A well-designed industrial restructuring plan, backed by appropriate fiscal instruments, can usher in change with minimum disruption.

1. Introduction

The global community has limited time to act on climate change mitigation if it wants to avoid the irreversible, catastrophic impacts. Two reports this year have raised the “red alert”. First is Net Zero by 2050: A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector, by the International Energy Agency (IEA), which underscores the scale and urgency of action that must be undertaken to ensure that, in the next three decades, all nations remain on-track to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement of 2015.[i] There is also Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis, Working Group I, Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which warns of the increase in frequency and intensity of extreme weather events that will affect economies and people across the world.[ii]

For India—heavily reliant on fossil fuels for its energy needs and industrial growth, while also being highly vulnerable to climatic impacts—the next three decades will be critical in every aspect. At present, about 70 per cent of India’s primary energy supply relies on two fossil fuels: Coal and oil. Of this, coal has a share of 44 per cent, and oil, 25 per cent (IEA, 2020). Country has now pledged a net-zero target for 2070 at CoP 26 in Glasglow. Two recent modelling studies on India’s net-zero pathways provide a glimpse of possible trajectories to reduce fossil fuels over the next three to four decades.

According to a study by the IEA, India’s coal demand must be halved by 2040, and reduced by 85 per cent by 2050.[iii] Another study, by The Energy Resources Institute (TERI) and Shell, recommends a 60 per cent decline in demand for both coal and oil by 2050.[iv]

Table 1: Net-Zero Pathway by Mid-2060

Table 2: Net-Zero Pathway by 2051

Phasing down the production and use of coal and oil will have a heavy bearing on the sectors that are reliant on them. In addition to a rapid shift from coal-based thermal power to renewable electricity—the energy transition India is already experiencing––re-invention of downstream sectors, especially steel, cement, automobile and fertiliser, will also be necessary. However, the rapid energy transition and industrial transformation required to address the climate crisis cannot be an isolated technological exercise. The nature of the Indian economy, where informal workers account for 90 per cent of the workforce,[v] requires the re-invention of energy and economic pathways to be a socially responsible exercise. It must take into consideration the distribution of the workforce in various sectors, the livelihood dependence of local communities on these sectors, and the socio-economic conditions of fossil fuel dependent areas and their resilience. The question of a “just transition” therefore becomes extremely important.[vi]

2. A sector-wide outlook for just transition

In India, coal dominates the primary energy mix.[1] However, the consideration for a just transition cannot be only coal focused. To achieve the net-zero emission targets through transformative changes, over the next three to four decades, just transition should be planned for all sectors that have competitive alternative technologies with significant emission reduction potential.

