A personal comic-essay mapping ways to build realms of care, and reclaim one’s body in the midst of navigating sexual violence, medical dismissal and isolation.

Content warnings: mentions of marital abuse, child sexual abuse, mental illness, dissociative episodes, anti-fatness, ableism

Becoming sick was deeply heartbreaking, but simultaneously and oddly, crashed open my life. It threw me into a starry sky littered with constellations of learnings, and radical visions that I may not have been transformed by otherwise. Like many of us, I was deeply entrenched in the ableist world we live in. My dreams included becoming the most independent version of myself, and spending all my time dedicated to work. I’d grown up seeing my mother stuck in an abusive marriage despite being the primary earner, she did not have access to any of her own money or freedom. It broke my heart every single day to see the windows of her world shrink. I watched while everyone around concurrently judged, but also urged her to never leave the marriage. So, I was certain, I could never rely on community. I had to build a life for myself that I was proud of, and do it all alone so no one could ever snatch it away from me. And then, everything shattered.

The truth is, there was no singular moment where everything changed, no neatly wrapped before and after story.

The truth is, there was no singular moment where everything changed, no neatly wrapped before and after story. My earliest memory of experiencing depersonalization was when I was five. Of course I did not have the vocabulary for it then, but I vividly remember feeling like I was existing outside my body, watching myself and life go by, like a spectator – everything felt like an uneasy, shaky nightmare that I did not want to be in. I was mostly disoriented, spent long months crying and just wanted to read the same book again, and again, and again. My hands didn’t feel like mine, my body felt like someone else’s. No one could understand what was happening. The doctors termed it anxiety and depression. Over 12 years later one midnight when I was researching for a college project, I came across the term for the first time, and it just fit. More research and rabbit holes later, I learned that there’s a strong link between childhood sexual abuse and depersonalization.1

I brought my findings to the psychiatrist I was seeing at the time. It was really unaffordable to visit one, so I was already agonizing about eating into our limited funds with my health issues. I had to keep changing them, because I’d keep getting dismissed for being highly functioning and an exceptional student, as if it was impossible to be both along with having a mental illness. As a teenager, I was confused and scared when psychiatrists repeatedly told me I was not mentally ill enough, despite having already been on medication for anxiety and depression for over a decade. While The Mental Healthcare Act 20172 states that mental illness shall be determined in accordance with nationally or internationally accepted medical standards, it also unfortunately defines mental illness as: “a substantial disorder of thinking, mood, perception, orientation or memory that grossly impairs judgment, behaviour, capacity to recognise reality or ability to meet the ordinary demands of life…”

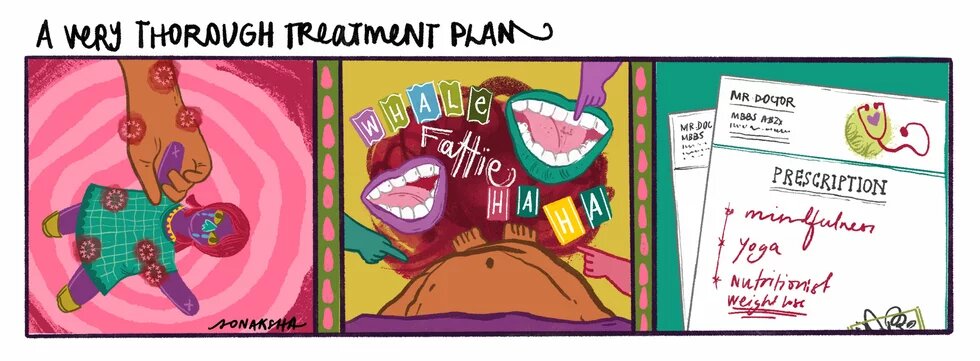

Panel 1: Illustration of a child holding a doll in their hands. There are blobs in red highlighted across the hand and doll.

Panel 2: POV Illustration of a fat child standing with their stomach being pointed at. There are laughing mouths across the image and the text reads: Whale, Fattie and HAHA.

Panel 3: Illustration of a prescription from a doctor with mindfulness, yoga and nutritionist (weight loss) scribbled on it.

