This article follows the journey of transgender individuals who have made Bangalore their home, migrating from the hinterland, and a neighbouring state, and how they have come into their own agency.

The ubiquitous sambar[i] at numerous South Indian restaurants in Bengaluru – the capital of Karnataka and India’s IT hub – varies in taste and methods of preparation, ranging from sweet to spicy to extra spicy, with or without grated coconut or variation of vegetables added, and these – very often subtle and sometimes obvious – differences in taste has been hard to miss for a migrant like me. The differences are due to the tastes and culinary traditions the migrants from the neighbouring southern states have brought with them, each having distinct ways of preparing their sambar. One can find authentic, original cuisine from any part of the country in today’s Bengaluru – called Bangalore till 2006 – showing how the city has attracted people from other regions of the country and not only from its adjoining neighbours, over the years. The ever-evolving foodscape of the city is one significant testament its multi-culturalism and multi-ethnicity that it has come to represent.

It will not be off the mark to say that the city came into existence and grew in its initial stages because migrants from neighbouring states made it their home. Its founder, Nadaprabhu Kempe Gowda’s call to traders and craftsmen from neighbouring areas in 1537 continued during Tipu Sultan’s time. It witnessed large scale migration in three distinct waves since its foundation. First, when the British established their cantonment here; then when public sector undertakings were launched following India’s Independence attracting larger waves of people from primarily southern states and other Indian states too; and finally, in the aftermath of the globalisation and liberalisation of the Indian economy in the 1990s, which made Bangalore the back office of the world, and flourishing base for the IT sector[ii]. The pleasant weather throughout the year, the IT and BPO industry and the tertiary job market it opened up have made it one of the most attractive cities for migrants in recent times and has made the “Silicon Valley of India” truly a global city.

More than 50 percent of the population of the cosmopolitan are migrants.[iii] Kannadigas from other places in Karnataka constitute the biggest group of migrants followed by those from the neighbouring states. Migrants from other states are primarily from Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana and Kerala. Some of the Tamil, Telugu and Malayalam speaking people are second or third-generation people living in the state. Most of them are polyglots and can converse in Kannada, Tamil, Telugu and Malayalam.

