References of trans masculine identities in Indian traditional and mythological stories, though not as recurrent compared with trans feminine identities, did exist

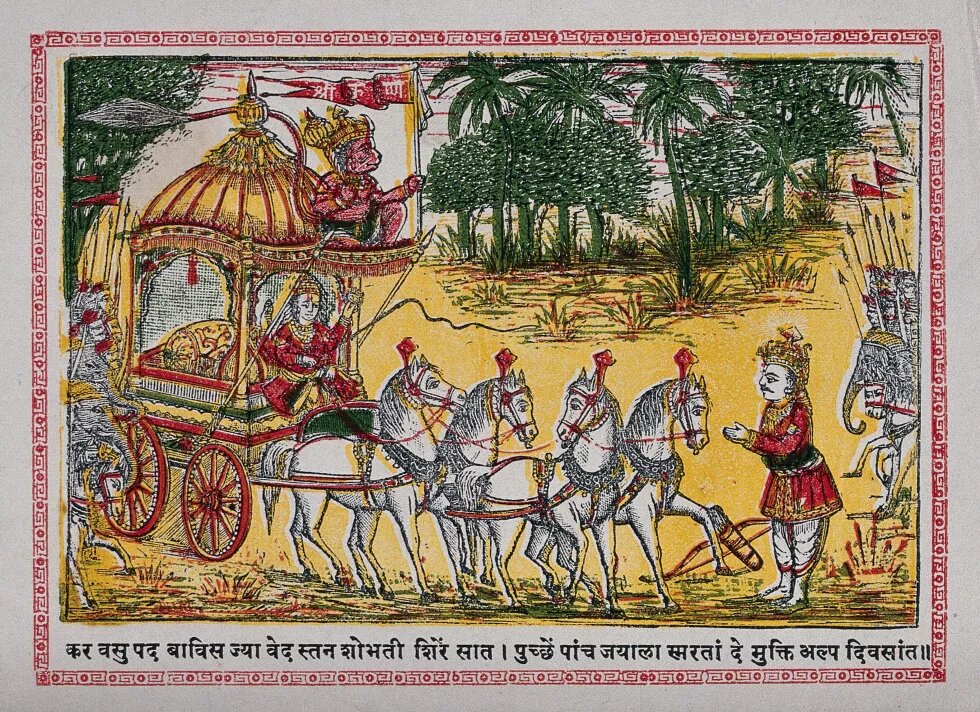

In the Mahabharata, one of the two Sanskrit epics from the Indian subcontinent, which narrated the great war between the Pandavas and Kauravas, is the story of Princess Amba who became Shikhandi in another birth. Through rebirth, subsequent cross-dressing, and ‘sex change’, Shikhandi plays one of the decisive roles in the outcome of that great war and a turning point in the epic. Amba, who was the eldest daughter of King of Kashi, was abducted from her Swayamvara (a ceremony in the ancient Vedic period, held for marriageable girls to choose their grooms) along with her two younger sisters, by the warrior Bhisma from Hastinapur. Bhisma wanted them as wives to his younger brother Vichitravarya, the reigning king of Hastinapur who was not invited to the ceremony. Amba pleaded with Bhisma and Vichitravarya to be allowed to marry the man of her choice, Shalva, to which they agreed. Vichitravarya, thus only married Amba’s two sisters. Amba returned to marry Shalva, but he refused as she was kidnapped and therefore was not ‘chaste’ any longer. The aggrieved and hurt Amba, returned to Vichitravarya in Hastinapur, requesting him to marry her. Vichitravarya declined to marry her this time since she had already refused him earlier and had proclaimed that she was in love with another man. In desperation, she turned to Bhisma, but he could not marry anyone, as Bhisma was bound by his vow of celibacy given to his stepmother. Blaming Bhisma for the misfortune that befell her, Amba vowed to take revenge. She invoked Lord Karthikeyan, the God of war. Lord Karthikeyan, gifted Amba with a lotus garland and said that any man who accepted the garland would kill Bhisma. But no one accepted the garland to help as Bhisma also had the boon of ‘choosing his time of death’ received in lieu of his vow to celibacy, and therefore was invincible. The sage Parasuraman agreed to try but failed to kill Bhisma. Amba, then went to the forest performing austerities, invoking Lord Shiva, the destroyer. The only thing she wished from Shiva, was the boon of manhood, as she believed that would make her more skilled in taking the revenge. Shiva granted her the wish but said she would be the cause of Bhisma’s end in her next life. Amba hastened her next birth by self-immolating herself and was re-born as a daughter to king Drupada and was named Shikhandini. King Drupada who was promised a son by Lord Shiva, decided to bring up Shikhandini as a boy and to be trained as a warrior. At a marriageable age, Shikhandini was married, to a princess. On the wedding night, however, the bride discovered that Shikhandi was a woman and she ran away to her father. The father of the bride who demanded proof that Shikhandini was a man, threatened to attack King Drupada’s kingdom with an army if it was proven otherwise. Shikhandini humiliated thus, went to the forest to end her life but was saved by a forest spirit, Sthuna. Sthuna on learning of Shikhandini’s pain – that Shikhandini was brought up as a boy and felt and thought like a man, but had a body that was of a woman – lent his manhood to Shikhandini for one night. Shikhandini could prove that he was a man and the new bride came back to her husband. When Shikhandini went to return his manhood to the forest spirit, their leader was touched by his honesty and allowed him to keep it forever. Thus, the Shikhandini became Shikhandi who was a man. Years later, during the Mahabharat war between the Pandavas and the Kauravas, Bhisma led the army of the Kauravas. Knowing that Bhisma had the boon of choosing his own time of death, Lord Krishna advised the Pandavas that Bhisma can be pinned to the ground with arrows instead if somehow, he could be disarmed. On the advice of King Drupada, an ally of the Pandavas, Krishna called upon Shikhandi, who had become a man, to lead into the battle. Shikhandi rode into the battle with the Pandavas with Arjuna, the great archer hidden behind him. Bhisma refused to raise his bow to attack Shikhandi as he did not accept the latter as a man for he was born a woman, and only men were allowed to fight in battles and any woman was not to be attacked. Taking advantage of this opportunity, Bhisma was pinned to the ground with arrows by Arjuna. Shikhandi thus fulfilled the vow taken from the previous life when he was Amba to bring about Bhisma’s end.

