In spite of the history of legislative reservations for women, it's essential to recognise that there may be more effective solutions to achieve women's political empowerment.

Women must be adequately represented in politics in a true representative democracy. Globally, the number of representative governments has increased, but women remain underrepresented, despite being one of the key indicators of gender equality in parliamentary politics. Globally, women's representation in national parliaments stands at an average of 26.2 per cent, with regional variations. Although India has a parliamentary democracy and a population of 662.9 million women, it has faced challenges and made slow progress toward gender equality. As India commemorates 75 years of Independence, it is vital to evaluate the multilayered challenges on the way to women’s representation in politics and policy making and explore ways to this intricate political process of claiming space and rights.

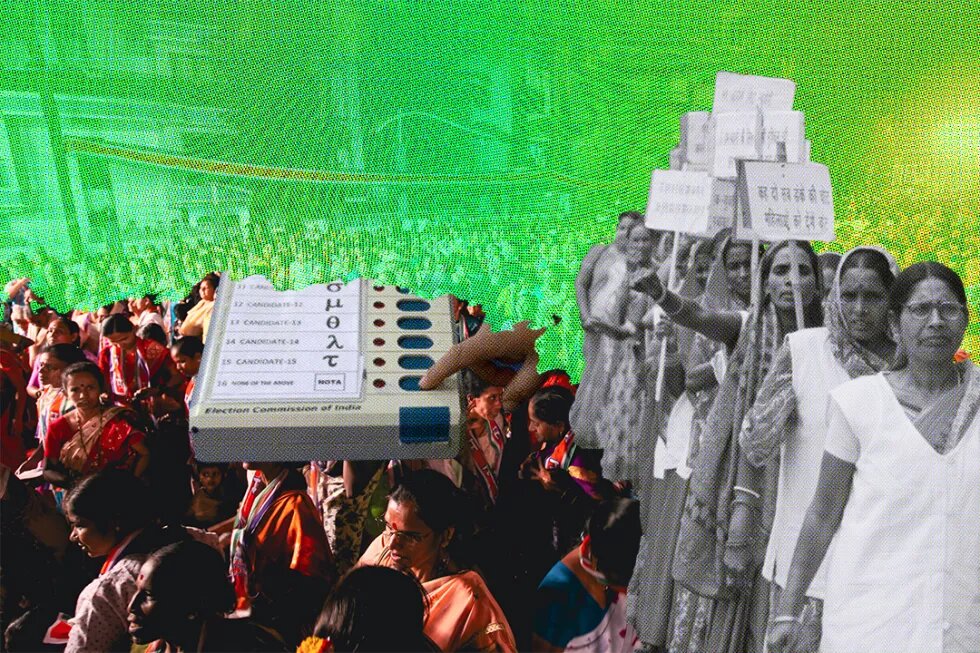

In 1992, the central government passed the 73rd and 74th Constitutional Amendment Acts, which mandated that one-third of seats in panchayati raj institutions (PRIs), a system of rural local self-government in India, be reserved for women, promoting women's participation in local government. The 73rd Amendment also advocates for reserving seats in PRIs for minorities like women, Scheduled Castes, and Scheduled Tribes. Unlike parliamentary and state assemblies, PRIs prioritise equitable distribution of public goods, especially for rural women. Furthermore, this approach attempts to translate gender parity policies into localised actions that promote gender equity. The findings of several panchayat surveys show that despite initial resistance against power sharing with women leaders, communities eventually accepted the independent roles and actions of women. A mandated reservation system has improved the representation of women and their ability to exert agency in local government. Additionally, the National Rural Livelihood Mission, a poverty alleviation project implemented by the Ministry of Rural Development, Government of India, has effectively provided capacity-building support for elected women representatives in decentralised planning and progress monitoring. Due to this, women can voice their concerns and opinions with a greater degree of political influence. There is also evidence that female sarpanchs (sarpanchs are the elected member of the village level constitutional self-government called the gram panchayats in India) increase the likelihood that women will be elected heads of villages. Today, India counts roughly 3.2 million elected representatives at local level and nearly half of them are women.