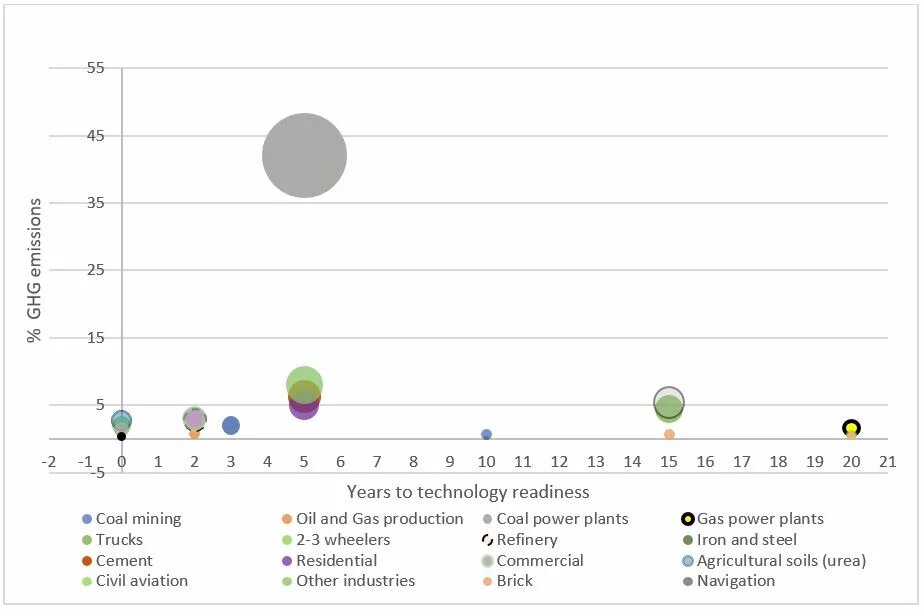

For example, an assessment of greenhouse gas (GHG) emission reduction potential and the availability of alternate technologies suggests that the sectors that need to be prioritised for a just transition include coal mining, thermal power plants, road transportation, other industries, and agriculture soil (urea use). These sectors collectively emit 64 per cent of India’s GHG, and 90 per cent of the technologies required for their transition will be commercially available within the next five years (See Figure 1), making the next 10 years crucial for planning a just transition. In other coal-dependent sectors such as steel and cement, just transition will be viable only in the 2030s. The remaining industries and agriculture soil are likely to see a progressive transition.[vii]

Figure 1: Emissions Versus Technological Readiness

3. Potential impacts and priorities

The transition to clean energy in India will have a huge impact on fossil fuel communities and economies across the country. Three parameters—spatial impact, workforce impact, and revenue impact—provide an understanding of what a clean energy transition will look like and what it will entail.

3.i Spatial impact: Out of the 718 districts in India, 120 have a significant proportion of fossil fuel or fossil fuel dependent industries—coal mining, oil and gas production, thermal power plants, refineries, steel, cement, fertiliser (urea), and automobile. These districts together have a population of approximately 330 million, i.e. 25 per cent of the country’s total population. During the next two to three decades, energy transition will affect all 120 districts to various degrees,[viii] but over the next decade, just transition planning should be prioritised for the 60 that account for 95 per cent of coal and lignite production, 60 per cent of thermal power capacity, and 90 per cent of automobile and automobile component manufacturing. About one-third of these districts are concentrated in the coal belt of Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Odisha and West Bengal (See Figure 2).

Figure 2: Priority Regions for Just Transition in This Decade

To be sure, the states and districts that will face the most imminent challenges of a clean energy transition in this decade are also the ones that remain extremely vulnerable to climate change impacts (See Figure 3).[ix] This is due to the districts’ high proportion of below poverty line population,[x] compounded by the poor state of healthcare, education and living standards.[xi]

Figure 3: Most Vulnerable States to Climate Change

3.ii Workforce impact: A clean energy transition in the coming decades (See Table 3) will impact the approximately 21.5 million people who work in fossil fuel and fossil fueldependent sectors in India. The impact will be worst for the informal workforce, which is nearly four times the formal workforce.[xii] The informality is particularly high in sectors such as coal mining, steel, cement, and fuel retail, and the majority of such workers are low-skilled, have poor education, and earn a low income.

An energy transition will have three primary types of impact on the workforce, which must be addressed through appropriate transition planning.

- Job loss due to declining production and eventually closing down of operations;

- Increased retraining and reskilling requirements for the existing workers due to changes in production processes or repurposing of facilities; and,

- Skilling of the new workforce to meet the requirements of new low-carbon industries.

Table 3: Estimated Workforce (in Million)

3.iii Revenue impact: Fossil fuel transition will have a significant impact on public revenue at the Centre and state levels. Coal, oil, and gas collectively contribute 18.8 per cent of the total revenue receipts of the Central government and about 8.3 per cent of the total revenue receipts of the state governments. Approximately 91 per cent of revenue contribution is from the oil and gas sector; coal contributes only about nine per cent.[xiii] Therefore, from a just transition perspective, oil and gas sector transition will have a far significant impact on public revenue as compared to the coal sector.

The revenue loss from coal mining, however, will affect the state governments, particularly in states where coal mining is concentrated. For states, the main source of coal-based revenue is royalty and contributions from the District Mineral Foundation (DMF). In most top coal states, such as Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh, the share of direct revenue from coal mining (considering the PSUs, which are the major operators) is about five to six per cent of the total state revenue.[xiv] Furthermore, many states and union territories earn a significant amount of revenue through sales taxes of petrol and diesel. Collectively, the sales taxes from petrol and diesel in some of these states, such as Odisha and Madhya Pradesh, are much higher than the coal mining revenue (See Table 4). Consequently, automobile transition due to electrification of vehicles, which is already significant for two-wheelers that consume 60 per cent of petrol,[xv] will cause considerable revenue loss for states.

