At the end of March 2022, Shanghai was plunged into surreal silence, and scarcity. The country’s strictest Covid-19 pandemic lockdown lasted for two months. Never, since decades, had the people minded their three meals that much, to the extent of becoming the only thing they cared about. In their struggles for self-sufficiency and survival, group buying came to rescue. Did dwellers find a new sense of community or were they more fragmented?

Group buying is a business model first popularised by the American e-commerce startup Groupon, which was founded in 2008 to connect subscribers with local merchants by offering activities, travel, goods and services. The rationale is that if a certain number of people sign up for an offer, it could reduce risks for retailers, who then regard the coupons as quantity discounts as well as a sales promotion tactic. This business model was adopted by Chinese internet startups in early 2010s.

In early 2020 when the coronavirus first hit, group buying took a new turn in some Chinese cities, where most brick-and-mortar shops were closed and people were asked to stay at home. While non-food goods could still be purchased and delivered (often with a long delay) via online shopping sites, daily food and necessities became hard to come by. As a way to maintain self-sufficiency, some people with connections to suppliers, among whom were local farmers, began to use community WeChat groups, which – prior to the pandemic – were usually created by property management companies, to help solve the problems. Either the supplier who was invited to join the group or some point persons who were affiliated with the suppliers, would initiate a word chain listing the items available for purchase and people who wanted to purchase them can just add their name and preferred quantities before the deadline set by the point person. Normally, the orders would be delivered to the compound’s gate the next day for self-pickup, and the point person is responsible for distributing the goods to individual households.

This new initiative became so popular across China in recent years that a new term was coined – “community group buy” 社区团购. However, it had never grown into a trend in Shanghai prior to the lockdown. Retailing in this city is so well-developed and convenient that people are used to shop physical outlets downstairs or a stone’s throw away. Also Shanghai never had a large-scale lockdown since the beginning of the pandemic and had been relatively successful in managing the number of Covid-19 cases, until the spring of 2022.

A citywide lockdown, along with drastic suspension of all transportation and last-mile delivery, put the metropolis and its 25 million inhabitants at stake. Shanghai’s market-based economy gave way to a highly controlled management. With only a handful of companies chosen to be “legitimate” suppliers and acquired special permits needed for delivery, Shanghai citizens had no choice but to resort to group buying for survival.