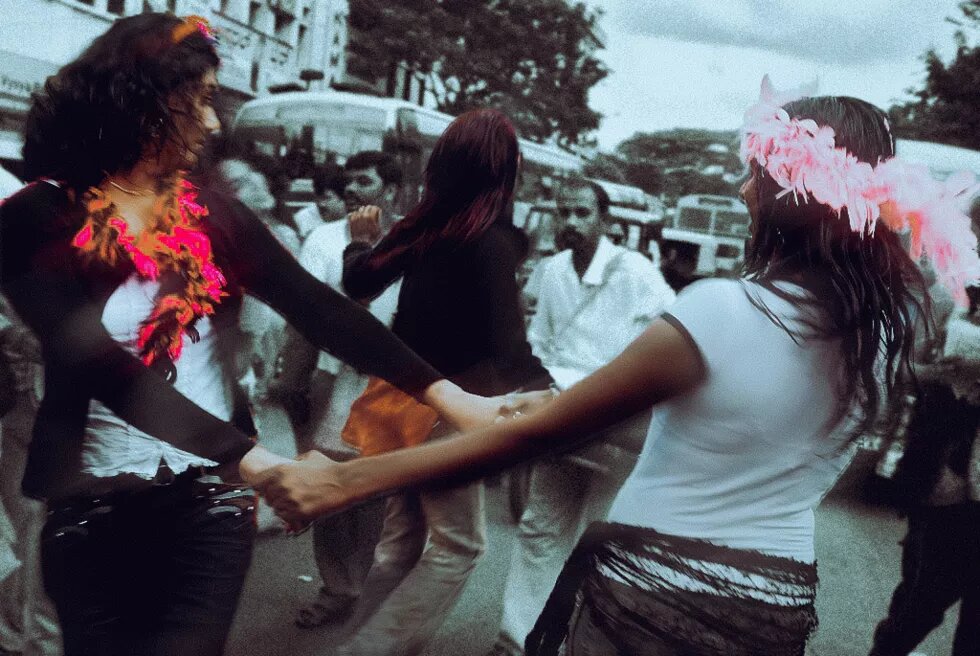

It is not surprising, therefore, that the growth history and demographic fabric has made the city very liberal and less prejudiced in its outlook. It is this open-minded environment that has also appealed to the LGBTQI (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and intersex) people from outside the city to come to Bengaluru. They have found support from the liberal minded straight people and young students. It has always been at the forefront of the country’s LGBTQI movement. It was the only non-metro city, to host its first PRIDE March in the same year as metros of Delhi and Mumbai in 2008. It has attracted and continues to be a safer city for different gender and sexual minorities who have come to call it their home[iv].

The city has attracted transgender migrants fleeing abuse and trauma from their hometowns and has been the witness to and cradle for the politics and network of the transgenders not only in Karnataka but in other states of South India. The city has nurtured the collective voice of transgenders, spearheaded by organisations like Sangamma, which started its work around the HIV-AIDs and related health interventions and has now grown bigger in perspective encouraging the birth of other groups and organisations like the Karnataka Sexual Minorities Forum, Karnataka Sex Workers Union, to name a few.

This article follows the journey of two trans* individuals, Mallappa S Kumbhar and Kiran Nayak, who have made Bangalore their home, one migrating from the hinterland of Karnataka, and the other from the neighbouring state of Andhra Pradesh, and how they have come into their own agency. Their amazing journeys, their struggles efforts to be heard, how they have integrated the voices of others and now made significant space for the transgenders in South India, negotiating and working with the authorities and society for their entitlements give a picture of the course of their path within the larger queer body politics and intersections with other movements like that of the sex workers and the disabled.

Mallappa S. Kumbhar

My name is Mallappa and I identify myself as a transgender. I am originally from Belgaum district in North Karnataka, but for the past 15 years I have been living in Bengaluru. Currently I am associated with Karnataka Sexual Minorities Forum (KSMF) and also work in collaboration with various community-based Organisations (CBO) and nongovernmental organisations (NGO) working with LGBTQI issues.

From my childhood, I liked dressing up like girls, in bangles and dresses, and also doing chores like grinding flour and sitting in the posture that women usually sit in. I preferred playing games such as kunte belle (hopscotch) and skipping with girls. By grades 6-7, I started developing romantic feelings towards boys.

I dropped out of school as our financial conditions were not good and then after my father passed away when I was in my teens, the entire family’s responsibility fell on me as I was the eldest among siblings. I started doing contractual work such as masonry, laying the electricity poles and fixing street lights for the Karnataka Electricity Board, and also worked as a part time cook in other people’s houses and in marriages.

As I feared that revealing my gender identity might affect my family who were dependent on me, I tried my best to control it. The turning point in my life came when HIV prevention programmes started in Belgaum during 2005-06, under the Karnataka Health Promotion Trust (KHPT). In 2005, I came to Bengaluru and started working as an interviewer for their Bengaluru office. My earnings helped me to get my younger sister married. When my relatives started pressuring me to get married, I avoided by giving the pretext of burden of heavy loans on me.

I worked in the HIV programmes of KHPT as an interviewer as well as field coordinator and travelled a lot. I earned enough money if I worked for three months, and then travelled all over Karnataka for the rest of the year. I had developed a network across the state and, therefore, activists asked me to join the Karnataka Sexual Minorities Forum (KSMF), which was created in 2008. I joined KSMF as a zonal coordinator in 2010. My role has been till date to identify the problems of transgenders in the districts of Karnataka, like harassment by police and issues of transgender with family. I am focused towards crisis intervention to address transgender issues.

Though I joined transgender rights activism in 2010, I did not have the optimal situation to share about my own trans identity to my family. I wanted to go for sex-change surgery but did not do it. It was not a sacrifice but a responsibility towards my family as they would have to face many questions from relatives otherwise.

With time, I learnt how to balance my responsibility towards my transgender community as well as my family. Just like as an activist, we negotiate with the society, in personal life we need to negotiate with the family and sometimes intimidate them, so that we don’t become victims of forced marriages. When I moved to another town for my work, my mother and siblings started doubting my gender orientation as I began making transgender friends on social media platforms. But as they depended on my earnings, I kept telling them: “I am working and you need money, so please don’t ask me to get married.” My family finally realised that if they did not accept me as I am, they would not have my financial support. This kind of situation is quite common for working class transgenders, and their families; though the families do not accept the transgenders outwardly, they do not protest either.

