In the competition for Global South leadership, countries like Sri Lanka will look to affirm ‘neutrality’ between the two Asian aspirants, India and China, hedge their bets and exploit strategic openings.

As Asia’s two giants – India and China – ramp up their aspirations to be the voice of the Global South, countries like Sri Lanka find themselves walking a diplomatic tightrope. Both contenders are key economic and strategic partners for Sri Lanka – the largest sources of foreign direct investment (FDI) at 15 per cent each, the top two sources for imports (China 23 per cent, India 20 per cent) and major sources of bilateral development finance (China 18 per cent, India 4.4 per cent).1

Sri Lanka has cultural and historical ties to both countries that span centuries. Bilateral relations with India have had its ups and downs, and for different reasons. In the 1970s, Sri Lanka’s growing closeness to the United States (US) amid an opening up of the economy was a source of tension. In the 1980s, the spilling over of Sri Lanka’s ethnic tensions into India’s domestic politics in its southern states brought the two countries into direct conflict. But, by the 1990s, relations had warmed considerably to allow a bilateral free trade deal to be signed – the first of its kind in South Asia. However, the entry of China as a strategic partner bearing arms, development finance and diplomatic cover as Sri Lanka began a final military push in 2006 to end its armed conflict was to be a fresh source of tension once again.

Between two Asian giants

The military push was under the watch of a hawkish newly elected president, Mahinda Rajapaksa. China’s backing was critical to thwart growing international pressure to halt the war, and with its successful conclusion in 2009, Sri Lanka’s post-war development was underwritten by large infrastructure projects in ports, energy and transport with loans worth more than USD 10 billion under China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). By contrast, India was reluctant to provide any material support on the war front given its own domestic compulsions and bilateral relations drifted. Indeed, as Sri Lanka faced soft economic sanctions by Western powers and demands for accountability at the United Nations Human Rights Council, India sided with a 2012 resolution against Sri Lanka led by the US.

There was an internal and external pushback to counter China’s growing dominance in Sri Lanka. It received a boost with the ousting of Rajapaksa in 2015 by a population weary of an increasingly autocratic governance style. In the aftermath, some Chinese projects were suspended while new projects were signed with India. The latter included the development of a container terminal at the strategically located Colombo port, adjacent to a Chinese-operated container terminal built in 2014.

Increasingly too, a global narrative began to emerge that Sri Lanka was lured into a “debt trap” by easy Chinese loans as the China-built Hambantota port changed hands.2 However, there was little evidence to support this claim.3 Rather, the biggest burdens were international sovereign bonds worth more than USD 35 billion issued by Sri Lanka in the post-war era. Nonetheless, its 2022 debt default – from amongst growing numbers of developing countries at high levels of debt distress following the pandemic – did slow China’s bankrolling of large infrastructure projects.

There was a visible reset to bilateral relations with India and China in the lead up to the crisis as well as during Sri Lanka’s debt restructuring negotiations. Both countries extended financial help with official credit lines and swap arrangements. Indeed, India was perceived to be making up lost ground, leading the rescue effort with a generous USD 4 billion assistance package in total, winning the public’s gratitude in the process as fuel and medicine shortages were eased. The debt restructuring negotiations too went smoothly; despite the complex creditor mix – China, Japan and India being the largest bilateral creditors4– negotiations were wound up successfully within a relatively short period under an official creditor committee co-chaired by India, Japan and France that worked closely with China.