The soul, gender, rebirths and reincarnations

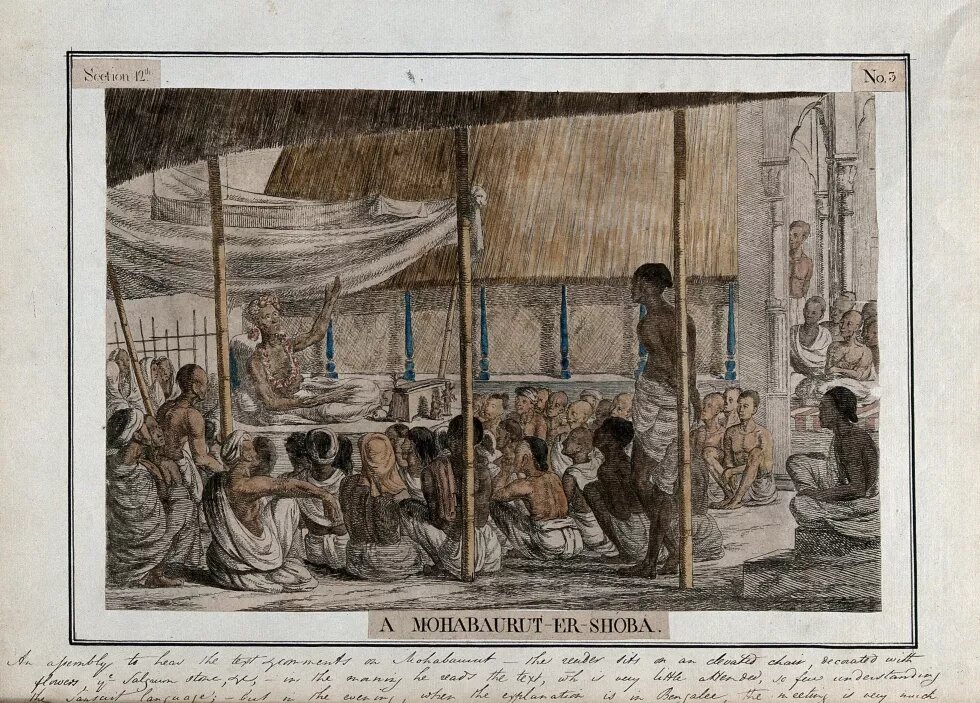

Hindu mythological stories straddle the epics of Mahabharata, Ramayana, the Puranas, regional folklore, literature, and also the oral storytelling traditions like the Mangal Kavya of Bengal, or the Tamil Periya Puranam[i]. The idea of the immortality of the soul is central to ancient Hindu mythology and therefore the soul undergoes rebirths and reincarnations. Linked to the idea of rebirth is the belief of ‘karma’ or actions that determine what one will be reborn or reincarnated as. Devdutt Patnaik, in his Shikhandi and Other Tales They Don’t Tell You, elucidates how the soul has no gender, according to Hindu scriptures; gender is only that of the body, the soul is contained in. Hindu mythology has several references to men becoming women, women becoming men, man or woman giving birth without the help of the other sex, and also references to mythic animals who were a combination of two creatures, like the makara or yali.[ii] There are numerous accounts of sex change and gender transitions, through rebirths or in the same life, and even Gods and demigods being reincarnated in a gender different than their previous form.

Stories of woman to man transgressions

Among the stories of the transgression of gender and sex change, that of Shikhandi who became a man though was born as a woman is by far the most known and uses the central belief of the cycle of life and death, karma and rebirth. Other mythological accounts of woman to man transitions, though not as known and fewer in number than those of man to woman transgressions, do exist. Another significant story is that of Chudala, the wise wife of king Shikidhvaja, who ignored her wisdom because she was a woman. The king left the kingdom in search of wisdom and retired to the forest. Chudala, who was able to change her form at will, followed her husband, taking the form of a man. As the man, Kumbhaka, she showed the path to wisdom to her husband in the day and turned into the wife, Chudala, by night.

A Bengali oral folklore tradition infers Krishna, the god of love, to be the avatar[iii] of Goddess Kali. When the world had become corrupt, Goddess Parvati, the wife of Lord Shiva, transformed into the dark-skinned Kali (Kali meaning, someone who is dark-skinned). She had descended on the earth, beheading all those who had become too corrupt. When her wrath became uncontrollable, however, the Gods sent Shiva to stop her. On seeing Shiva, she forgot her rage and love blossomed back in her, and peace and love returned on the earth. Another time when corruption became common again, Parvati was requested to go back to the earth in