If you’ve sought out mental health support, you know how disorienting the experience is. When it’s your turn on the conveyor belt of appointments, the art of learning to tell your life’s history in a 5-minute window is one you have to master: a perfect combination of important milestones, personal experiences and medication history. My current therapist keeps pointing out the way in which I mention a lot of deeply traumatic anecdotes with the casual tone of a chat about the weather, and I think I may have first picked up the habit in the process of narrating my 5-minute story to a psychiatrist. There was no time for emotions, breaking down or tears – we had to get to the point, and then the prescription. So, it was no surprise that the psychiatrist agreed with my findings, mumbled something about chemical imbalance, wrote down some medication, asked me to explore mindfulness3, meet with a therapist, and return in a few months for a review.

I left that appointment feeling frustrated. It was the first time I’d articulated years of childhood sexual abuse to someone in detail. I was spiralling in shame, and embarrassed by the stream of recollections haunting me each night. I kept telling my therapist that I didn’t feel safe enough to ground myself and explore mindfulness. I was constantly depersonalized because I didn’t feel safe in my own home, where I was still living alongside my father, my abuser, in constant fear. So, I felt untethered in my body. No dosage of medication was strong enough to account for the terror my body was living in on a daily basis. Over the last few years, we have encountered many conversations on mental health across panels, campaigns and books – but they are largely centered around the biomedical model that focuses on individuals and their bodily symptoms, while pushing for biological interventions and pharmacological treatments. Many of the psychiatrists I have visited default to the biomedical model, without an explanation of their approach or the alternatives. The biomedical model4 reduces mental illness to a brain disease, while placing a strong emphasis on pharmacological treatment and disease specific drugs, with the ultimate focus being on cure and symptom reduction. While this approach has made way for some treatments, it fails to consider crucial factors like systemic discrimination and exclusion that have compounding effects on our body-minds5. My multiple visits to psychiatrists, left me feeling like I didn’t have the autonomy to be an active participant in my healing process and furthered the top-down hierarchies widely present in medical institutions. Psychiatrist George L. Engel6 highlights the lack of room for the social, psychological and behavioural dimensions of illness in the biomedical model, while proposing the biopsychosocial model which builds upon the idea that illness is the result of biological, psychological and social factors. To arrive at a treatment without accounting for the patient’s social context and healthcare systems is insufficient.

The biomedical model reduces mental illness to a brain disease, while placing a strong emphasis on pharmacological treatment and disease-specific drugs, with the ultimate focus being on cure and symptom reduction.

The onus of our mental health cannot only be on us entirely, or deferred to chemicals in our brains, especially when we’re living in a world where there is deep daily inequity and discrimination based on age, body, caste, class, disability, gender, sexuality and religion. While medication is an important part of the treatment plan for many people struggling with their mental health, it can’t be the entire plan. It was not enough for me to have access to some medication and a therapist to give me homework. Though unfortunately, even these incomplete measures remain inaccessible to most Indians today. A government supported national mental health study7 in 2019 stated that among the 150 million Indians in need of mental health services, fewer than one in ten with common illnesses, and only 40- 50% of those with serious mental illnesses are receiving any form of care. And while it is important to ensure we have free and accessible healthcare for all, our vision for mental healthcare needs to go beyond hospitals. The overhaul of the current system involves actively funding alternative treatments, and prioritizing de-institutionalisation, where we seek to imagine a world beyond forced medication, locking people in psychiatric wards, and police restraint. Lawyer Amba Salekar suggests8 well researched models such as: the Soteria paradigm, advocating for recovery through community-service; Open Dialogue, which brings a person together with their family, friends and professionals to discuss the mental health crisis; and projects like the Mental Health Innovation Network: a global community of innovators collecting evidence-based initiatives. While The Mental Healthcare Act, 2017 emphasizes the right to community living, discusses community health centres and establishments, its implementation is still a lacuna where only 1.3% of health expenditure in India is set aside for mental health, and largely concentrated on upgrading tertiary care and state mental hospitals.9

Sinking into the realization of years of childhood sexual abuse, and sitting with it in the aftermath of denial is a painful, lonely, and scary spiral filled with intense self-loathing. At that moment, what I needed most was community care. I needed a space where my pain could be witnessed and held. I needed to be reminded that the shame of experiencing sexual abuse was not mine to hold. I needed a realistic path for my mother to leave her abusive marriage without being ostracized for being a divorcee. I needed housing that wasn’t contingent on having ‘a man in the house’. I needed to not have to choose between having meals for the rest of the month or paying a psychiatrist.