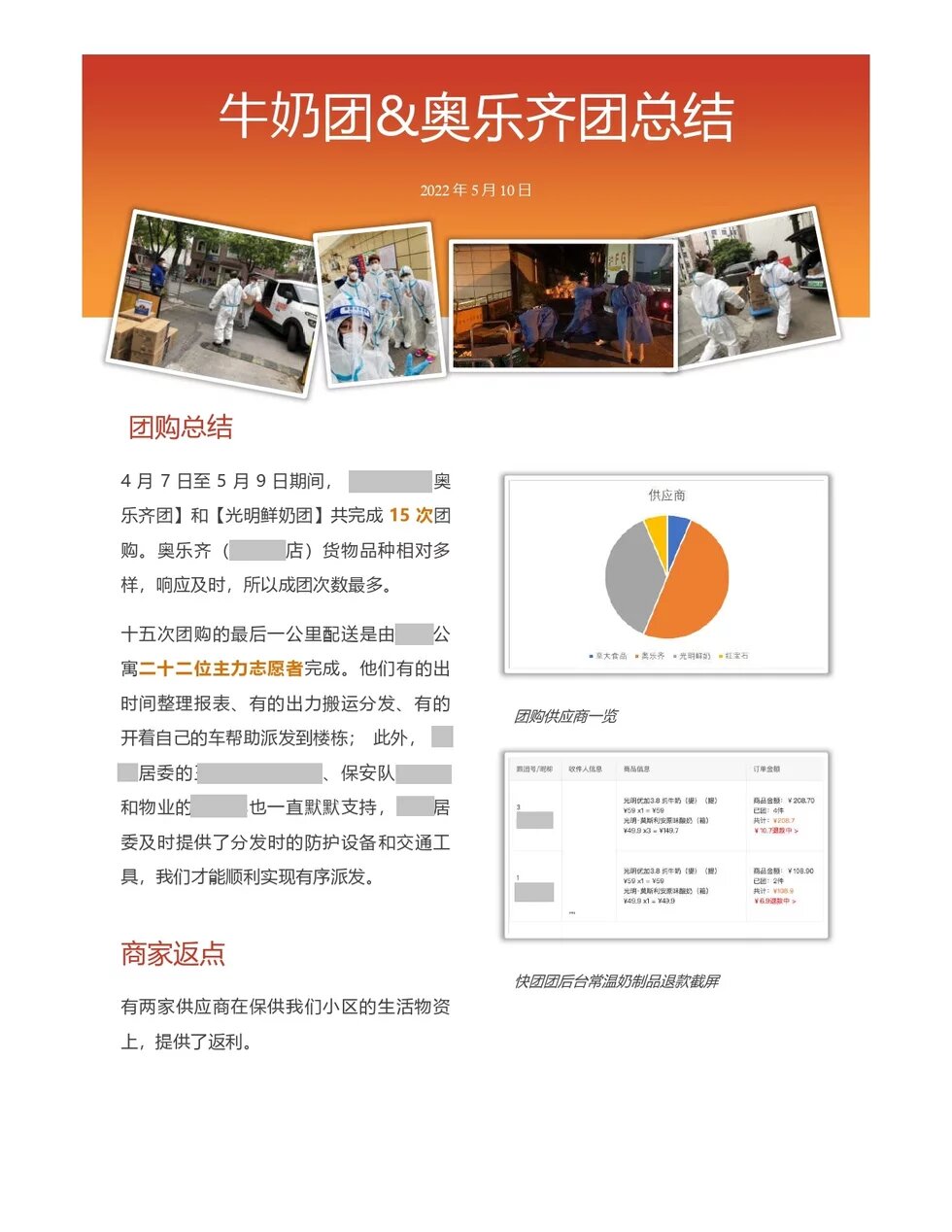

Each community, organised by its property compounds, has one WeChat group which connects all dwellers including landlords and tenants. Sub-groups have also been created by categories such as a fruits group, a milk group, a steak group. Each group has a point person, mostly a volunteer, whose job is to contact and coordinate with suppliers for logistics details as well as to collect purchase orders and payment from neighbours.

It’s not an easy job. Helena, a friend who volunteered for four sub-groups, found the coordination between suppliers and neighbours so time-consuming that it was almost like a full-time job at an IT company. She had to bookkeep every transaction and submit the compiled records to the community committee at the end of the lockdown after having the numbers “audited” by professionals and publicly shown to all members in the groups.

Thanks to digital technology and e-commerce business that China has developed for two decades, neighbours who have never met before were thus brought together in the same group and got to know each other. Bound by the shared challenges and circumstances – food and endless Covid-19 tests, it’s a new experience both for the old and younger generations. The old generation who might have stayed offline must now learn to rely on smartphones and WeChat, while the younger generations, who most often were newcomers and used to living independently, got to experience a community life and a refreshing neighbourhood bonding.

Helena, for instance, once lived in Shanghai’s former French Concession where history and information about the area is quite accessible. She moved to her current neighbourhood in Southwest Shanghai several years ago. The area used to be a farming land, and many of the landlords in her compound had been farmers previously. She had wanted to learn about the neighbourhood but couldn’t find ways to. Now that everyone was in the same group, she managed to get acquainted with some local senior residents to learn about the history and interesting anecdotes.

Another friend, Chen Jibing, a Shanghai native and longtime editor/writer for local publications, won a special victory together with his neighbours during the lockdown: they managed to evict the property management company and the head of the owner committee. As he explained, due to the lockdown, everyone had to stay home and suddenly had a lot of time to attend to things they wouldn’t have time or energy for otherwise. It was right at the time when the property management company’s term was expiring. Having been unhappy with the company and the committee for a while, residents united and worked together through a WeChat group, and finally succeeded in replacing the management company and the owner committee head.

Others went back to the old-fashioned barter trade system – trading a piece of meat for a can of Coke, or a litre of milk for a pack of eggs. A software engineer working for a big e-commerce company who lives alone in Shanghai told me that he didn’t cook at all but managed to eat a lot of chicken, because two young women living in the same building traded cooked chicken with him for cans of Coke, which became a luxury and ersatz currency during lockdown.

Indeed, when Shanghai was locked down and many inhabitants considered themselves being thrown into the worst-managed and most unbelievable situation, where people were suffering from unnecessary hungry, limited access to hospitals because they were not allowed to leave their home or enter hospital without PCR-test results. What’s worse was that no one could be sure with when the lockdown would end, which originally was set for four days but only indefinitely extended. At the end of the day, regular citizens needed to support each other so as to shine on the more human side of society. For example, some helped the elders who lived alone without a smartphone or any idea about group buying; some gave a hand to migrant workers who were often neglected by their community committee whenever it came to food allocation.

The solidarity didn’t stop at food distribution, as Chen Jibing told another story. One day a neighbour had a heart attack and his family didn’t have a car. They sent a message to the community WeChat group crying for help, after which everyone geared up immediately: “Let’s get him to a hospital quickly”. A task force was quickly assembled – who is arranging a car, who is getting the gate exit permit from the community committee and so on. In less than an hour the neighbour concerned was transported to a hospital. He has been recovering since.

