.

Conclusion

We are at a stage in time when the datafication of health is undergoing crucial shifts. The critical perspectives, medical legislation and codes of ethics that have been developed over the years to safeguard patient health data and associated healthcare rights are falling short in this age of big data.

Patients and their families being compulsorily enrolled with Health IDs, implicit or explicit requirements of linking Health IDs to Aadhaar, a larger focus on data collection than on raising awareness about the datafication of health, and threats to patients’ privacy are all major violations of patient rights.

The NDHM’s underlying framework of health data as a resource and source of capital is core to why these rights are undermined. In reality, harms from data violations impact people’s bodies and lives intimately. The violations of these rights come into picture only when we put bodies back into the framework and question not only how data may be harmed, but how bodies may be harmed through their data. Failing to recognise the relationship between health data and bodies undermines patients’ right to healthcare and risks their exclusion and exploitation, hitting those in crucial need of healthcare the hardest.

NOTE:

This essay is based on a research study conducted for the paper:

Radhakrishnan, Radhika. (2021). Health Data as Wealth: Understanding Patient Rights in India within a Digital Ecosystem through a Feminist Approach. Data Governance Network, Mumbai.

(The research was carried out by the author during her employment as a Researcher at the Internet Democracy Project)

All names indicated with an * are changed names as per the request of research participants. All quotes are translated from Hindi.

Disclaimer:

This article was prepared with the support of the Heinrich Böll Stiftung. The views and analysis contained in the publication are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the foundation. Heinrich Böll Stiftung will be excluded from any liability claims against copyright breaches, graphics, photographs/images, sound document and texts used in this publication. The author is solely responsible for the correctness, completeness and for the quality of information provided.