I did not know this as a teenager, so all my discomfort was directed towards what I had then identified as the only controllable source for all this chaos: my body. While my body was already feeling uncontrollable and unruly with shame, I was also developing increasingly frequent migraines, along with daily brain fog, and widespread excruciating body pain. I had tried every single pain medication the doctors had given me, but nothing worked. I barely understood what was happening so when the doctors told me it was my fault, I believed them. Women’s pain has been known across time to have been dismissed by healthcare professionals, and attributed to hysteria. The history of hysteria10 diagnoses can be traced back to 1900 BC in ancient Egypt. And while doctors may have finally learned to not label women “hysterical,” they’ve adopted newer terminology reflecting the same approach. In a piece for Monash University, public health researcher Kate Young11 highlights that a few doctors she interviewed categorized their patients as: good patients and difficult patients. The good patients accept doctors’ guidance, and interpretations without challenges, and the difficult ones don’t find relief from treatments and keep returning for help. Difficult patients’ symptoms were attributed to their psyche. I had learned very early on that I was a very difficult patient. I researched my medications, asked too many questions, and repeated my symptoms when doctors ignored them.

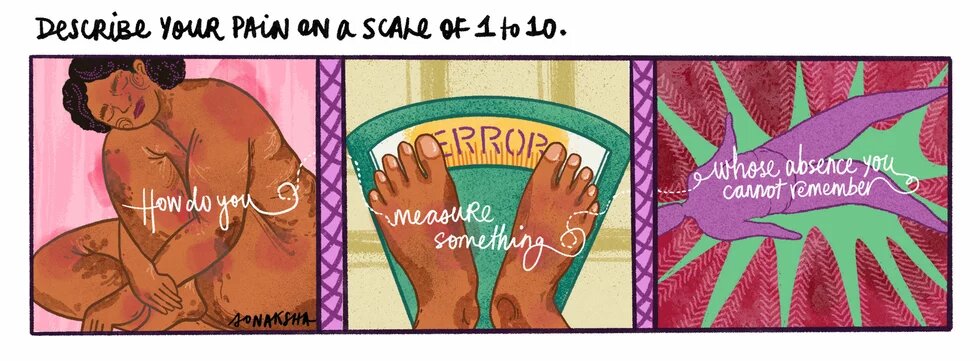

The text across the panels reads: How do you measure something whose absence you cannot remember

Panel 1: Illustration of a person with brown skin hugging their knee and holding their body. Their stretch marks are peeking through and pain points are highlighted with blobs of pink and red.

Panel 2: Illustration of the person standing on a weighing scale with ‘error’ displayed on it.

Panel 3: Illustration of a floating person surrounded by a burst of red.

In addition to being a sick and “difficult patient,” I’m fat. I’ve been fat for most of my life. I can’t remember a time I wasn’t the largest person in the room. Being bullied for my fatness was a reality I had accepted – from peers and family to institutions and workplaces. But some of the most painful anti-fatness I’ve experienced comes from the violence that the medical industrial complex exacerbates against fat people in association with the billion-dollar diet industry. Marquisele Mercedes, a writer and educator working at the intersection of critical public health studies, fat studies and scholarship on racism, writes in a piece for Pipe Wrench Mag12, “Medical fatphobia refers to the specific ways that hatred and denigration of fatness manifest within medicine and the fields that medicine influences, like public health.” Fat people frequently say13 that their bodies invoke hypervisibility, and take on a more active role in healthcare encounters than their thinner peers. Our fatness always becomes the diagnosis, regardless of the symptoms.