Of course, in normal hours, this shouldn’t present a problem – the family could easily get a taxi and no special permit would be needed to get out of the compound. But when normal social and business systems stop working due to external circumstances, “the connection based on how physical proximity increased, like going back to the traditional acquaintance society,” said Chen.

The new-found connection might sound a bit contradictory to what digital technology is supposed to serve: to break and go beyond the physical and spatial boundaries to connect people with shared interests virtually. People connect with each other through their interests and values, no matter which city or country they are from, regardless of their nationality, age or gender. Digital tools, such as social media platforms or blogs, have allowed various connections to thrive, even though they haven’t met or may never meet in life.

The Covid-19 pandemic in China, on the contrary, has brought people back to their neighbourhood community for an unexpected reason. Residents needed to work closely together so that they can feed themselves and struggle for another day. The perfect example of merging the virtual and the physical realms with technology in extreme times was seen in Shanghai.

However, would this present a new social fabric? The answer might not be that obvious.

Shanghai is no doubt a unique case. The suspension of all transportations and last-mile deliveries, which had caused shortage of all living supplies, was never implemented anywhere else in China even though some cities, such as Shenzhen and Chengdu, also experienced citywide lockdown later on (with far shorter time). The type of bonds among neighbours in Shanghai, made possible with group buying and other responsive actions by citizens, also didn’t happen at the same level in other cities. However, regardless of the situation, technology is always the foundation for social changes and the evolution of human history. But the process usually takes a long time, decades, or even centuries, if you think about the evolution from an agricultural to an industrial society, to the high-tech Internet society where we are in now.

However, if the social fabric is changed drastically within a short period of time, the cause is usually not technological, but political.

To put it in context, China is a latecomer and follower when it comes to technological advancement and the change of its social structure. The urbanisation process China embarked on since the 1980s (with a huge jump after 2001 when China joined the World Trade Organization) emerged in the West 100 years earlier and accelerated after World War II. Yet the side effects of urbanisation in China are way greater than that in the West in terms of weaker inter-community connections and more discernable distrust and indifference among people. Compared to the image of a traditional “big” Chinese family, families of smaller size are not only a result of urbanisation and technology development, but also a direct result of the country’s one-child policy.

On the other hand, the impact of technology weighs bigger and faster on China than in other parts of the world. China’s e-commerce is more advanced than most developed markets – not because the country first invented it, but it had an easy start due to the differences in its business and legal systems. The 2003 SARS pandemic played an instrumental role in the consumers’ shift towards online shopping domestically.

Technology is a double-edged sword. While it increases efficiency and connects people in ways that would have never been imagined, it also gives the government a leg up on tightening social control. As the pandemic evolved, the Chinese government has

doubled down on the zero Covid-19 policy for almost three years. As long as there were Covid cases – even a single one – tracking, quarantine and lockdown measures were imposed. Without digital technology, it would have been hard for the government to implement the zero Covid-19 policy as it entails massive data collection, tracking and analysis for a substantial period of time, especially given the vast scale of the Chinese population and territory.

Such virus-control efforts have filtered into everyone’s life in almost all aspects, whether to take public transportation or visiting a shopping mall. The digital technology made it possible, yet the cost has been high, so has the damage on economy and livelihood. Even worse, sometimes it is abused for social stability purpose, as in the case of the Henan bank crisis in central China. In April 2022, some depositors from the five town-level banks in the Henan province found they could not withdraw or transfer money. They spread the word online and triggered thousands of depositors from other cities and provinces to visit the bank branches. The local government arbitrarily, also unlawfully, turned the health QR code of these depositors’ red so as to prevent their entry into the province. For some more time, one could only travel when his or her health QR code was green.

By the end of 2022, the zero Covid-19 policy and its mechanisms have finally come to an end. After the two-month long city-wide lockdown was over at the end of May in 2022, Shanghai citizens might have returned to their normal life, but psychologically it will never be the same. Group buying is no longer needed. Helena did a survey in one of the sub-groups she managed to decide whether to keep the group or dissolve it. To her surprise, 98% respondents said they wanted to keep it.

The same happened to many group-buy groups. Although members of the group are no longer as active as before, they sometimes use the group for the exchange of daily necessities or help each other out on small things.

“If you ask me what I would like to carry on from the lockdown experience, it’s the bond and connection among neighbours”, said Chen Jibing.

*This article is a part of Perspectives Asia #11: Transitions

This article first appeared here: hk.boell.org