A proof of identification is necessary for all individuals. But asking trangender persons to undergo medical certification as proof of existence violates their right to privacy.

Professor Philip Alston, UN Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights, writes in his October 2019 report to the UN General Assembly[i]:

[T]he digital welfare state is either already a reality or is emerging in many countries across the globe. In these states, systems of social protection and assistance are increasingly driven by digital data and technologies that are used to automate, predict, identify, surveil, detect, target and punish… [A]s humankind moves, perhaps inexorably, towards the digital welfare future it needs to alter course significantly and rapidly to avoid stumbling zombie- like into a digital welfare dystopia.

Transgender persons or those who do not identify with the gender assigned to them at birth, have been targeted, surveilled and punished long before the emergence of the present day “digital welfare state”. The violation of the right to privacy and consequently, the liberty of transgender persons can be traced back to the colonial state viewing them through the lens of surveillance using the Criminal Tribes Act, 1871[ii]. Although these communities were declared ‘denotified’ in 1952[iii], the practice of systemic transgender surveillance continued with laws such as the Telangana Eunuchs Act[iv] and Karnataka Police Act, 1963[v] until recently.

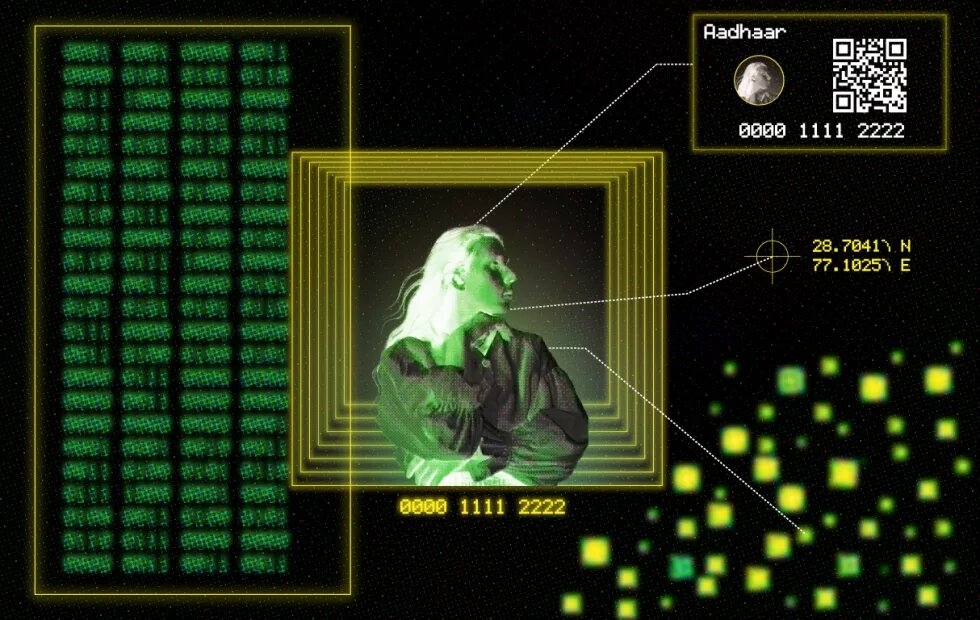

Accessing social welfare for disadvantaged communities including those covered under the socially and educationally backward communities (SECs) requires individuals to have a proof of identity document to verify the specific identity, be it gender for transgender persons (transgender card) or disability (Unique Disability ID) or caste (caste certificate). While a proof of identity is necessary to validate one’s identity to access identity-specific state welfare, all these identity documents have specific certifications required to procure them. Further, these documents either have a digital process to procure them or are to be linked to their Aadhaar, the biometric-based digital ID in India[vi], which then digitally maps their bodies to specific identities. The interdependency of documents becomes a complex maze to manoeuvre for transgender persons, especially for those with multiple marginalisations owing to varying degrees of discrimination faced by them at different touch points.

This essay unpacks the process of changing identification documents for transgender and intersex persons after the enactment of the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act 2019 (henceforth Trans Act), a statute passed to protect the rights of transgender persons. This essay will also look at the need for multiple certifications and identification documents and the body politics involved for transgender persons living with multiple marginalisations and the additional labour expected from these individuals who are from marginalised backgrounds to become a part of the system and thus proving eligibility to access welfare in a digital welfare state. The intent is to highlight the systemic discrimination of certain bodies in order to enter the state’s [digital] data systems that act as entry barriers, thus determining their eligibility to access to their rights, including their right to privacy guaranteed by the Constitution of India.