The year I joined KSMF, it was also registered formally and a massive rally was organised in Hubli to mark its inauguration. As I had contacts through my network all over Karnataka due to my earlier work with KHPT, I was able to invite people from all over the state. This event intended to increase the visibility of our community and we spoke about sex, gender and sexuality. We had invited community members as well as political leaders as guests but political leaders did not turn up. Transgender community members were joined by activist leaders from other movements such as Dalit and women’s movement in that programme. The inauguration programme was followed by a massive rally which to showed our strength in numbers, that we exist and we are part of this society and we too have rights.

The same year, the work responsibilities of KSMF increased manifold with two developments. A Government Order was passed to provide ration cards and pensions to transgenders. At the same time the government introduced Section 36A of the Karnataka Police Act[v], which gave arbitrary powers to the police to control ‘eunuchs’ and their activities, which they thought was ‘undesirable’. We were negotiating with the government on both these matters and at the same time we were also organising the “Transgender and the Law” programme across Karnataka. The law programme was organised in 2011 under the guidance of the then Chief Justice Manjula Chellur, who was also the Chairperson of the National Legal Services Authorities. Panel discussions were organised with academicians, medical professionals, psychiatrists and community members in five cities across Karnataka, namely Shimoga, Bellary, Kalburgi, Mysore and Bengaluru. In these panel discussions, the district judges from the respective district participated. These panel discussions largely contributed to our movement and laid the foundation for our future path.

The government order mentioned earlier outlined such provisions as housing, pension, self-employment loans for transgender community and proposal to identify them as backward class. But most of the provisions have not been implemented yet, except some members of the community receiving loans and pensions. Due to this order, approaching various departments for the implementation of the provisions mentioned meant our advocacy work got new impetus. The government appointed the Women and Child Development Department as the nodal department to implement the government order. But the department was not aware of who belonged to this community and only identified those transgender persons who wear sari, that is, only trans women, and did not know about trans men, Jogappas and pant-shirt wearing Kothi[vi]. The department appointed KSMF as the nodal agency to identify the people of different transgender identities. I was part of KSMF’s team to identify and certify whether a person is transgender. This certificate acted as an ID for the transgender persons who could then use it for availing any government schemes specifically made for them. The schemes that were finally implemented were: provision of a subsidised loan of Rs.20,000, which is a one-time amount and a pension scheme of Rs.500 per month. This system of certification was before the landmark NALSA – National Legal Services Authority versus Union of India – judgement of the Supreme Court, which did away with the need to get any such certification and gave the right to transgender to self-identify their gender.

Simultaneously, we also started public actions, events and dialogues on Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, which criminalised unnatural sex and, therefore, in extension meant criminalised the LGBTQ people in the country. In November of 2013, 13 people were arrested in Hassan in Karnataka citing Section 377 and false cases were filed against them. We staged a major protest against the arrests. KSMF and Aneka jointly did a fact-finding exercise where I was part of the KSMF team and a report was released. We held dialogues and discussions with police and spoke to the Superintendent of Police (SP) of Hassan to sensitise the police.

The Supreme Court order in 2012 on Section 377 of the IPC where the court re-criminalised the community had shocked us. We felt betrayed when the court asked the community to seek the support of the Parliament. This was very scary as there were very few Members of Parliament (MPs) who spoke about sex and sexuality at that time and had any awareness and empathy. Though this judgment was against us, we were not demoralised. We got support from the other movements and groups like women’s groups, Dalit groups, minority groups and labour movements and these groups stood with us at that juncture. Because of their support we could challenge the judgment on Section 377. As individuals too, we started speaking openly about our identity, saying “I am a gay”, “I am a lesbian” and “I am a trans person”. At this juncture, the KSMF decided that community representatives should go and speak to local MPs. So, we went and met the MPs in their constituencies to make them aware of us and to inform them that we are also their vote banks. We also showed that we are not just sexual minorities but we are also supported by other marginalised groups and communities such as women’s groups and Dalit groups. Besides, we met various political party members and started our advocacy work with them. We continued our activism against Section 377, focused on our districts to strengthen the movement and organised Freedom Walks.

