Weaving in indigenous Dimasa community of Assam

19 December 2019, by Avantika Haflongbar

Assam’s Dimasa weavers are one of the oldest indigenous communities of North East India with their rich cultural traditions and aesthetics, but sadly remain hidden from exposure. Dwindling number of young weavers and lack of infrastructure, specifically market access, supply chains and limited government intervention are a major threat to the growth and very existence of the community.

Weaving is an age old practice in Dimasa society.

Weaving is an age old practice in Dimasa society. The entire process of weaving was woman-centred in the Dimasa community, but in recent times few men have also started to weave. Expert women weavers are called ‘Daokrigdi’ and expert male weavers are called ‘Daokrigdao’. Most girls in a Dimasa family start at a young age to learn weaving from their mothers or grandmothers by observation. They can weave both complicated patterns for occasional use as well as simple and plain clothes for everyday use. According to tradition, it was essential for a girl to learn weaving before marriage. Incompetence in weaving was regarded as disqualification for prospective marriage proposals. But in modern times this is not the case anymore. It is not merely a custom to observe but a means of independence for females of the community. Weaving is a lifelong association for many. A Dimasa woman will continue weaving until her body is too old to perform such activities. An old Dimasa lady, even when not working at the loom, would be rearing eri silkworms (S. cinthya ricini). Most of her activities would be revolving around weaving. But in recent times, the majority of women who take up other jobs do not weave once they start working, except for a few who still weave because of their strong sentiment for this traditional art.

Hand-woven cotton cloth plays an important role in all the stages of life in a Dimasa community, starting from the birth of a newborn till death.

During the ritual known as ‘Nana Dihonba’, a ceremony for carrying a newly born child outside the house for the first time, while taking the baby out, the ‘hojaijik’ (first midwife) carries the baby in a folded ‘rihmsao’ in case of a baby boy and ‘rikhaosa’ in case of a baby girl.

It is customary to clothe a male or female dead body in complete traditional attire worn during their wedding and at their funeral.

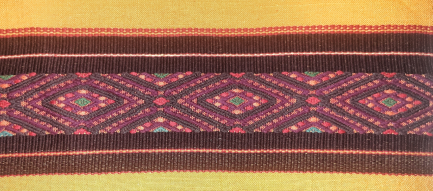

A deceased male is covered with rihmsao and a female in ‘rihjamphaingufu”. Rihmsao is a traditional shawl. It is usually woven in white or yellow colour. It has a particular design on its border.

Rihjamphaingufu is a plain white chest wrapper with a particular design.

Folklores related to the origin of weaving

It is difficult to trace the origin of traditional loom ‘daophang’ in the Dimasa community due to lack of written documents and records. The traditional folklores, folk songs, and inscriptions on historical relics have to be the main source of information. But according to the legends and stories from the elderly people, it is believed that the usage of daophang existed at the beginning of the universe, which was completely uninhabited. There was neither sound nor air. It was only filled with water and immense silence. In this midst, two godly beings appeared – a male and a female. The male God was called Bangla Raja (Father of Dimasa Gods and King of Earthquake) and the female Goddess was called Arikhidima (Mother of Dimasa Gods/ Goddess with wings of a fairy). Arikhidima and Bangla Raja later fathered seven sons. But Arikhidima was not happy with her sons because they were very simple and content in their ways despite having divine powers. None of them had the desire to neither explore more nor create newer things to make the world an exciting place. Disappointed with her sons, Arikhidima left for the most suitable place to lay her eggs. At last she found a big, evergreen banyan tree in between the confluence of two rivers, Dilaobra and Sangibra.

This place was described as Utopia, with tall big leaves and branches of the banyan tree, which could not be broken in any storm. The land beneath the tree could hold as many as 1,000 animals; equal number of birds could live over the leaves of the tree. Arikhidima laid seven eggs and flew away. After seven days, all the eggs hatched themselves. From the first egg Lord Sibrai was born. Doo Raja, Wah Raja, Gonyung Raja, Brayung Raja and Hamyadao were born out of the next five eggs respectively. The seventh egg, which got rotten, is believed to have made way for all the evil spirits, sufferings and diseases into this world. Hence, the six Gods, from Sibrai to Hamyadao, are considered to be the ancestors of the Dimasas and also worshipped as their Gods. After living a long time by them these six God brothers went out looking for their Mother. Their first few attempts to search her were in vain but one fine day while returning to their birthplace they found their Mother weaving under the evergreen banyan tree. Among all beliefs, this legend is regarded as the most acceptable theory about the origin of the Dimasas and weaving.