Labour of multiple (digital) certifications for the marginalised

The Trans Act 2019 prescribes a two-step digital process for changing name and gender on different identification documents under Section 6 and Section 7 of the statute with details for the process under Rules 5-7 of the Trans Act Rules 2020. All individuals who wish to access any state-sanctioned welfare for transgender persons are expected to procure a transgender certificate issued through the National Transgender Portal[vii]. There are several layers of challenges with the document changing process. To begin with, this process is dependent on existing identification documents. Being ostracised by their family, transgender persons often run away from their home to escape the abuse from their natal families and do not have a valid identification document. Owing to the historic marginalisation and invisibilisation, transgender persons have not had the access to a level of education, enough to manoeuvre a digital process to change their gender and name on identification documents. Further, individuals who identify within the binary genders of male and female are expected to submit a medical certificate. Although the Trans Act explicitly deems physical checks as illegal, such arbitrary physical checks continue in several parts of the country. Accessing trans-friendly medical professionals continues to remain a challenge for transgender persons. Only those clued into the community networks have access to the limited list of trans-friendly medical professionals. Besides, the application forms are available only in English or Hindi. This further makes the application process inaccessible for transgender persons in rural parts of states such as Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Tamil Nadu, among others where individuals might not know either of these two languages. Further, the delay in the approval process of the applications continues, especially for the second step with medical certification under Section 7 of the Trans Act. Although other identification documents may be used as proof for this process, individuals are expected to submit their Aadhaar.

The plot further thickens for individuals who experience multiple marginalisation such as being intersex or from the Dalit community or living with a disability. Not all intersex persons identify as being transgender. Although intersex is mentioned under the definition of transgender in the Trans Act, the Act does not have specific provisions to address the violations experienced by intersex persons like the non-consensual surgeries on intersex infants. The Trans Act does not provide an option for intersex persons to identify themselves as intersex. Instead, intersex persons are expected to certify themselves as transgender if they wish to change their name and gender on their identification documents. Caste certificate and Unique Disability ID (UDID) are identification documents that require a copy of other identification documents making it a continued challenge for transgender persons who may be from the Dalit community and/ or living with a disability, thereby further marginalising them. Dalit trans persons continue to face both caste and gender-based discrimination while changing their caste certificate. The application for a UDID includes an additional gender category, ‘Other’. An additional category on the application form is insufficient support for trans persons with disability who need to undergo another medical certification process to also certify their disability. Due to the stigma of being transgender, persons with disability procure a UDID card under the Rights of Persons with Disability Act 2016 using their given name and assigned gender. This card is necessary to access any state-sanctioned benefit for persons with disability. For transgender persons with disability, the name on the UDID card has to match with other identity documents. The process to procure the UDID card is entirely online. The dependency of this process on Aadhaar makes it harder for persons with disabilities to procure a UDID.

“Persons with problems related to dexterity find fingerprint scans tedious since many may not qualify for a medical certificate exempting them from the biometric process. The process is similarly inconvenient for anyone with minor physical disfigurements. Persons with visual impairments who do not qualify for a retina scan exemption might face irritation and discomfort due to photosensitivity or may be unable to focus their eyes on a fixed spot.”

– Soumya Singhal, Aadhaar, Accessibility, and Ableism: Gauging the Responsiveness of Public Services Framework towards PwDs.[viii]

Thus the processes required for transgender persons to change their names and gender on different documents to enter the system in their different identities and the interdependency of documents continues to keep them excluded in a digital welfare state. The need for multiple digital certifications for different marginalised identities adds to the existing complexities further marginalising the most vulnerable. Datafication of individuals using digital processes has been prioritised over accessible processes for those already marginalised. Despite the many challenges and other entry barriers, the onus continues to remain on the individuals to turn themselves into data to be digitised into data systems to be viewed by the state as valid human beings. The inability to do so leads to lack of access to welfare, rights and more importantly, erasure for the most vulnerable in our country.

Play-off between right to life and right to privacy

The Supreme Court of India in its verdict, Puttaswamy Vs. Union of India[ix], recognised the right to privacy as a fundamental right of every individual that is enshrined in the Constitution. However, the Trans Act does not explicitly address individual right to privacy of transgender persons who have a long history of being subject to various kinds of violations and discriminations. On the contrary, as seen above, the Trans Act legitimises the certification of certain bodies over others by the state and the inability to do so could lead to exclusion.