Research14 has found that not only are we deemed lazy, undisciplined and weak-willed, but healthcare providers also have shorter appointments with us. So, it wasn’t surprising that the repeated prescription I received for both being constantly depersonalized, and my increasingly disruptive chronic pain, was to lose weight. There was a time in school that I almost completely stopped eating and told everyone I was on a diet. I would dance for hours trying to sweat every kilogram off. I would portion my food to eat just enough to avoid suspicion. But I should never have worried, because everyone around me was ecstatic when I lost over 20 kgs in a month. It was the most love, adoration and praise I have received from my relatives till date. Amidst the joy of my sudden thinness, it went completely unnoticed that I had developed an eating disorder. Delays to, or the denial of, eating disorder diagnoses for fat patients is a shared experience. Even just a few years ago, a doctor told me I was “too fat” to have an eating disorder.

"The weight of disclosure is familiar to those with chronic pain, and other invisible illnesses—not only in our personal lives, but also at the workplace."

Mercedes explains: “For those in the sciences and medicine, the conclusion that fatness is corrupt and corrupting is foregone, discouraging critical thinking about how the scientific consciousness links fatness to death or disease, to the detriment of fat patients. It is rare to find someone in these spaces who has taken any amount of time to question what they know about fatness, how they came to know it, and, more importantly, the consequences of how they treat fat people because of it.” You cannot provide care for fat people when you so deeply hate us for existing in our bodies. You cannot provide care for fat people when you cannot imagine a world where we don’t want to change our bodies. You cannot provide care for fat people when your only desire for us is to fix us. It was hard to imagine how I could begin to feel safe, in my body, and then find love for it or feel pleasure, when the world repeatedly told me that my body was not only wrong, but also undeserving of respect, care and love.

I had my first non-celebrity crush at 19. However, a few months before it happened, I spent a lot of time agonizing over why I had never had a crush. My friends spoke about their crushes from high school, and some as young as kindergarten, so I was certain something was wrong with me. Even WebMD had no answers. It’s not a stretch to say that Mia Thermopolis’s diaries15 and long monologues about her crushes shaped my entire personality as a teen. I’d spent all my life dreaming of fairy tales and romances, so why had I never experienced the intense woozy headrush from a crush for anyone that wasn’t Shah Rukh Khan, or Rihanna. When I actually experienced my first real life crush, I knew that it was because I grew up believing that I wasn’t deserving of romantic love. I had a compendium full of dream romances and dates, but they never featured my body. It’s not hard to believe this because the world constantly reminds us that we’re only worthy of love when we’re healthy and thin. In school, the only time I was crushed on was as a prank. The only ways I was touched were without my consent, like that time a boy ran his hand up my leg and reminded me I should thank him for even liking me. I never saw anyone around me truly desiring or respecting a fat person. Sick people were called unsexy and abandoned by their partners for being a burden. So how could I, as a fat and sick teen, imagine that I could experience romance? I would have to shelve these dreams for my ‘after’ image: the one where I’m not fat or sick anymore.

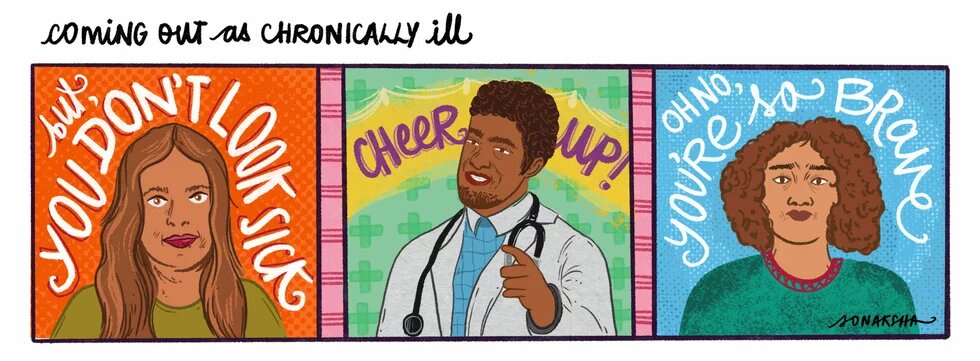

Panel 1: Illustration of a woman with brown hair and light skin with a glassy gaze. The hand-lettered text says: “but, you don’t look sick”

Panel 2: Illustration of a doctor looking cheery with the hand-lettered text “cheer up!”