Between the first Lok Sabha (1952) and the seventeenth Lok Sabha (2019), women’s representation has increased from 4.4 per cent to 14.94 per cent of the total membership. It is argued that because of structural impediments, women remain underrepresented in national and state legislatures. Often, women are underrepresented in political parties making it difficult for them to climb the ranks and secure party nominations. It is likely that this lack of representation is caused by gender bias within political parties and that women are not as electable as men. Women's representation has a lot to do with the way their bodies and identities influence their experiences and opportunities in politics. Women are discouraged from becoming politicians because of societal norms and expectations that prioritise traditional gender roles. In some cases, it may be difficult for women to pursue political careers due to gendered expectations that they prioritise family and caregiving duties. Women's political opportunities are limited because of stereotypes and biases based on physical characteristics. Women's experiences with objectification, harassment, and gendered violence can deter them from participating in politics and create hostile environments.

The metaphor of the body politic illustrates how society is actually structured. This powerful but subtle form of politics recommends the core patriarchal principles by which society should be arranged in an ideal manner and, in particular, that a reciprocal interdependence between members is necessary as well as a hierarchy between the lower and higher members. In order to achieve greater gender equality and inclusion in politics, it is crucial to recognise and address embodied politics.

Institutional reforms are pivotal to advance women's representation in Indian politics. In spite of the history of legislative reservations for women, it's essential to recognise that there may be more effective solutions to achieve women's political empowerment. One approach is to legally bind political parties to allocate at least one-third of their tickets to women candidates. Another option is to mandate substantive reservation for women in parliamentary and state assembly seats. Both options require consensus among political parties and society. The role of women's organisations and civil society movements in advocating for institutional change and fostering women's political mobilisation is crucial.

India's legal framework guarantees gender equality, but the reality remains uneven. Cultural biases persist, with daughters often deemed an economic burden due to dowry and marriage expenses. Gender-selective abortions continue despite bans. The skewed sex ratio in India reveals the depth of this challenge.

The Women's Reservation Bill tabled in 2008 marked a historic moment in India's legislative history. Through this initiative, women sought to be more prominently represented in policy-making bodies. The proposal entailed a provision for one-third reservation of seats for women in the national and state legislatures, specifically in the Lok Sabha and state assemblies. Although the Women's Reservation Bill received substantial support from influential leaders across political parties, it ultimately lapsed due to the dissolution of the 15th Lok Sabha, highlighting the complex challenges involved in implementing legislative reservations. Over three decades later, in 2023, the 128th Constitution Amendment Bill, referred to as the Nari Shakti Vandan Adhiniyam, and its six clauses were passed with all 214 members present in the Upper House voting in favour of them. Nevertheless, the question remains as to whether there is enough political will to make this commitment a law. This delay also reflects male-dominated legislators' reluctance to address gender disparities in politics.

The 30th Gender and Economic Policy Discussion Forum (GEPDF), held on 8 August 2019 focused on representation of women in general elections. In the forum, it was noted that there are more women taking a greater interest in politics now than in the past. In addition, a few political parties are taking more proactive measures to nominate women for both assembly and parliament elections. There is a strange paradox regarding women's political participation in India. On the one hand, there are a number of powerful women political leaders; on the other hand, there are few women in the state assemblies and Lok Sabha. The forum mentioned that the voters are also partly responsible for the underrepresentation of women in the electoral process. Generally, Indian voters believe that women candidates cannot make bold decisions for their constituencies. Considering political parties' apathy to nominate women candidates in fear of losing votes, the forum discussed that the women candidates from political families receive a higher proportion of the vote than the women candidates from non-political families. The alternative narratives that support the value of women's representation in Indian politics must be strengthened in the context of low representation of women in state assemblies and Lok Sabha.

India's journey towards inclusive political representation has been gradual, marked by both progress and obstacles. Education, financial independence, and media awareness have spurred women's political participation. However, institutional barriers and patriarchal norms persist, inhibiting their access to contesting parliamentary elections. Implementing legal measures and policy changes remains crucial to augment women's representation in Parliament and state assemblies. As more women engage in politics, they have the potential to reshape governance and policy discourse, ultimately leading India closer to a truly inclusive and representative democracy.

Link to 30thGender and Economic Policy Discussion Forum