her previous form of Goddess Kali and fight against evil the same way. But she had a change of heart since the first episode and love was supreme now. She, instead, re-incarnated as the dark-skinned Krishna, the God, and descended on earth to change the world with love. The milkmaids of Gokul could not resist their love for the amorous Krishna and danced and frolicked around him. Shiva who missed Kali descended on earth as Radha and danced around Krishna. The combined form of Krishnakali is worshipped by some religious sects till this day, especially in Bengal and devotional songs and poems are sung for this united form; and many Kali temples worship Radha Krishna in the same complex. This folklore of Krishna as a reincarnation of Kali is in contrast to other mythological accounts, where Krishna is but a reincarnation of Lord Vishnu. The conflict between followers of Shiva, Shakti (Goddess Kali), and Vishnu in medieval Bengal was sought to be mitigated using this story with the queer theme of gender transgression of divine deities.[iv]

Downplaying of trans masculine stories

The traditional stories of mythology and folklores have passed on through generations primarily by word of mouth, as well as translations and re-writings. Retellings and subsequent translations through different time-periods have been influenced by evolving societal practices, ideologies, and also by views of the retellers. Trans masculine identities from mythology and oral folklore transitions, over time, have been mostly not given due importance and therefore, forgotten over time, and not as known in contemporary times as many of the trans feminine mythological figures are. This primarily reflects the deep-seated patriarchy of Indian society. Shikhandi was a trans masculine queer identity that has often been misinterpreted and stories like those of Chudala have been downplayed historically and culturally. The interpretations and retellings have mostly implied Shikandini to be a eunuch (castrated male) or sometimes an intersex person or even imply gender ambiguity. In contemporary times, many are still confused about the true transgression of Shikhandi from woman to man. Devdutt Pattnaik[v] observes, “Shikhandini, who became Shikhandi, is what modern queer vocabulary would call a female to male transsexual, as her body goes through a very specific change genetically. But retellers avoid details and tend to portray him/ her either as a eunuch (castrated male), a male-to-female transgender (a man who wears women’s clothes as he felt like a woman), an intersexed hermaphrodite, or simply a man who was a woman (Amba) in his past life. It reveals a patriarchal bias even in the queer space.”