The need for a certificate of identity to access state-sanctioned welfare means that those dependent on the state do not have a choice but to disclose their transgender status while interacting with the state. Although those who are not dependent on the state welfare can excuse themselves from disclosing their transgender status, these individuals still require their changed identification documents to access all other services. Any delays in changing the name and gender on their documents could lead to breach of privacy due to several reasons including name and gender mismatch with their appearance, misgendering, among others. Often, transgender persons create social media accounts in their self-identified name and gender as a way to live in the gender expression of their choice, away from the eyes of their families and friends. The use of social media accounts as logins to access other services, however, could also digitally map the mismatch in their name and gender due to the inability to produce valid identification documents in one's self-identified name and gender. Large volumes of data collected using Aadhaar, social media platforms and other services may be used to profile individuals, making transgender persons appear fraudulent for having multiple accounts without disclosing their transgender status. India recently enacted the Digital Personal Data Protection Act 2023. This new law has been criticised for the extensive power in the hands of the state to access and process the personal data of individuals rather than data protection or the protection of individual right to privacy. This provision of the statute further strengthens the legitimacy of demanding certification and data from transgender persons to be seen as valid human beings by the state. This law also exempts entities determining the purpose or means of processing personal data from the application of certain provisions including the need to give notice for consent to individual users/ customers. Similarly, the caste certificate and UDID are to be linked to an individual's Aadhaar. This further weakens the right to privacy of transgender persons, who have been historically surveilled by the state and with no guarantees of access to their rights. Thus the state’s focus continues to be the collection of data as proof of eligibility for welfare, instead of provision of welfare for those most marginalised.

Conclusion

While a proof of identification is necessary for all individuals, the expectation from a certain group of individuals to undergo medical certification as proof of existence — a process that cisgendered persons aren’t expected to undergo — violates the right to privacy of individuals who are transgender. Besides, the presence within data systems does not guarantee access to welfare. It is only to be seen as making them eligible and part of the system. Persons from marginalised communities are subject to multiple rounds of different certifications that further marginalises them making it harder for them to become a part of the digital welfare state. In the case of transgender persons, the state has legitimised the medical certification process using the Trans Act, which then inherently violates the right to privacy of transgender persons in the name of protection. Thus, the state reiterates the body politics surrounding certain bodies and their hierarchies that existed pre-digitisation using digital gatekeeping to surveil the bodies that enter its data systems in order to determine the kinds of bodies that are eligible for and deserving of human rights and state sanctioned welfare.

I conclude with words of Shivangi Narayan, the author of Surveillance as Governance on the use of data generated from citizens through identification systems, “The government wants to use this data to decide whether citizens as a whole need welfare at all. Not just what it says in Aadhaar promotions – to target welfare better – but over a period of time decide whether welfare in itself is a good strategy… Government also wants to know whether you really are who you claim to be. In other words, are you destitute enough to warrant social security?”[x]

Note: This article is based on the findings of the study, Gendering of Development Data in India: Post-Trans Act 2019 undertaken by Brindaalakshmi K for the Association for Progressive Communications as part of the Our Voices Our Futures project.

Endnotes

[i] Office of the High Commissioner, Human Rights, United Nations. (2019, October 17). World stumbling zombie-like into a digital welfare dystopia, warns UN human rights expert. Retrieved from https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=25156

[iv] https://clpr.org.in/litigation/pil-challenging-the-constitutionality-of-the-telangana-eunuchs-act-1919/

[v] https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/bengaluru/Karnataka-govt-deletes-eunuchs-from-police-records/articleshow/53230231.cms

[vii] National Transgender Portal https://www.transgender.dosje.gov.in/Applicant/Registration/DisplayForm2

[viii] Singhal, Sowmya (2021, July). Aadhaar, Accessibility, and Ableism: Gauging the Responsiveness of Public Services Framework towards PwDs. Social and Political Research Foundation. Retrieved from: https://sprf.in/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/SPRF-2021_Comm_Aadhaar-and-Ableism_Final.pdf

[ix] Justice K.S.Puttaswamy(Retd) vs Union Of India - https://indiankanoon.org/doc/127517806/

[x] Narayan, Shivangi (2021). Surveillance as Governance - Aadhaar | Big Data in Governance. Page 6. Peoples Literature Publication