The monolithic hut (stone house) of Maibang erected by Raja Harish Chadra Hasnusa in the 16th century.

photo credit - Mrs Snigdha Hasnu, District Museum, Haflong,Dima Hasao. 2013-2014.

Meaning: “You came to pick me the night before yesterday but I could not go, you came to pick me yesterday too but I could not go, Rikhaosa in the loom, horai gili is yet to complete”

Rikhaosa in the loom, horai gili is yet to complete” Rikhaosa is a chest wrapper and horai gill is a design to be woven in a rikhaosa.

The song indicates the dedication upon weaving of a cloth.

Meaning: “Your cloth is new, mine too. Your’s cloth is horaimin, mine too horaimin Come friends, come friends to the village headman’s porch. Mother God has given us this day, let’s dance together. Father God has given us this day, let’s dance together.”

‘Horaimin’ is a kind of design woven on the rikhaosa and ‘khunang’ means the village headman.

The song indicates the joys of wearing new woven clothes and dancing together at the God given day at the village headman’s house.

The song is from the perspective of a third person and the singer is telling a young Dimasa girl that all the clothes that she is getting to wear is because of her mother who weaves them for her. These type of folk songs are known as 'Murithai'. The song attached has been performed by Maiphal Kemprai.

Emergence of women entrepreneurs in the economy will help in building the economic independence of the weavers, improve the status of women, promote economic development and solve the problem of unemployment. But before that we need to work on the upgradation in skill and technological know-how. Since handloom is an age-old traditional activity in all the villages of our district, each and every targeted beneficiary requires training for skill upgradation, improved looms, design support for product development and proper work shed due to their poor economic condition. At the moment, very few looms supplied by the government actually reach the weavers. Most of the times, the beneficiaries of the loom provided by the government agencies cannot even weave, which results in total administrative failure.

The loom and yarn, when given to the rightful person, will only help keep the art alive. Majority of the weavers are from the villages and very marginalised. Many villages in our district are not connected with roads and have no electricity yet in this age and time. In order to preserve the enduring tradition of Dimasa handloom against the backdrop of globalisation, government bodies and non-government bodies should rigorously equip the weavers with the required loom, yarn and updated skills. Facilitating awareness, training on product development and design development are not visible in the handloom community of the Dimasas. The need for a textile park providing all essential facilities from pre-loom, on-loom to post-loom is also to be considered. Infrastructural support on the part of the government is required. The handloom industry of Assam should help Dimasa textile to be brought under the Geographical Indication (GI) tag.

Moreover, the younger generation have forsaken the art of weaving and have little interest as well. Since many of the children are sent away to towns and cities for higher and better education, the interest or the desire to work in the loom is dwindling. Weaving community in Dimasa society is undergoing a major change. With the passage of time, the practice of making natural dyes is also declining. Of late, a handful of elderly women are practising the art of natural dyes in the district. Weavers prefer to buy coloured yarn from the market, which offers a variety of shades, whereas, natural dye has limited shades. Cotton yarns are now being replaced by acrylic, zero ply and polyester yarns. In the thick of this transitional phase, with marketing and branding skills along with the support of handloom and textile departments of the government, social entrepreneurs from Dima Hasao can revive the age-old traditional knowledge of weaving by using social media and e-marketing platforms. Challenging times are ahead for the weavers of the Dimasa community and technological and infrastructural intervention is the urgent need of the hour that will keep up local practices, giving a much needed boost to the centuries-old traditional art form.

This study was done by visiting Phrapso and Dibarai villages of Haflong town in Dima Hasao district. The methods of weaving were observed and discussed with Maimu Bathari, Kerola Naiding, Elbita Naiding, Baby Phonglo, Maiphal Kemprai, Janata Haflongbar and Minali Kemprai. All of them are expert weavers in the Dimasa community. Information was given by the elderly people of Samparidisa, Gunjung and Phrapso villages of Dima Hasao.

[1] Geographical Indication (GI) is a sign used on products that have a specific geographical origin and possess quality or reputation that are due to that region.

2. Kemprai, Maiphal 2018, Study on Dimasa Traditional Handloom. Dibarai, Haflong, Assam.

3. Kolb, Michael R 2019, Out of the Hills: Young Dimasas and Traditional Religion. Christian

Basti, Guwahati: North Eastern Social Research Centre.