Ruth Vanita is of the view that in Hindu mythology, “women are rarely reborn as men”.[vi] Amba, though she wanted the boon to obtain manhood, is reborn with the physical attributes of a female and not that of a male. This can mean that patriarchal bias existed even when these stories were being created. And interestingly, the transformation of woman to man has mostly happened to please the other partner in love and marriage, in the case of trans masculine characters in mythology and folklore. In many instances, this narrative pattern is seen in modern times too, in marriage between two women, according to the author.[vii]

In contrast, trans feminine characters appear on more frequent occasions, in the ancient historical stories and folklores of Hinduism. Many of them narrate reincarnations or transformations of Gods who took the form of women. Lord Shiva, in Ardhanarishwara form, is half-woman; Lord Vishnu turns into Mohini to enchant Bhasmasura (a demon) and save the Devas (Gods); Lord Shiva turns into an old woman to help deliver the child of a devotee and in one of the lore, Lord Krishna dresses like a woman to pacify Radha. The story of Goddess Kali transforming to Krishna, according to folklore from the eastern part of India, could be the lone example of trans masculine divine transformation. Being the reincarnation of Gods perhaps gave more credence of divinity to the trans feminine people and trans women and, therefore, greater visibility in the religio-cultural space of the Indian subcontinent. Trans women have been more recognised in Indian culture, and Aravanis, Jogappas, and Hijras claim their origins from the divine manifestations. To this day, the trans women of Tamil Nadu call themselves Aravanis, the wives of Aravan who was the son of Arjuna and the serpent princess of Mahabharata. According to a Mahabharata tale, Krishna married Aravan after turning into a woman named Mohini, to fulfill the latter’s last wish, before Aravan was sacrificed by the Pandavas to win the war with the Kauravas. The Hijras (trans women) invoke Bahuchara-mata, another goddess from mythology during their ‘nirvana’ of castration ceremony. This religio-cultural acceptance partly, has had an effect and made trans feminine persons more visible in our society, and possibly been the reason that they are invited to auspicious ceremonies like marriages or child naming events.

Way forward

The patriarchal and heteronormative social systems that have ignored and suppressed trans men and persons with trans masculine identities in India can be fought with evidence that have historical and cultural roots. The little historical and mythological narrations and evidence of trans men that are available have been interpreted based on patriarchal understandings and some stories have failed to recognise their existence. Trans men have been misunderstood rather, as being lesbians often, again reflecting, perhaps, the society’s disinclination towards recognising someone who has been assigned female at birth to be a man. All this has led to the public psyche being largely ignorant about the existence of trans men. Most people in society equate transgender with only trans women even to this day. Therefore, claiming their place in Indian mythology by trans men is, crucial to remind the society that historically trans masculine people existed and anecdotes were told.

Endnotes

[i] This article deals with mythological references from Hindu traditions, though related mythology of Jains and Buddhists also exist. It also refers to a few stories only, and there are other stories of sex change of woman to man, in folk tales or other sources.

[ii] Patnaik, Devdutt. 2014. Shikhandi and Other Tales they Don’t Tell You, Zubaan Books and Penguin Books India, Gurgaon.

[iii]Avatar is the incarnation of a deity in bodily form

[iv] Tantric or ritualistic traditions of Hinduism also talk of Krishna being a reincarnation of Kali.

[v]Patnaik, Devdutt. 2014. Shikhandi and Other Tales they Don’t Tell You, Zubaan Books and Penguin Books India, Gurgaon.

[vi] Vanita, Ruth. 2008. Introduction: Ancient Indian Materials, In Vanita, Ruth, and Kidwai, Saleem (edited), Same Sex Love in India, Penguin Books India

[vii] Vanita. 2008. (n vi)