Panel 3: Illustration of a person with curly brown hair looking concerned and sad. The hand-lettered text says: “Oh no, you’re so brave.”

For the last decade, I’ve spent most of my days being in pain. There are no medications, no illuminating blood tests, so I just have to find ways to get through it. It’s difficult finding hope and desire for anything but numbness when you’re in excruciating pain for the majority of your time awake. I lost friendships, distanced myself from people who knew the most productive version of me, rarely slept, and then reoriented my dreams and life to fit with the body I live in. Most of my friends were dating, getting in and out of relationships, switching jobs, pursuing masters’ degrees – the things we’re expected to do in our early twenties. I wasn’t sure how to explain to myself, let alone anyone else – that I had to spend most of my day tethered to an electric heating pad, cushion each day with at least two short naps, and plan social engagements with week-long breaks between them. The few times I had tried to explain my new life to friends, they began tiptoeing around me, making decisions on my behalf (out of care), or going completely silent. There were either intrusive questions about intimate medical information, or complete hesitation to know more. This weight of disclosure is familiar to those with chronic pain, and other invisible illnesses not only in our personal lives, but also at the workplace. Participation at workplaces stands at 36% for disabled people16 in India, compared to 60% for those without disabilities. And while the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act 2016, promotes inclusion of disabled people across all walks of life, the reality is far from ideal. Most workplaces are severely under-equipped and unable to handle the requirements of creating comprehensively inclusive spaces that go beyond checking boxes on a list.

The Act defines a disabled person as any person “with long term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairment which, in interaction with barriers, hinders his full and effective participation in society equally with others,” which sounds inclusive, but is not enough, because our systems and culture are steeped in ableism. My decision to build my own business was largely influenced by the lack of accommodations in most workplaces I interviewed at. The few times I mentioned chronic pain or fatigue, I received surprised glances and pitying remarks. Other times there was an added emphasis on “working beyond office hours for urgent deadlines” or “the requirement of a doctor’s note for sick leave,” to serve as a deterrent from pursuing these opportunities further. The burden of proof always circles back to us. A common experience for many people with chronic pain is the constant demand of evidence for our suffering, including from healthcare professionals who often don’t acknowledge the intensity of our pain.17 If it’s not visible on a blood test or an x-ray, then it can’t possibly exist, right? But this is not surprising as doctors are hardly equipped to deal with the complexities of chronic pain, given that pain and pain management are not taught in medical schools in 80% of the world.18

Unlike rights, which can be granted and taken away, justice is rooted in our wholeness and integrity.

In a world so rife with ableism and anti-fatness, it feels like a miracle to have allowed myself to experience powerful moments of desire, connection and pleasure. In between hospital visits, and while waiting for a chronic pain diagnosis, I stumbled into my queerness, and almost concurrently found the articulation of disability justice. The first time I fell in love with a woman, was also the first time I brought my heating pad to a first date, was also the first time I experienced someone looking at my body with desire and excitement. It was also when I found my first queer crip19 community: where our chats were filled equally with screaming about the new gay pop song, as with reminding each other to sleep enough, sending care packages stacked with delicious treats, and crying about doctor’s appointments.

It was in these circles of care that I learned the difference between being descriptively disabled and politically disabled20 and it expanded my politics in ways I had never imagined possible. In the words of Mia Mingus, “descriptively disabled people are just anybody who is disabled, but they may not understand themselves in a political way. And being politically disabled is really about folks who have an analysis about ableism, who feel a solidarity with other disabled people who understand their disabled experience as having political meaning and value and weight.” Most people are scared of sickness, they don’t want to think about it because it is adjacent to contending with our mortality. But thinking about sickness and disability is crucial, because it also means acknowledging that we need to be interdependent, it is learning to care for each other, it is realizing that the independence we were achingly chasing is capitalism’s desire, not ours. The truth is, we will all be sick, and we will all be disabled.