The issues of sex workers and sexual minorities are the same. Now whether trans sex worker or woman sex worker, we work together with mutual understanding. One of the major problems that they shared is they were not allowed to do sex work in their usual area of Bengaluru and we accompanied them to the police station to speak and negotiate with the police. If a protest is organised, then we join their protest to show our support; the rights that women sex workers have is applicable for transgender sex workers too. We collectively speak about their issues common for both groups of sex workers.

A major challenge KSMF has faced in its work is that of funds and this is mainly because the members of the forum are from a working class ‘non-English’ background with low educational levels. It could get funds only when an NGO supported it and wrote a proposal for it. Till 2016 the KSMF worked with an NGO. We felt restricted and were not able to work freely; we finally had to leave the support of that NGO as we thought it would be in our best interest. After becoming independent, KSMF faced many challenges. People came into conflict with us questioning our transparency, democracy and we were also lacking in funds. Seeing our work, the Fund for Global Human Rights backed us and supported KSMF’s activities in 2017 but we still continue to face funding issues. Organisations like ours cannot approach institutional funders, who support only if one has met certain criteria, which are difficult to meet. We urge such funders to have lenient and easier rules for collectives like us.

Since 2019, KSMF has been completely working voluntarily, as there is no financial support. Due to the support of other organisations like Aneka, Rahi and Samara, we are able to carry on with our work. We organise joint events with like-minded organisations and that’s how we get space for KSMF.

KSMF has worked on different community identity issues such as on trans men and we also supported Aneka to conduct a study on the Jogappa community. We focused on different community identities in our advocacy work and the goal is to take all the identities together. The primary objective of KSMF is to prevent the stigma and discrimination faced by our community based on their gender and sexuality as well as to create an enabling environment for our community. KSMF’s work is not limited to a single district. We focus on entire Karnataka and wherever problems we intervene and work wherever there is some problem. On the one hand, we work on gender, sexuality, police and family violence against sexual and gender minorities, and fight for justice. On the other hand, we work for entitlements and facilities that they should get from the government. Apart from this we also need to organise events and actions for the visibility of sexual minorities to build on the public education and awareness about our community.

Kiran Nayak B.

I identify myself as female to male trans man and use the pronoun ‘he’. I have had an orthopaedic disability since childhood due to polio. My family was not ready to send me to school but enrolled me in a school after being counselled by a local school teacher. When I was in Class 7, I started feeling that I was a boy. Even before that I used to wear my brother’s shirts and pants. In school, my close friends were all boys. As I felt uneasy to sit with either the boys or the girls, I preferred sitting in the last bench by myself. I was not given any opportunity by my friends or teachers to express myself as a boy in school. This was in a village school in Warangal district of Telangana.

When I was in Class 9, I went to a women’s college in Warangal city where I had to stay in a hostel for disabled girl students. But I was not comfortable changing my clothes or staying with the girls in the hostel. So I returned to my village and completed Class 10 there. I made only one good friend with a girl named Sarita, during that time. She was also afflicted by polio like me. After completing Class 10, we went to the same college. Sarita’s house was near the college and I used to visit her often. Sarita had a sister, Kavya with whom I became friendly. After a few months, Kavya proposed to me. When I was in my final year of college in 2008, both of us went to Tirupathi Temple to get married, where the state government arranges free community marriages. There were 125 couples set to get married in the temple that day. I changed my name to Kiran and Kavya changed hers to Radhika to keep our identities a secret.

After the marriage was solemnised, Kavya informed her father about our marriage. Kavya’s father responded by filing a police complaint saying that the marriage was invalid since I was a ‘female’. Kavya and I had to take shelter in the home of one of Kavya’s cousin sister and her husband. They were supportive of our decision but they told us to surrender at the Warangal police station. But I knew that the police would not understand us. When we went there, we were made to sit in separate rooms. The SP tried to ‘reason’ with us that since both of us are ‘females’, we could not be married and suggested that we should return to our respective families. The media came to know about the marriage and about 30-40 media channels came to the police station that day. They accused us of polluting the temple premises. We were made to sit in the police station from 6 am to 6 pm without food.