Table 4: Sales Taxes from Petrol and Diesel, and Direct Revenue from Coal Mining

4. What will just transition entail?

‘Just transition’ in India will necessitate a development intervention to minimise negative impacts of an energy and industrial transition on the fossil fuel dependent states, districts, workers, and the local community. To this end, the following five factors (5Rs) will be crucial:

- Restructuring of the economy and industries;

- Repurposing of the land and infrastructure;

- Reskilling existing and skilling new workforce;

- Revenue substitution and investments in just transition; and,

- Responsible social and environmental practices.

4.i Restructuring of the economy and industries: The fossil fuel districts will require a restructuring of economic and industrial activities to diversify the economy. Currently, most of the coal districts in India are mono-industry districts, which undermine the potential of other sectors. For example, in the Korba district of Chhattisgarh, which accounts for about 20 per cent of India’s coal production, mining contributes to nearly 50 per cent of the district’s GDP. Even in districts such as Ramgarh of Jharkhand, where 50 per cent of the mines are considered unprofitable, coal and coal-based industries contributes over 40 per cent of the district’s GDP.

A well-designed industrial restructuring plan, supported by appropriate fiscal instruments, can facilitate a transition with minimum disruption. This will involve formulating appropriate industrial policies by the concerned state governments as well as district development plans in consultation with local institutions. Furthermore, economic and industrial restructuring should harness the potential of local resources. In many fossil fuel districts, there is substantial scope for boosting the local economy and creating sustainable industries based on agricultural and forest products, aquaculture, dairy, and sustainable tourism. For instance, India’s top coal mining districts have over 31 per cent forest cover on average, which is 10 per cent higher than India’s total average.

4.ii. Repurposing of the land and infrastructure: One of the biggest challenges to developing new industries is the availability of land and its acquisition. This can be addressed by repurposing land and infrastructure from existing fossil fuel industries. An estimated 0.45 million hectares (ha) of land is available with coal mining and major coal allied industries, including coal-based power, iron and steel, and cement. Indeed, coal mines and power plants alone hold about 0.3 million ha of land.[xvi]

Land reclamation also creates both immediate and long-term economic opportunities. In the short term, land reclamation and redevelopment will require the engagement of large numbers of skilled and unskilled workers, creating direct employment. In the long term, well-planned infrastructure projects with complementary investments can have far-reaching benefits for the local economy.[xvii]

4.iii. Reskilling existing and skilling new workforce: To offset the impact of job losses from a fossil fuel transition and to aid the workforce impacted by the restructuring of industries and repurposing of facilities, a progressive skilling plan will be necessary. Sectors that will experience the highest number of job losses include coal mining, coal-based power, automobile ancillary industries and refineries, given their progressive phasing down of operations in the coming decades. Alternative job opportunities must therefore be created for these sectors on priority. In the other sectors, a well-planned reskilling and skilling programme will avoid job losses. Additionally, timely intervention through reskilling and retraining can help informal workers to get readily absorbed in alternative income opportunities.

4.iv. Revenue substitution and investments in just transition: The central government must plan for the substitution of public revenue from fossil fuels, with the state governments playing a role in just transition financing through public revenue. In this context, both DMF funds and GST compensation tax is crucial. The most significant tax on coal is the GST compensation cess (originally instituted as the coal cess to fund green energy transition), levied at Rs.400 per tonne on the dispatch of coal and lignite; in 2019–20, it amounted to an estimated Rs.400 billion. However, this cess will lapse in 2022, providing an opportunity to reverse this to coal cess and use it for just transition in coal-mining areas. Similarly, DMF funds available for place-based investments must be aligned to just transition investments, which currently have a cumulative accrual of about Rs.185 billion in the coal-mining districts.[xviii]

4.v. Responsible social and environmental practices: Just transition must include responsible social and environmental practices, capitalising on the opportunity to reverse the resource curse and form a new environmental and social contract between the people, the government, and the private sector.