There is a loneliness to being fat, and disabled. Ableism counts on isolation and works in insidious ways to erase us from the future, even in the versions of our own dreams for it. We’re told to dream of thin, healthy and able-bodied versions of ourselves. Like many other disabled people, I spend a lot of time dreaming and creating ways to transcend these confines of ableism. As Patty Berne, co-founder of Sins Invalid says, “Because the world continues to treat us as worthless, creating new worlds is a matter of survival for us.” Disability justice is a way to create the just worlds we dream of, with an understanding of the way the different power hierarchies we live within are interlinked: white supremacy, patriarchy, capitalism, ableism, casteism, among others. And unlike rights, which can be granted and taken away, justice is rooted in our wholeness and integrity. Berne says, “Justice is about how we live and love and practice every day interactions.”21

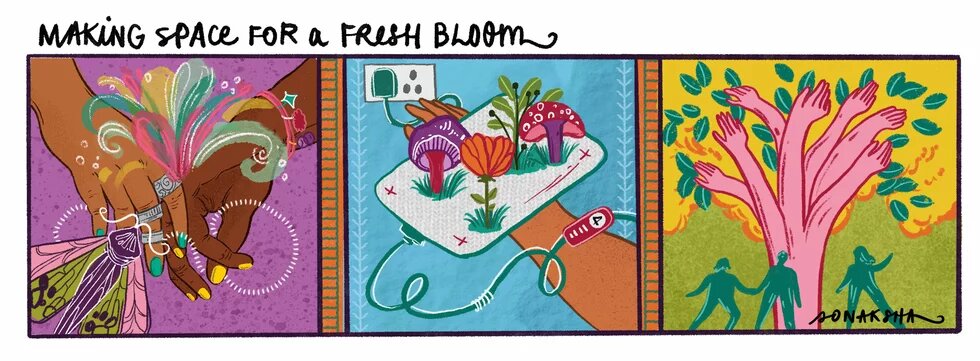

Panel 1: Illustration of two people intertwining hands with a burst of colour and stars erupting from it. A butterfly flies towards the hands.

Panel 2: Illustration of an electric heating pad on a hand with mushrooms and flowers growing out of it.

Panel 3: Illustration of many hands creating the bark of a flowering tree and people gathering below it.

Finding disability justice, experiencing sapphic love and queer crip friendship brought me back to my body. I am learning to show up fully, guided by curiosity, and without shame. In the face of widespread apathy, stumbling into disability justice reminded me that care is more than just turning up at each other’s homes with meals, or thinking about access needs. It is also organizing for the survival of our communities. It is holding institutions accountable for structural and systemic violence against oppressed people. It is the leadership of those who are most affected by historic oppressions. It is seeing and valuing people for who they are, and not how much they produce. And when we dream of liberation, it must also include our planet.

I was once a little child standing in front of the mirror, wondering how I could shrink myself to a dot. I wanted nothing more urgently than to vanish. If they cannot see me, maybe they won’t harm me? If I’m not too much, maybe I’ll be enough? I tethered myself to dreams because my body didn’t feel safe enough, and it was the only way to keep surviving. I’m still dreaming, but now, about what it would be like to finally give my body a chance to sink and expand into softness, after decades of shrinking. I’ve been traversing what it looks like to float in the midst of joy, sadness, anger and grief with openness and lightness. Because making space for queerness and disability to bloom within me, unfurled a path to the home I’m building in my body, and the world. It has become difficult to go on dates or make as many friends as before, but only because I refuse to retreat from these dreams. I believe it is only a matter of time before we bring the world into our magical fold.

Disclaimer:

This article was prepared with the support of the Heinrich Böll Stiftung. The views and analysis contained in the publication are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the foundation. Heinrich Böll Stiftung will be excluded from any liability claims against copyright breaches, graphics, photographs/images, sound document and texts used in this publication. The author is solely responsible for the correctness, completeness and for the quality of information provided.