However, help came from a reporter working for a TV news channel. The reporter knew me from my work as an activist participating in protests and programmes on disability issues. He was able to persuade the police to let us leave the police station on the pretext of interviewing us and with him we went to his office. Later I came to know that he was aware of different gender and sexual identities and their problems. I myself did not know about gender and sexual minorities at that time.

We were so traumatised due to the happenings of the day that we both contemplated committing suicide. As some media personnel and police had reached our village, the villagers also came to know about the whole incident and started cursing my family. I called my mother to speak to her for one last time, but my brother informed me that my mother had taken poison and was admitted to the hospital. It depressed me further and I almost made my mind to commit suicide. But just then, I received a call from Bengaluru. Manohar from Sangamma, an organisation working with LGBTQI community, had found out my contact number from the police station, after coming across the media reports. He spoke to me in my mother tongue Telugu. Manohar promised support to us and was able to convince us to travel to Hyderabad to the office of a community-based organisation (CBO), which worked with transgenders. Five people from the CBO came to Warangal to take us to Hyderabad. After about a week after our marriage, Kavya and I reached Bengaluru from Hyderabad. For another year and three months we were under the care and support of Sangamma and a group called Lesbit.

In 2010, I started writing proposals to fund my work as a community mobiliser and my first such support was through Aneka. Manohar and Sangamma helped me in writing proposals to seek funds for my work. I shifted to Chikkaballapur on the outskirts of the city, which comes under Bengaluru Metropolitan Area. Within a year, I had picked up the local language of Kannada. In the initial six months, I started identifying and locating transgender people in rural Chikkaballapur and finally formed a CBO called Nisarga with them. Nisarga worked with transgender people and got registered formally in 2011. I was with Nisarga for the initial five years. Nisarga’s work involved crisis intervention and advocating for transgenders with local political leadership and government officials. At present, I am only associated as a volunteer with that organisation.

I also continued my work for the cause of disability. I started the Karnataka Vikala Chetanara Samiti (KVS). There are an estimated 45,000 persons with disability in Chikkaballapur district where fluoride contamination is a major contributing cause for high incidences of disability. Currently, 12,600 people are registered as members with KVS, and it has an executive board of 13 members. We work on issues ranging from harassment faced by disabled persons from family members to issues of Dalit sex workers. Presently, I work as general secretary of KVS. The Solidarity Foundation supports us in training women with disabilities to become community leaders.

With regards to disability, the foremost issue is that of accessibility. Due to our campaign and negotiations with the government, ramps have been added in public buildings like government schools, anganwadis[vii] and gram panchayat[viii] offices in six taluks of Chikkaballapur districts. Three to four years of very concerted advocacy with local government, district collectors and local MLAs has achieved this result. Ramps are being added in all public places in other districts of Karnataka gradually. We now are focussing on other five neighbouring districts including Bengaluru (Urban). Another issue about which we negotiate with the administrative machinery is spending the designated amount for disability related purposes in the local budgets of administrative divisions at gram panchayat, taluk, and zilla panchayat levels and also from the MP and MLA funds. Till now, 271 disability friendly bikes have been given to individuals in Chikkaballapur due to our negotiations. This bike design now serves as a model for disability-friendly bikes to be given in other districts of Karnataka.

Crisis intervention to cases of harassment against disabled people is a crucial work that we do. I can talk about one incident. A disabled woman was raped, as a result of which she got pregnant. Due to our team work, we were successful in getting three of the accused got arrested and jailed. Furthering my work in this area, I am initiating and supporting in creating small groups called Disability People’s Organisations. There are 43 such groups in Chikkaballapur already with 10 members in each at village levels. KVS helps the members of the group in claiming reservation quota in government jobs. KVS also identifies disabled children who drop out and help them in getting back to school; 120 such kids have returned to school with our support.