Over the years, resource extraction has led to pollution, ecological destruction, and large-scale displacement and deprivation of local communities in India, rendering many fossil fuel (particularly, coal) regions poor and underdeveloped. Moreover, local communities have been alienated and often excluded from decision-making processes. The “new contract” should address these issues—ensuring inclusive decision-making, poverty alleviation, fairer income distribution, and investments in human development and social infrastructure at the social level, and ecological protection and restoration at the environmental level. This will, in turn, enhance sustainable livelihood and income opportunities.

For the next three to four decades, just transition must be planned as a strategic development intervention. Such a transition cannot be executed hastily or abruptly, and a long-term road map must be developed—factoring in the emission reduction targets and the opportunities in hand—to usher in a transformative change that is inclusive, just and viable.

Endnotes

[i]International Energy Agency, Net Zero by 2050: A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector, Paris, France, 2021, https://www.iea.org/events/net-zero-by-2050-a-roadmap-for-the-global-energy-systemInternational.

[ii]Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Sixth Assessment Report, 2021, https://www.ipcc.ch/assessment-report/ar6/.

[iii]Energy Agency,“India Energy Outlook 2021,” IEA, Paris, France, 2021, https://www.iea.org/reports/indiaenergy-outlook-2021.

[iv]TERI and Shell, “India: transforming to a net zero emissions energy system,” Shell, 2021, https://www.shell.in/promos/energy-and-innovation/india-scenario-sketch….

[v]Labour Bureau, Ministry of Labour and Employment, “Employment in Informal Sector and Conditions of Informal Employment,”Vol. IV, 2013–14, Government of India, 2015, https://labour.gov.in/sites/default/files/Report%20vol%204%20final.pdf.

[vi] E. Morena, D. Krause andD. Stevis(eds.),Just Transitions: Social Justice in the Shift Towards a Low-Carbon World (London: Pluto Press, 2019).

[vii] C. Bhushan and S. Banerjee, “Five R’s: A Cross-sectoral landscape of Just Transition in India,”International Forum for Environment, Sustainability and Technology (iFOREST), New Delhi, 2021.

[viii]C. Bhushan and S. Banerjee, “Five R’s: A Cross-sectoral landscape of Just Transition in India.”

[ix]Department of Science and Technology,“Climate Vulnerability Assessment for Adaptation Planning in India Using a Common Framework,” Ministry of Science and Technology, Government of India, https://dst.gov.in/sites/default/files/Full%20Report%20%281%29.pdf.

[x]ibid

[xi]C. Bhushan and S. Banerjee, “Five R’s: A Cross-sectoral landscape of Just Transition in India.”

[xii]Venumuddala, V.R. (2020). NSS data as cited for Informal Labour in India. Indian Institute of Management, Bangalore. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2005.06795.pdf

[xiii]Prayas (Energy Group), “Energy: Taxes and Transition in India,” Working Paper, 2021, https://www.prayaspune.org/peg/publications/item/485-energy-taxes-and-t….

[xiv]C. Bhushan and S. Banerjee, “Five R’s: A Cross-sectoral landscape of Just Transition in India.”

[xv] S. Anup and A. Deo,“Fuel consumption standards for the new two-wheeler fleet in India,” International Council on Clean Transportation, 2021, https://theicct.org/sites/default/files/publications/fuel-consumption-2….

[xvi]C. Bhushan and S. Banerjee, “Five R’s: A Cross-sectoral landscape of Just Transition in India.”

[xvii]Parikh, V., Jijo, M. & Aritua, B. (2018). How can new infrastructure accelerate creation of more and better jobs? World Bank Blogs. https://blogs.worldbank.org/jobs/how-can-new-infrastructure-acceler¬ate-creation-more-and-better-jobs.

[xviii]Ministry of Mines, DMF/PMKKKY dashboard. Government of India, 2021, https://mines.gov.in/writereaddata/UploadFile/DMF_Collection.html.