Footnotes

- 1

The Interplay Between Childhood Sexual Abuse, Self-Concept Clarity, and Dissociation: A Resilience-Based Perspective: Lassri, D., Bregman-Hai, N., Soffer-Dudek, N., & Shahar, G., 2023: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/08862605221101182

- 2

https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/2249/1/A2017-10.pdf

- 3

There has been an increase in using mindfulness as a therapeutic approach in the last decade. Mindfulness at its core is the idea of paying attention, with intentionality, curiosity and compassion. When used in therapeutic settings, the emphasis is on paying attention inwards to emotions, feelings and thoughts, often guided by a body scan.

- 4

The biomedical model of mental disorder: A critical analysis of its validity, utility, and effects on psychotherapy research - Brett J. Deacon, 2013: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0272735813000482?via%3Dihub

- 5

On the term body-mind: https://stimpunks.org/glossary/bodymind/

- 6

The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine – G L Engel, 1977: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/847460/

- 7

National Strategy for Inclusive and Community Based Living for Persons with Mental Health Issues, The Hans Foundation, 2019: https://thehansfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/THF-National-Mental-Health-Report-Final.pdf

- 8

How the Celebrated Mental Healthcare Act Restricts Individual Liberty and Fails to Comply with International Standards – Amba Salekar, 2017: https://caravanmagazine.in/vantage/mental-healthcare-act-restricts-individual-liberty-fails-international-standards

- 9

National Strategy for Inclusive and Community Based Living for Persons with Mental Health Issues, The Hans Foundation, 2019: https://thehansfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/THF-National-Mental-Health-Report-Final.pdf

- 10

Women and hysteria in the history of mental health - Tasca C, Rapetti M, Carta MG, Fadda B, 2012: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3480686/

- 11

Endometriosis, improving women’s care and the ‘hysteria myth’ – Kate Young https://lens.monash.edu/@medicine-health/2019/06/18/1368309/endometriosis-womens-health-and-the-hysteria-myth

- 12

No Health, No Care – Marquisele Mercedes: https://pipewrenchmag.com/dismantling-medical-fatphobia/

- 13

"Whatever I said didn't register with her": medical fatphobia and interactional and relational disconnect in healthcare encounters: Kost C, Jamie K, Mohr E., 2024: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10996856/

- 14

Impact of weight bias and stigma on quality of care and outcomes for patients with obesity: Phelan SM, Burgess DJ, Yeazel MW, Hellerstedt WL, Griffin JM, van Ryn M, 2015: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4381543/

- 15

Mia Thermopolis is the protagonist of the widely popular series ‘The Princess Diaries’ by Meg Cabot. Ref: https://theprincessdiariesbooks.fandom.com/wiki/Mia_Thermopolis

- 16

As a disabled person, I find it affirming to use identity first language while talking about disability, which is also grounded in disability justice. However, some disabled people also use person first language, such as person with disabilities. This has received criticism from some communities who felt it implied shame. However, it’s best to ask the person being referred to what feels most affirming to them, or to use them interchangeably.

- 17

Treating Chronic Pain as Invisible Disability: S Mahalakshmi, Shubha Ranganathan, 2024: https://www.epw.in/journal/2024/22/commentary/treating-chronic-pain-invisible-disability.html

- 18

Pain is the silent epidemic that India's health systems are failing to handle: Kanika Sharma, 2017: https://scroll.in/pulse/829320/pain-is-the-silent-epidemic-that-indias-health-systems-are-failing-to-handle Ref: Judy Foreman, A Nation in Pain: Healing Our Biggest Health Problem

- 19

On the term crip: In naming, I follow the legacy of other disabled people who have chosen the term as a way to reclaim pride in disability as a part of one’s identity.

- 20

Disability Visibility Project: Mia Mingus, Part 1, 2015: https://disabilityvisibilityproject.com/2014/09/25/disability-visibility-project-mia-mingus-alice-wong/

- 21

DVP Interview: Patty Berne and Alice Wong, 2015: https://disabilityvisibilityproject.com/2015/12/14/dvp-interview-patty-berne-and-alice-wong/