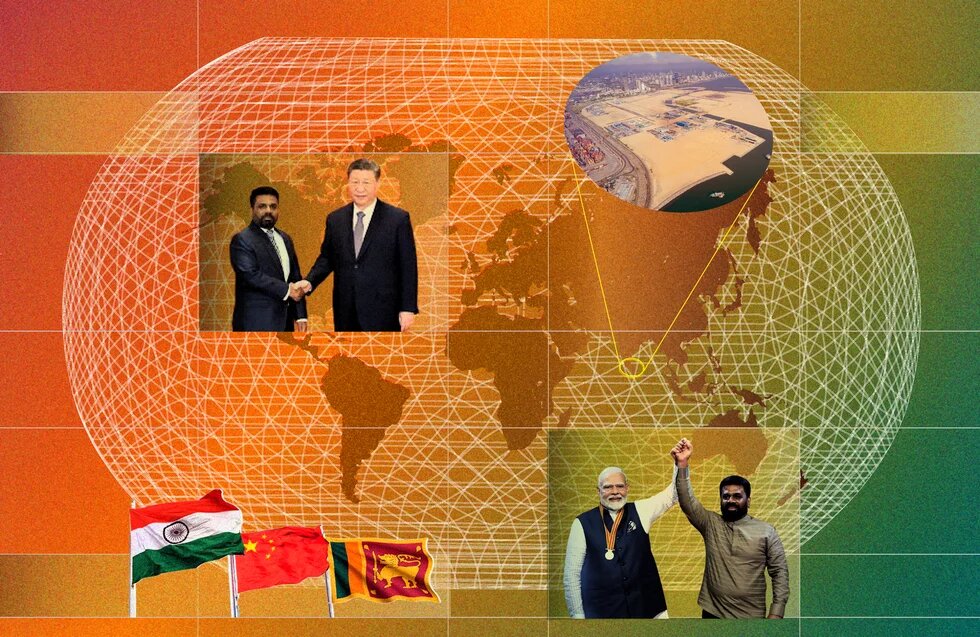

Sri Lanka’s experience suggests that there are no easy opt-outs for countries caught up in big power rivalries. Even while debt restructuring negotiations were underway, Sri Lanka signed off on crucial deals with both India and China. These included the re-start of the Colombo port development in 2023, but this time with India’s Adani Group. At the same time, an agreement to build an oil refinery adjacent to the Chinese-operated Hambantota port was signed with Sinopec. A large wind-power project, also put forward by the Adani Group in 2023, is in abeyance as Sri Lanka’s new government sought to review the deal.

Access to investment

Up against such concessions and compromises, countries like Sri Lanka will look to affirm ‘neutrality’ between the two Asian aspirants, hedge their bets and exploit strategic openings. This is likely to be even more so as the Global South regroups under the threat of intensifying trade wars and geopolitical competition, where access to finance and investment will be the priority for many.

After scaling back BRI investments, China appears to be issuing fresh contracts on a large scale once again.5China’s deeper financial pockets to deliver hard infrastructure, its extensive supply chain networks, and its partiality to a policy of non-interference on domestic issues will continue to be attractive to many in the Global South. By the same token, India’s headway in delivering soft infrastructure such as digital public infrastructure and bridging developmental gaps as its economy expands rapidly are compelling narratives to be emulated.

For countries aiming to benefit from closer engagement with both India and China, the dilemma will persist. Unsurprisingly, Sri Lanka’s newly elected president made New Delhi the destination of the first official visit in December 2024, followed swiftly by a visit to Beijing in January 2025.Geopolitical shifts under the new Trump administration adds another layer of uncertainty in this positioning.

The Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QUAD) – a strategic partnership between the United States, India, Japan, and Australia – has played a key role in shaping interests in the Indian Ocean, reflecting a joint US-India effort to contain China’s growing influence in the region. However, the punitive tariff meted out to India and the subsequent meeting between India and China as witnessed at the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation in September 2025 signals a possible thawing of relations between Asia’s two giants. If so, it should help countries like Sri Lanka but it is unlikely to be viewed as a firm turning point for their joint championing of the Global South just yet.

Footnotes

- 1

Central Bank of Sri Lanka. 2024. Annual Economic Review 2024 – Statistical Appendix. Colombo: Central Bank of Sri Lanka.

- 2

New York Times. 2018. How China got Sri Lanka to cough up a port. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/25/world/asia/china-sri-lanka-port.html

- 3

Weerakoon, D., and S. Jayasuriya. 2019. Sri Lanka’s debt problem isn’t made in China. East Asia Forum, February 2019. https://eastasiaforum.org/2019/02/28/sri-lankas-debt-problem-isnt-made-…

- 4

International Monetary Fund. 2023. Sri Lanka: IMF Country Report 23/116. Washington D.C.: IMF.

- 5

Nedopil, C. 2025. China Belt and Road Initiative Investment Report 2025 H1. Griffith Asia Institute, University of Griffith, July 2025. https://blogs.griffith.edu.au/asiainsights/china-belt-and-road-initiative-bri-investment-report-2025/