Being a trans man myself I work with trans men issues as well. In 2014, I started workshops for trans men issues which evolved into the Society for Trans men Actions and Rights (STAR). Formally registered in 2019, STAR works on trans men issues in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, states which border Karnataka. I am the founder and General Secretary of this organisation. It has a seven-member executive board with more than 200 members. We have worked with other transgender rights organisations as a result of which, this year the government came out with the Telangana Transgender Policy and established the Transgender Welfare Board in September 2022. A trans man associate from STAR is now a member of the Welfare Board’s committee. STAR had fought together with the Hijra Transgender Committee in this campaign. Our advocacy work with the government on this issue has also been supported by Aneka.

In Chikkaballapur, I am connecting with those who are working with farmers, students and other groups. I give talks and presentations on disability and trans men issues in colleges and also at national level seminars asking people to respond to our crisis and issues. The media has particularly asked me why we are working on the issues of trans men in Chikkaballapur as according to them there are no trans men here. I tell them there are many of us but most do not reveal their gender orientation out of fear and stigma.

My aim is to make society aware of trans men’s identities and issues. That is because many such people do not open up, and some commit suicides. I try to reach out to college students who are disabled or are trans men and are in any crisis. I talk about my journey in talks, presentations and in interviews so that people can be reached and made aware about my work and can come to me in crisis.

The major challenge is to bring together people working in different movements for marginalised people. KVS and Nisarga work with different target groups but are trying to collaborate to support in each other’s objectives. At the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) in Geneva in 2019, I spoke about trans gender issues as well as disabilities in rural India, harassment faced by disabled women, how disabled people with no hands, or the blind, especially multi-disabled persons, could get Aadhar[ix] card. I have received over 50 awards for my work as a community leader and a social worker, including Rajyaorasasti Award by Karnataka government (2016), Dr Batra’s Health Hero Award (2018), NCPD Award by the Central Government, Deccan Herald Changemaker Award (2022). Four fellowships received from – Aneka, Solidarity Foundation, Fight for You and Women’s Fund Asia – have helped me in my work over the years.

As Mallappa explains, “Activism is a combination of person, community, organisation, family and society and we need to see these five arms clearly.” The voices of the people who do not have the means or the language to express are upheld by social workers who negotiate with different agents of the society, the governments, and the general public with grit and honesty. The testaments of Mallappa S. Kumbhar and Kiran Nayak B. show how the city of Bengaluru has given a strong foundation, and shaped and brought focus to their work as activists and how that, in turn, continue to strengthen the LGBTQI movement the city. Their stories tell us how other activists and organisations have nurtured and collaborated with those who come to the city from outside to make it their home, adding to the bandwidth of the city as one of the important centres in the map of LGBTQI movement in the country.

Endnotes

[i] Sambar is a lentil based soupy dish and a common accompaniment to rice and rice-based items like idli and dosa, the staples of South Indian states.

[ii]Arun Dev, 2021, “3 waves of migrations that shaped Bengaluru” Hindustan Times. https://www.hindustantimes.com/cities/others/3-waves-of-migrations-that-shaped-bengaluru-101615660544003.html, accessed October, 2022

[iii] TNN, 2019, “Bengaluru's migrants cross 50% of the city’s population” https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/bengaluru/bengalurus-migrants-cross-50-of-the-citys-population/articleshow/70518536.cms accessed October, 2022

[iv]Mahalakshmi P., TNN, 2018, “Bengaluru has always been at the forefront of LGBTQ rights.” https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/bengaluru/bengaluru-has-always-been-at-the-forefront-of-lgbtq-rights/articleshow/65713951.cms, accessed October, 2022

[v]TNN, 2015, “Sec 36A of Police Act violates eunuchs’ rights, says Forum” https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/bengaluru/sec-36a-of-police-act-violates-eunuchs-rights-says-forum/articleshow/49638174.cms Accessed, November, 2022

[vi] Jogappas are lesser known transgender persons living in north Karnataka and bordering areas of Andhra Pradesh, and Maharashtra who have dedicated their lives to Goddess Yellamma. Kothis are men who prefer to take feminine roles in same-sex relationship.

[vii] Anganwadis are rural child care centres in India

[viii] Gram Panchayat is the basic village level governing body in India, members of which are elected by those citizens who are above 18 years of age

[ix] Aadhar is a unique 12-digit identity number for each citizen of India.